NEXT STORY

Alex Novikoff

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Alex Novikoff

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 51. The first lysosomal storage disease | 126 | 04:29 | |

| 52. Dame Honor B Fell and vitamin A | 79 | 03:49 | |

| 53. 'Pericanalicular dense bodies' | 99 | 02:55 | |

| 54. Alex Novikoff | 196 | 05:25 | |

| 55. Uricase: Not a typical enzyme | 109 | 02:31 | |

| 56. Peroxisomes | 1 | 162 | 05:20 |

| 57. Becoming weary of teaching and administrative duties | 131 | 03:59 | |

| 58. Joining the Rockefeller Institute | 100 | 02:59 | |

| 59. A dual life between New York and Louvain | 121 | 04:01 | |

| 60. Jacques Berthet and Miklós Müller | 169 | 05:16 |

I happen to be very much of a biochemist by training and I'm a very poor morphologist. I had considerable trouble when I was a medical student in remembering things like anatomy and microscopy, histology and pathology. I could not recognise anything in a cell, in a microscope; I could only see the red blood cells in my own retina. So I've never used my eyes very much for studying and so – I of course didn't mention this, I'm glad you asked – when we had characterised the lysosomes, eventually, as a good biochemist would do with a molecule, having characterised them, we devised techniques for purifying them and so, eventually, we... we were able to make highly purified preparations of lysosomes the way a biochemist would get a crystal in protein... the same kind of thing. And then, eventually, we went and looked at them in the electron microscope because, by then, I had amazingly been able to receive from the Belgian National Science Foundation what was about the first electron microscope that they had given, and all my morphological colleagues were livid with rage that the electron microscope should be given to a biochemist and not to a morphologist. Anyway, tout ça c'est de l'histoire ancienne. Anyway, we did finally look in the electron microscope, and we found that these little bodies that we had called lysosomes had been seen by electron microscopists who had called them pericanalicular dense bodies. Dense because they look dense, because they're filled with undigested residues – that's why they're dense, because, even in normal cells, sometimes you get residue that cannot be digested. And pericanalicular because they are around bile canaliculi in the cells, so we ended up doing a lot of morphological work and many of my co-workers did cytochemistry, immunochemistry, radiochemistry, you name it, they did it, but I was never much involved in that because the morphological techniques were not really my... my cup of tea.

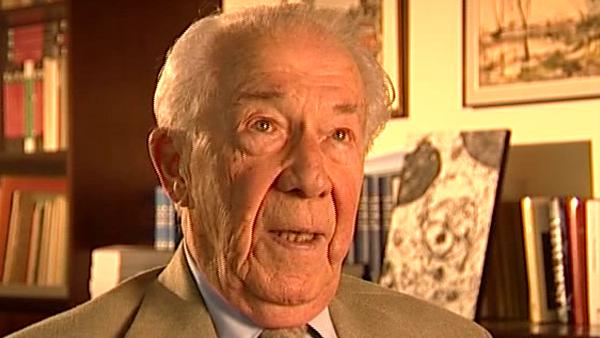

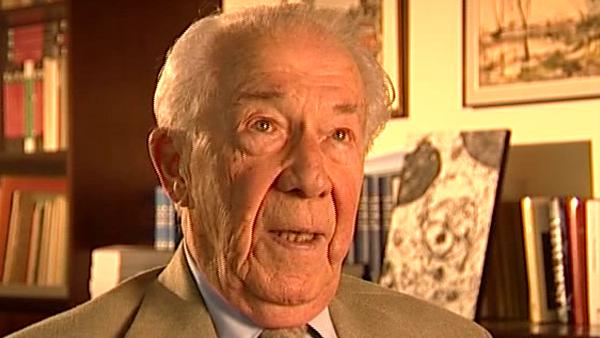

Belgian biochemist Christian de Duve (1917-2013) was best known for his work on understanding and categorising subcellular organelles. He won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1974 for his joint discovery of lysosomes, the subcellular organelles that digest macromolecules and deal with ingested bacteria.

Title: 'Pericanalicular dense bodies'

Listeners: Peter Newmark

Peter Newmark has recently retired as Editorial Director of BioMed Central Ltd, the Open Access journal publisher. He obtained a D. Phil. from Oxford University and was originally a research biochemist at St Bartholomew's Hospital Medical School in London, but left research to become Biology Editor and then Deputy Editor of the journal Nature. He then became Managing Director of Current Biology Ltd, where he started a series of Current Opinion journals, and was founding Editor of the journal Current Biology. Subsequently he was Editorial Director for Elsevier Science London, before joining BioMed Central Ltd.

Tags: lysosomes, electron microscope, cells, morphology

Duration: 2 minutes, 55 seconds

Date story recorded: September 2005

Date story went live: 24 January 2008