NEXT STORY

The Quentin Blake Gallery of Illustration

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The Quentin Blake Gallery of Illustration

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 51. An international project led by an Englishman | 82 | 04:43 | |

| 52. An exhibition at the Petit Palais | 84 | 05:39 | |

| 53. The Campaign for Drawing and The Big Draw | 140 | 04:22 | |

| 54. Moving from the museum tunnels to museum walls | 91 | 04:28 | |

| 55. The Quentin Blake Gallery of Illustration | 274 | 05:50 | |

| 56. Gallimard Jeunesse: my French publishers | 113 | 03:13 | |

| 57. Gallimard Jeunesse: publishing a book of French poetry | 112 | 05:12 | |

| 58. Gallimard Jeunesse: Prix littéraire Quentin Blake | 94 | 05:43 | |

| 59. Illustrating The Hunchback of Notre Dame | 159 | 04:41 | |

| 60. Drawing for adults | 140 | 04:52 |

Then we moved on to the museums, to the British Museum, to the Victoria and Albert Museum, to the Natural History Museum, and each year people were invited in, and more and more people came. A couple of years ago it was the Natural History Museum, and I think 14,000 visitors came on that day, to draw, and at the V&A I think we gave them cardboard suitcases to put their drawings in, and… I've been involved in doing the sort of logos and drawings and things like that, and talks, alongside everybody else, for these occasions. It… the idea of it I think, is that people should be… should be allowed to draw if they want to. Everybody draws to begin with. You… you… have… when you start out, I think you're learning a verbal language and a visual language at the same time, and they're more easily kind of related to each other. The… as the verbal language triumphs, the visual one fades, and you become inhibited, and you don't want to do it, and you don't want to show that you don't do it as well as other people. And it's an attempt to give that value. I think people do respond to it. I mean they obviously do respond to it, the number of people come to take part… both children and adults, and I remember going to such an event at the National Gallery of Wales, in Cardiff, where I'd suggested that they should get people of my generation to draw, because they would be able to draw things from 50 years ago, that young people perhaps wouldn't know about. And I went down there, and I think I was supposed to go at two o'clock to exhort these people to draw, who'd come into the museum, and, I remember getting there at two o'clock, and there were about 40 or 50 of them already. They'd all been there for an hour or more, and they'd said, 'Why do we have to wait for him? Can we start straight away?' So everybody… we had to stop them drawing, so that I could encourage them to draw. But I didn't… I mean I tried not to take too long over it. The other thing that was interesting about it was… I mean now there are 1,000 such occasions in the… in the campaign in October, but the other thing that I found particularly interesting about it was that it actually changed people's relationship with the museum. That was something which I hadn't expected to see. I mean I knew I was interested in drawing, and I you know, and I thought people ought to be able to draw if they wanted to, but… it meant they were going into the museums with a… with a purpose, which they didn't have otherwise. I mean previously, lots of people go into museums with no inhibitions at all, but some don't quite know why they're going there, or if they go, they feel that these works belong to someone else and that they are allowed to look at them. If you go in there to draw them, you… or to take in some other activity that goes along with drawing, you know why you're there, I think, and certainly, I mean… with those people in… also with those… with those people in Cardiff at the National Gallery of Wales, a lot of people said, 'I haven't been in this building for 40 years'. And they'd come to do that, and they were obviously, you know, interested in what was happening, and the focus, which you can see people giving to something as they draw it, they're looking at it in a way that they would not previously have done. They have a very real relationship to it, as they are drawing it. They have to concentrate on it in a way that most people probably wouldn't do if they went into a gallery of their own volition, they don't look at it in quite that focused sort of way. So that's another way that it seems to have spread out beyond the books. But one hopes that it means that people will actually not only go on drawing themselves, but take more interest in drawing, and being able to see it as not necessarily just a preparation for a painting or a preparation for something else, but as something interesting in itself.

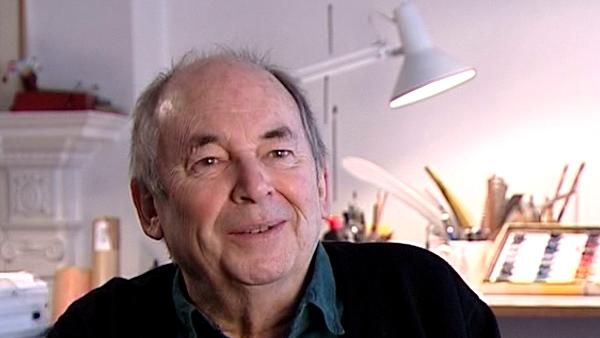

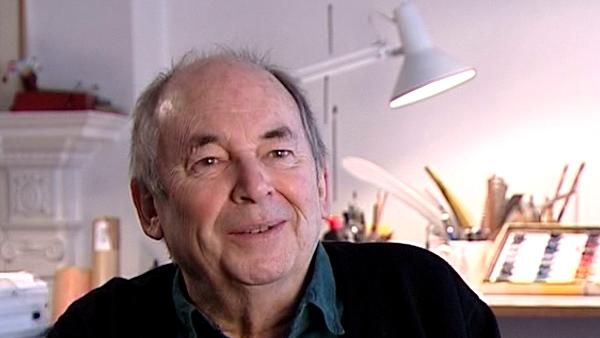

Quentin Blake, well loved British writer and illustrator, is perhaps best known for bringing Roald Dahl's characters to life with his vibrant illustrations, and for becoming the first ever UK Children's Laureate. He has also written and illustrated his own books including Mr Magnolia which won the Kate Greenaway Medal.

Title: Moving from the museum tunnels to museum walls

Listeners: Ghislaine Kenyon

Ghislaine Kenyon is a freelance arts education consultant. She previously worked in gallery education including as Head of Learning at the Joint Education Department at Somerset House and Deputy Head of Education at the National Gallery’s Education Department. As well as directing the programme for schools there, she curated exhibitions such as the highly successful Tell Me a Picture with Quentin Blake, with whom she also co-curated an exhibition at the Petit Palais in Paris in 2005. At the National Gallery she was responsible for many initiatives such as Take Art, a programme working with 14 London hospitals, and the national Take One Picture scheme with primary schools. She has also put on several series of exhibition-related concerts. Ghislaine writes, broadcasts and lectures on the arts, arts education and the movement for arts in health. She is also a Board Member of the Museum of Illustration, the Handel House Museum and the Britten-Pears Foundation.

Tags: British Museum, Victoria and Albert Museum, Natural History Museum, National Gallery of Wales, Cardiff

Duration: 4 minutes, 29 seconds

Date story recorded: January 2006

Date story went live: 24 January 2008