NEXT STORY

The road to Cambridge

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The road to Cambridge

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 31. The two areas of biology I chose to work in | 859 | 01:57 | |

| 32. Social interactions among scientists | 950 | 03:06 | |

| 33. Molecular biology in the late 1940s | 1202 | 03:08 | |

| 34. The road to Cambridge | 1245 | 02:16 | |

| 35. James Watson - the bald American | 2101 | 01:25 | |

| 36. James Watson - precocious and fun | 1754 | 01:51 | |

| 37. Treating our research results with caution | 1261 | 00:55 | |

| 38. The triplet code | 1 | 1288 | 00:44 |

| 39. The difficulties solving scientific problems | 1277 | 01:06 | |

| 40. The emotional ups and downs of scientific research | 1382 | 01:10 |

Well, molecular biology, as we would call it now, in the late ’40s was in a very confused state. It’s very difficult, especially for young people now, to realise that all the things they take for granted, we didn’t know then. We… we didn’t know what genes were made of, that was one of the main problems. We certainly didn’t know how they replicated. It was almost impossible to see how a gene might be replicated. And we certainly didn’t know how a gene act, although by that time there was evidence to suggest that a gene might be important for coding for a protein… protein. ‘One gene, one enzyme’ was the slogan at the time. There was experimental evidence that suggested that DNA might have some part in the genetic material, produced by… this evidence by [Oswald] Avery, [Colin] MacLeod and [Maclyn] McCarty, but the general feeling was that genes were made of protein because proteins were more sophisticated molecules, and that’s what probably you wanted for a gene. So the thing was in a very confused state, and that of course is partly what Jim [Watson] and I talked about a lot of the time. Was it… was it DNA? Was it protein? What could the structure of DNA be? And we were aware, of course, of the work going on in King’s College London, the experimental work trying to discover from the fibres of DNA what the structure was. And we followed that reasonably closely, especially as I was friendly with Maurice Wilkins. But nevertheless, it was very strange, and even up to a few days before we first saw the idea of the structure, we were in a state of pretty total confusion. So, it happened very suddenly when Jim got the idea of the base pairing, and we also knew the chains ran in opposite directions – we’d deduced that from Rosalind Franklin’s data – and… and that we could build a model. We had to show that a model could be built, it wasn’t just a bright idea. And once we had a… a model that looked really very convincing, of course, and then we… we told the people in London about it, and they told us where they had got, which was quite a way in that direction, and compared the thing. So it suddenly looked very promising. The whole world suddenly changed. We could see the outline. We could see outlined possible answers to all the questions we’d been asking, although we didn’t know, of course, if the answers were true, and all the details had to be worked out. So that’s why, from that period, we could make shrewd estimates as to what it was that was likely to be discovered and – with the reservations that we didn't get it very accurately – how long it would take. I don’t think any of us thought that it would come out quite so quickly. Certainly we didn’t before the DNA structure. And there is a certain similarity now, if you work on the brain, where it’s in the same confused state that molecular biology was in the pre-DNA period, I would say. But whether that’s a useful analogy, only time will tell.

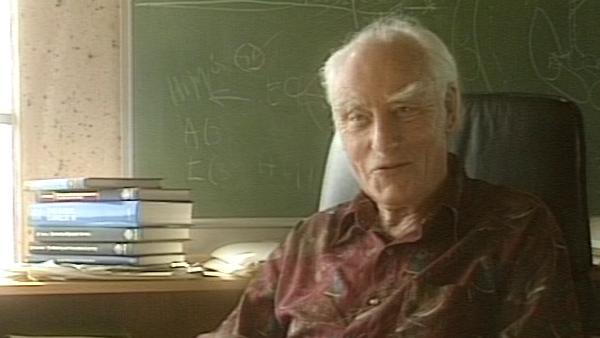

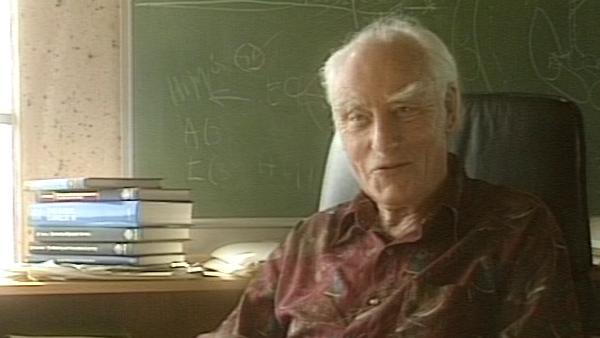

The late Francis Crick, one of Britain's most famous scientists, won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. He is best known for his discovery, jointly with James Watson and Maurice Wilkins, of the double helix structure of DNA, though he also made important contributions in understanding the genetic code and was exploring the basis of consciousness in the years leading up to his death in 2004.

Title: Molecular biology in the late 1940s

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: King’s College London, London, Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod, Maclyn McCarty, James Watson, Maurice Wilkins, Rosalind Franklin

Duration: 3 minutes, 8 seconds

Date story recorded: 1993

Date story went live: 24 January 2008