NEXT STORY

Summing up my career

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Summing up my career

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 81. What scientists want | 89 | 04:42 | |

| 82. Summing up my career | 146 | 03:42 |

It’s a very interesting phenomenon, but I’m sure there are people who are getting profiles of one kind of another, but it’s nothing like that. So you never know what, people... and yet these are the... when you ask people what they wanted, this is what they said they wanted. But when it came, when push came to shove, basic research scientists don’t know what they want. Because somebody said, 'If I knew what I wanted, I would have made the discovery'. It’s sort of, it’s a kind of an interesting conundrum, where you try and supply them with something that, what would be the ideal document, would solve the problem that they’re working on. Well, who wants that? It’s like the, the, we used to talk about, do scientists really want to do literature searches? Effectively, when I used to, when, we used to talk about it this way, I said to a librarian, go into a library, and a guy is saying, do you think the average scientist comes to you, and he’s happy when you come up with, with papers that anticipate his ideas? He’s looking to you, for you to prove that he, that it’s a novel idea, not, not that it’s unoriginal. And it’s the same thing with a patent. What’s the motivation for getting somebody to do a search for, for prior art, when he knows that if he does this search completely right, he won’t get the patent. Right? The last thing I want to know is that it’s not an idea, an original idea. Same thing when people were doing searches on compounds, you know. They weren’t really all that well-motivated. So, you’ve got a kind of... right? So, you’ve got to force them to do it. That’s, that, that’s part of the dilemma that we face in using information for discovery processes, you know. So... you eventually solve it. But people like Josh Lederberg always pointed out later on that if you’re a mature scientist, eventually you get over that. And his talent would be, and people like him, in framing questions for which you give them partial answers. I mean, I’m interested in what people cite – if they cite my work, it’s about citation and indexing work, or it’s about impact factor, or it’s about this, but it’s not necessarily the answer to some fundamental question I’m trying to investigate. If it turns out to be the case, well, great. You know, if you’re working in a field of genetics, of course, if somebody answers some fundamental question, well, that’s what you give people prizes for. But you don’t get upset by the fact that somebody like Jim Watson, you know, identified the double helix; you go on from there and then you go to the next step, right? So, it’s your attitude, being mature about how you use and await discoveries, you know. There’s plenty more to be discovered after the, after your great idea is proven not to be so original anymore. It’s a good idea, but it isn’t original. That’s... that’s what makes science go around. I see that, I was recently asked about a paper that Tibor Braun has got, somebody submitted a paper, I think, about doing an analysis of words that are sound like, new or novel or creative. Irv Sher and I did a study that, years and years ago, how often people use the word 'new'. Every scientist publishes something; he thinks it’s new and novel. And there was a lot of discussion among editor’s list as to whether they should ever even let people use the word 'novel' in a title. Should you have to say it? If it’s novel, that’s why we’re accepting your paper. But some people... a novel method for doing this, or a new compound for doing that. So, I don’t know how much that’s changed or not, but that, that’s what motivates people in one... that priority of discovery is not just for patents.

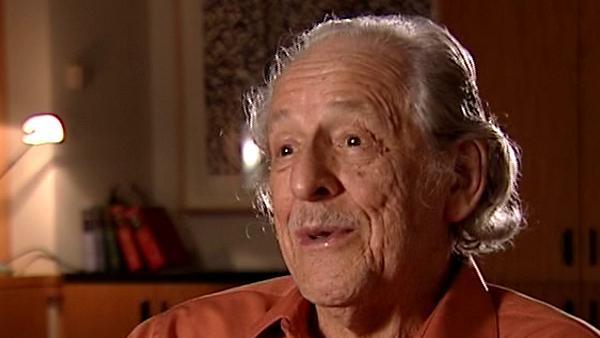

Eugene Garfield (1925-2017) was an American scientist and publisher. In 1960 Garfield set up the Institute for Scientific Information which produced, among many other things, the Science Citation Index and fulfilled his dream of a multidisciplinary citation index. The impact of this is incalculable: without Garfield’s pioneering work, the field of scientometrics would have a very different landscape, and the study of scholarly communication would be considerably poorer.

Title: What scientists want

Listeners: Henry Small

Henry Small is currently serving part-time as a research scientist at Thomson Reuters. He was formerly the director of research services and chief scientist. He received a joint PhD in chemistry and the history of science from the University of Wisconsin. He began his career as a historian of science at the American Institute of Physics' Center for History and Philosophy of Physics where he served as interim director until joining ISI (now Thomson Reuters) in 1972. He has published over 100 papers and book chapters on topics in citation analysis and the mapping of science. Dr Small is a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, an Honorary Fellow of the National Federation of Abstracting and Information Services, and past president of the International Society for Scientometrics and Infometrics. His current research interests include the use of co-citation contexts to understand the nature of inter-disciplinary versus intra-disciplinary science as revealed by science mapping.

Duration: 4 minutes, 42 seconds

Date story recorded: September 2007

Date story went live: 23 June 2009