NEXT STORY

Memory

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Memory

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Why I tell jokes | 2 | 699 | 01:53 |

| 2. Early memories and my father | 172 | 04:07 | |

| 3. My mother and school | 131 | 01:13 | |

| 4. My grandparents and visiting their old house | 1 | 118 | 03:58 |

| 5. King Alfred School | 131 | 03:49 | |

| 6. Creativity and the influence your parents have on you | 148 | 03.00 | |

| 7. Joining the RAF and investigating mediums in Blackpool | 140 | 04:41 | |

| 8. Why I was interested in mediums and my investigations in Blackpool | 123 | 05:12 | |

| 9. My time in Canada with the RAF | 119 | 03:17 | |

| 10. Cambridge and meeting Bertrand Russell | 317 | 05:12 |

I went to Cambridge. I actually got a scholarship from the RAF and I went to my father’s college, Downing, and I did philosophy and experimental psychology, two years of philosophy, and I was very, very fortunate because among my teachers was Bertrand Russell and I met him for an hour every Thursday for a couple of terms in 1948 that was. I went up in 1947.

And that was wonderful. It was in a lovely room in Trinity and he would sit on this sofa, smoking a pipe. He had a second pipe which was cooling down so he’d smoke his pipe and pick up the cool one and then smoke that continuously. But instead of talking about logic and inductive influence, which particularly interested me at that time and he’d just written a book on it called Human Knowledge, he was terribly concerned with Berlin and what was going to happen because the Russians had got into Berlin before the Americans, you know. It was a big problem at that time: who was going to run Europe? Who was going to dominate Europe? This was before CDN, of course, he got very involved after that in atomic energy, it was before that, but he was so concerned about this political thing, it’s only really when we talked about Wittgenstein that he’d get interested again and the reason for that, between you and me and the gate post, was that he wanted to be remembered as the great philosopher of the 20th century and he was afraid that Wittgenstein, who of course was his protégée, would pip him at the post and he really wanted us, young men, of no consequence whatsoever except that we had a future - he was 76 by that time so he didn’t have so much future - would accept Wittgenstein as the master instead of him, Bertrand Russell. It was quite interesting, so he really did sort of worse to his views to a great extent, you know.

[Q] Was he impressive?

Well, the thing is, you got... was he impressive? Yeah, he was, but the thing is you got an enormous halo effect with people like that. I mean when you are young and you’ve got somebody like Bertrand Russell, he was 76, you know, he came to Cambridge one day a week at that time. I think he was between marriages or something. He was such a grand man. We looked at his Principia Mathematica, his other books, and I’ve read many of his books actually, and his prose style, his writing, of course, were absolutely wonderful, that one couldn’t but think of him if not as God at least as somebody very close to it, almost not quite mortal, you know, and consequently whenever he said anything, one tended to think there must be the ultimate truth in it, and if one didn’t understand it, one ascribed that to one’s own stupidity not to him making a mistake, you know.

I think the thing, little tiny episode that I remember now vividly because I suppose of arrogance or something, but I had a really rather good conversation with him and I can remember exactly what it was about. It was about Keynes' Theory of Probability and Keynes needed an initial probability to get the thing going so he took it at point five, in other words, that things were equally balanced when there was no evidence whatsoever, and then the mathematics went on from there and I said how can you really justify that? It was obviously something he’d been thinking about because he suddenly woke up and got excited about this and we had a really good conversation about it, and he’d just written this book, Human Knowledge, Its Scope and Limits, which I think is a very, very good book, it’s not one of his most successful books, I think it’s very good, and it’s about scientific methods inductive inference and so on. And there was a pile of them, it had just come out, by his chair, and he took the top one off, signed it and gave it to me, and I was so bucked about it and I still have it with his signature on it, in it. That was really nice. I mean he was such a reputation, he was just outstanding that suddenly to be given a book by him was a wonderful treat, you know. I think these little tiny things, one never forgets actually. It’s one of the great things about going to Cambridge or one of the other great universities, you had amazing visitors, amazing teachers, that one could completely respect, you know. I think this is really important, that universities have people who stand out as amazing in an international sense actually. And then when you get the little silly episode like that, you see, it has tremendous significance. If he was Joe Bloggs, who had the same conversation and then he produced some crummy book or something, it would have meant absolutely nothing and I would not remember it now, 40 years later. As it is, I remember it, 40 years later, vividly. I can see him sitting there.

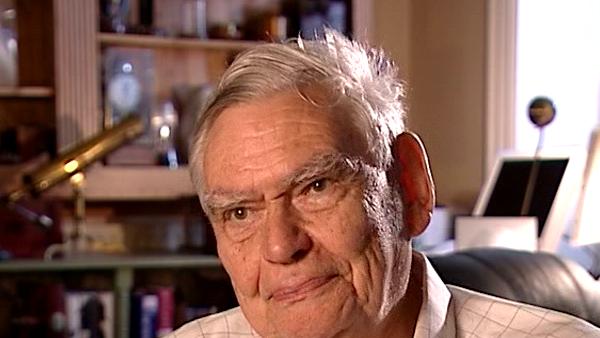

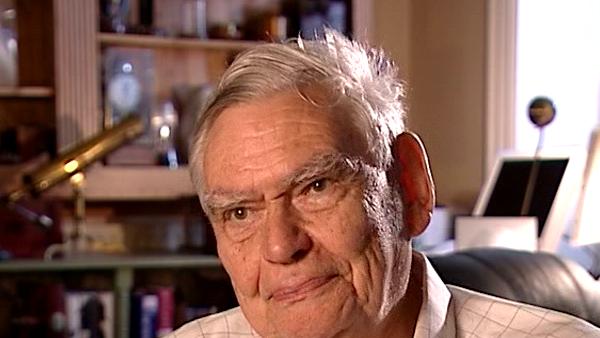

The late British psychologist and Emeritus Professor of Neuropsychology at the University of Bristol, Richard Gregory (1923-2010), is well known for his work on perception, the psychology of seeing and his love of puns. In 1978 he founded The Exploratory, an applied science centre in Bristol – the first of its kind in the UK. He also designed and directed the Special Senses Laboratory at Cambridge which worked on the perceptual problems of astronauts, and published many books including 'The Oxford Companion to the Mind', 'Eye and Brain' and 'Mind in Science'.

Title: Cambridge and meeting Bertrand Russell

Listeners: Adam Hart-Davis Sally Duensing

Born on 4 July 1943, Adam Hart-Davis is a freelance photographer, writer, and broadcaster. He has won various awards for both television and radio. Before presenting, Adam spent 5 years in publishing and 17 years at Yorkshire Television, as researcher and then producer of such series as Scientific Eye and Arthur C Clarke's World of Strange Powers. He has read several books, and written about 25. His latest books are Why does a ball bounce?, Taking the piss, Just another day, and The cosmos: a beginner's guide. He has written numerous newspaper and magazine articles. He is a keen supporter of the charities WaterAid, Practical Action, Sustrans, and the Joliba Trust. A Companion of the Institution of Lighting Engineers, an Honorary Member of the British Toilet Association, an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Photographic Society, the Royal Society of Chemistry, the Society of Dyers and Colourists, and Merton College Oxford, and patron of a dozen charitable organizations, Adam has collected thirteen honorary doctorates, The Horace Hockley Award from the Institute of Scientific and Technical Communicators, a Medal from the Royal Academy of Engineering, the Sir Henry Royce Memorial Medal from the Institute of Incorporated Engineers, and the 1999 Gerald Frewer memorial trophy of the Council of Engineering Designers. He has no car, but three cycles, which he rides slowly but with enthusiasm.

Sally Duensing currently is involved in perception exhibition work and research on science and society dialogue programmes and is working with informal learning research graduate students and post-docs at King's College, London. In 2000 she held the Collier Chair, a one-year invited professorship in the Public Understanding of Science at the University of Bristol, England. Prior to this, for over 20 years she was at the Exploratorium, a highly interactive museum of science, art and perception in San Francisco where she directed a variety of exhibition projects primarily in fields of perception and cognition including a large exhibition on biological, cognitive and cultural aspects of human memory.

Duration: 5 minutes, 12 seconds

Date story recorded: June 2006

Date story went live: 02 June 2008