NEXT STORY

What makes a good collaboration?

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

What makes a good collaboration?

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21. I’d never thought I was anything very special | 1392 | 00:49 | |

| 22. Luck in science | 1273 | 00:34 | |

| 23. Influences | 1289 | 01:41 | |

| 24. Giving advice to young scientists | 1707 | 01:23 | |

| 25. A career in science starts with an apprenticeship | 2 | 1201 | 01:45 |

| 26. I was fortunate with funding | 1059 | 02:30 | |

| 27. What makes a good collaboration? | 1139 | 02:16 | |

| 28. Theoretical vs experimental biology | 1134 | 03:26 | |

| 29. The effect of World War II on my career | 1217 | 01:11 | |

| 30. What you gossip about is what you’re interested in | 1128 | 01:02 |

One… one of the… the things, fortunately, I’ve never had to do, is a question of… of raising money because when I… I started after the war there was more money around and anyway it was… it was the business of… more of the people one stage above me, the more senior people to get… get money. Science was… expanding, we were supported by the Medical Research Council and for a number of years money wasn’t a serious limitation. Then, of course, there was a period came when money was very tight, but by that time I was no longer doing experimental work. I didn’t need as much money therefore, on the other hand. And… and then it was easier because by then I got sufficient reputation to get money in much more comfortable ways like having an endowed chair as I… I have here at the Salk Institute [for Biological Studies]. So, I haven’t had that but I’ve seen younger people… this is a very severe stress in that they can sometimes can only get money for three years, they have to… and so they have to choose something that’s going to result… produce results within the next… the three years that's coming and before that’s finished they’ve got to start to write another grant request. Sometimes now it goes for five years or say for seven, so money was more serious. On the other aspects, of learning how to do research, yes, I certainly had to learn that and I didn’t at first, I mean, when I started really on my… more on my own, but I did learn from watching [William Lawrence] Bragg and some of my other colleagues. But I think one of the other things which I haven’t mentioned that you learn is… is when you have fairly close friends and to discuss things with them. And this is really, for most people, there are few people who work best in the solitary way, but for most people and certainly for… for scientists, I wouldn’t like to say for mathematicians, certainly for scientists it… it helps to have one or two close friends with whom you continually talk about things because… and often you can talk an enormous amount. This is what I did with Jim Watson, and this is what I did later with Sydney Brenner and also with this mathematical friend of mine Georg Kreisel, for example; all these ones help you to see how to go about problems and prevent you get… stuck… stuck in a rut, so that it’s really part of your education talking to your contemporaries as well as having the apprenticeship with older people.

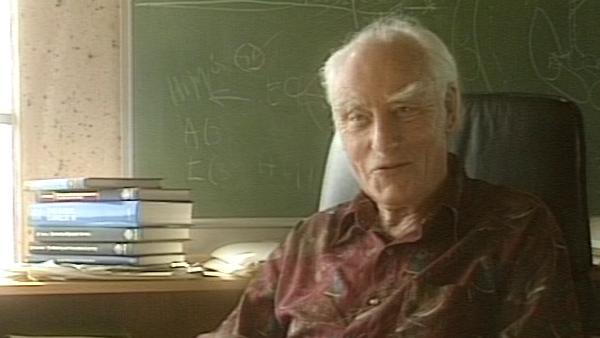

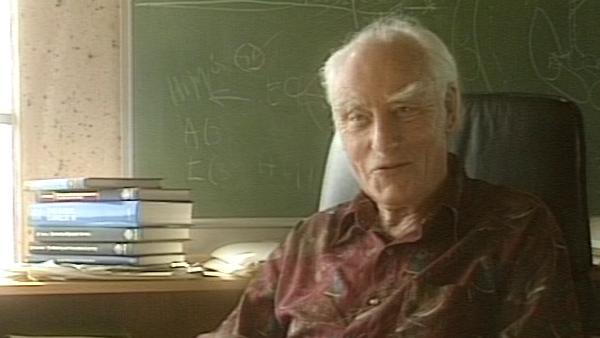

The late Francis Crick, one of Britain's most famous scientists, won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. He is best known for his discovery, jointly with James Watson and Maurice Wilkins, of the double helix structure of DNA, though he also made important contributions in understanding the genetic code and was exploring the basis of consciousness in the years leading up to his death in 2004.

Title: I was fortunate with funding

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: World War II, Medical Research Council, Salk Institute for Biological Studies, William Lawrence Bragg, James Watson, Sydney Brenner, Georg Kreisel

Duration: 2 minutes, 30 seconds

Date story recorded: 1993

Date story went live: 24 January 2008