NEXT STORY

The importance of support for pure science

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The importance of support for pure science

RELATED STORIES

[Q] By the beginning of '45, in fact probably by the end of '44, it was clear that the Allies were going to win the war, even if it wasn't clear what the precise date would be. And people were already beginning to think about what will happen after the war.

We were beginning to think about that, especially after the surrender of Germany in May of '45, and even more after August when Japan also surrendered. It was clear to us, well... that our main interest, at least that of a large fraction of the Los Alamos scientists, was to return to the universities. And so, indeed, we made plans to do so. And I returned in January of '46.

Before we returned, we wanted nuclear physics to be well recognized at the university. So already in... I believe, already in September, Bacher, and I and Parrent, went back to Cornell University and said 'Well, nuclear physics, obviously is very useful. There are lots of things to be done. Scientifically, we would like to have a laboratory specifically devoted to nuclear physics.' The president of the university, Ezra Day, was very receptive, and said 'Yes, of course, we'll do that. We'll give you a laboratory.' And he got authorization by the board of trustees very quickly to have such a laboratory built, which would be under the direction of Robert Bacher. The... fortunately for Cornell University, in the end, the main cost of the laboratory was borne by the Office of Naval Research, the Navy Research Laboratory and... and generally some farsighted naval officers said it is important to have pure science continued, it is important for the government to support pure science, we want to support laboratories at universities which will train pure scientists, so that the country remains strong and becomes even stronger in pure science. And this was very farsighted. They did emphasize pure science, not applied science, not science useful for the Navy, not science useful for the military, but pure science, which gives the real training of the minds of young people.

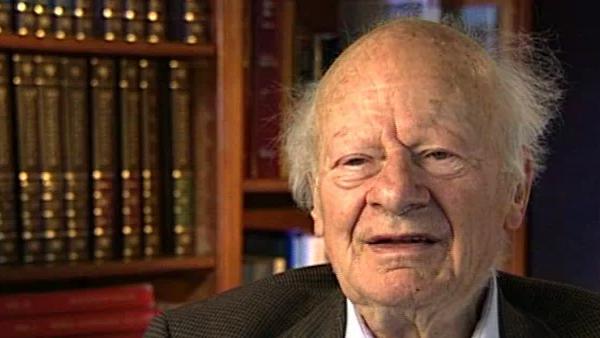

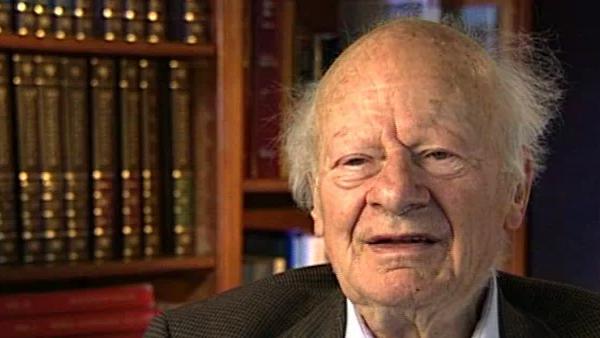

The late German-American physicist Hans Bethe once described himself as the H-bomb's midwife. He left Nazi Germany in 1933, after which he helped develop the first atomic bomb, won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1967 for his contribution to the theory of nuclear reactions, advocated tighter controls over nuclear weapons and campaigned vigorously for the peaceful use of nuclear energy.

Title: The creation of a nuclear physics laboratory at Cornell

Listeners: Sam Schweber

Silvan Sam Schweber is the Koret Professor of the History of Ideas and Professor of Physics at Brandeis University, and a Faculty Associate in the Department of the History of Science at Harvard University. He is the author of a history of the development of quantum electro mechanics, "QED and the men who made it", and has recently completed a biography of Hans Bethe and the history of nuclear weapons development, "In the Shadow of the Bomb: Oppenheimer, Bethe, and the Moral Responsibility of the Scientist" (Princeton University Press, 2000).

Tags: 1944, 1945, Germany, Japan, Nazis, Cornell University, Office of Naval Research, Navy Research Laboratory, Robert Bacher, Ezra Day

Duration: 4 minutes, 5 seconds

Date story recorded: December 1996

Date story went live: 24 January 2008