NEXT STORY

The Apostles society

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The Apostles society

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. The difference between voluntary and involuntary actions | 2 | 417 | 04:41 |

| 12. The Apostles society | 514 | 03:31 | |

| 13. Medical students don't have time for theatre | 421 | 05:57 | |

| 14. Location of the soul | 1 | 381 | 04:38 |

| 15. Death is not an exit | 582 | 02:05 | |

| 16. Darwin didn't change my life | 1 | 607 | 05:27 |

| 17. Exposure to -isms | 339 | 01:31 | |

| 18. The person from Porlock | 305 | 03:54 | |

| 19. Leaving medicine for theatre | 2 | 347 | 06:40 |

| 20. The 'Wizard of Oz' effect: Work for the BBC | 1 | 365 | 05:53 |

I suppose that I was fascinated by what it was that distinguished things like sweating and sneezing and blushing from things like picking up a cup of tea and bringing it to my lips. I would never have surprised myself to find while talking to someone that my arm was involuntarily bringing a cup to my lips, it might’ve been absentmindedly being brought to my lips while I was engaged in talking, but at no point would I have ever said that this was an involuntary action like blushing and sweating or sneezing. So that I became interested in what it was for something to be a voluntary action.

But then… much earlier on I suppose that I had been struck by the difference between actions and events. In other words what is the difference between a piece of soot rolling down a sloping sheet of paper and, as Robert Frost once described in a poem of his called A Considerable Speck, what’s the difference between that and a tiny almost imperceptible speck which by its movements across the page led him to credit it with vitality. And I suppose very early on as a biologist I became preoccupied with what it was for something to be vital and alive as opposed to being inanimate and inert. There was quite clearly a difference between a rock rolling downhill and an ant going uphill and stopping and pausing and suddenly moving at right angles to its transit and going elsewhere and stopping and picking things up.

Well, at a much higher level there is something comparable about us. There are things over which I have no control. Once I have taken food and it’s got to a certain point in the back of my mouth and I voluntarily swallow it, it’s out of my hands, I have no further either concern with, let alone control of, its proceeding down my intestine. That’s an internal affair, though an affair of mine, but it’s an affair of mine over which I, as the proprietor of it, have no control. Whereas the taking of food, the choosing of food, the preparing of food, the hunting for it, in addition to being affairs of mine, they are affairs of mine over which I exercise voluntary control and choice. But I can’t, as it were, halfway down my intestine decide to halt the peristalsis and say, right, stop now, let’s put it off for a while so that I am not embarrassed by wanting to take a shit.

I can make myself vomit but I can’t vomit voluntarily. I can make myself sneeze but I can’t sneeze at will; I can take snuff or stare into the sun and find that I have, to my pleasure, sneezed, but I can’t, as it were, decide to sneeze and do so, though I can make myself sneeze by doing things which bring about the involuntary action of sneezing. So that I became very interested in that and I became very fascinated by that when I went into clinical medicine and went to University College as a clinical student. But by that time, as a result of people like Russ Hanson, as a result also of the neurobiologists who had taught me, Fergus Campbell, for example, who was a visual physiologist at St John’s, I’d got very interested in vision and what, how vision implemented itself.

It was obviously something different from merely having my eyes open. I had to do something in order to see things, though what it was I had to do eluded me. I could decide to look, but in deciding to look I was completely unaware of what it is that I did in order to bring looking about.

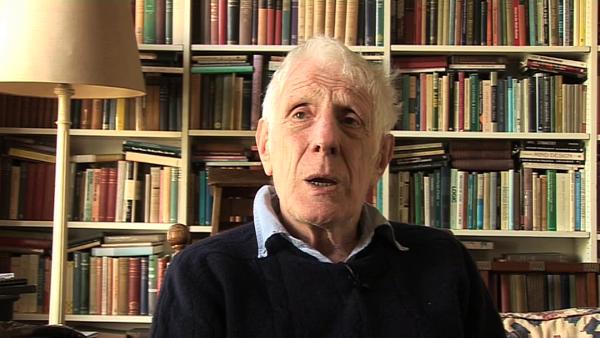

Jonathan Miller (1934-2019) was a British theatre and opera director. Initially studying medicine at Cambridge, Sir Jonathan Miller came to prominence with the production of the British comedy revue, Beyond the Fringe. Following on from this success he embarked on a career in the theatre, directing a 1970 West End production of The Merchant of Venice starring Laurence Olivier. He also started directing opera, famously producing a modern, Mafia-themed version of Rigoletto.

Title: The difference between voluntary and involuntary actions

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: St John's College, Norwood Russell Hanson, Fergus Campbell

Duration: 4 minutes, 42 seconds

Date story recorded: July 2008

Date story went live: 23 December 2008