NEXT STORY

Designing aeroplanes

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Designing aeroplanes

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Early childhood and a passion for natural history | 4 | 4555 | 02:55 |

| 2. Developing a deeper interest in the living world | 1 | 1750 | 00:53 |

| 3. Not fitting in at prep school or Eton | 1 | 1805 | 02:11 |

| 4. Futile Latin lessons at Eton College | 1 | 1707 | 01:08 |

| 5. Studying mathematics and English | 1 | 1882 | 00:55 |

| 6. Reading Haldane's Possible Worlds at Eton | 1 | 1956 | 02:23 |

| 7. The influence of science fiction | 1762 | 01:41 | |

| 8. Announcing my career plans over Sunday lunch | 1361 | 02:54 | |

| 9. Applying mathematics to the real world | 1413 | 02:04 | |

| 10. Designing aeroplanes | 1238 | 02:39 |

Between the moment when you start designing an aeroplane and the moment when it starts firing, you know, bom-bom-bom in the air, is going to be three years or so; so towards the end of the war we were actually designing civil aeroplanes. It was quite clear that nothing we started designing then was going to be flying in time to be any use in the war. So, in fact, I spent three or four years designing civil stuff at the end, which was rather frustrating actually, but there it is.

[Q] And you were using your mathematical skills then?

Yes, I was not only using mathematical skills - I don't regret the engineering training, in a way, in fact, I don't regret it at all really. It teaches you that mathematics... how to use mathematics. I mean, how to... it first of all teaches you a great faith in mathematical models. I mean, I don't know whether you realise this but up till the 1950s, certainly all the time when I was designing aeroplanes, we designed aeroplanes very successfully, on... one of the assumptions we made was that air is incompressible. Everybody who's pumped up a bicycle tyre knows that air is compressible, but the assumption was that air was incompressible, and it's a perfectly safe assumption to make when designing an aeroplane so long as it doesn't go close to the speed of sound, which in those days, we didn't. In other words, I learnt that you make models, making assumptions that air is incompressible, that metals obey Hooke's Law, which are safe enough to trust your life to. You know, you can go in up in the aeroplanes and they don't crash. And... so I learned how to make models and to put faith in models. Which is not... I don't think I learned any new mathematical techniques as an engineer - the one thing I'll say for Eton is they taught me a lot of straight mathematics - but it did teach me how you apply mathematics to the real world, and to put faith in models of the real world.

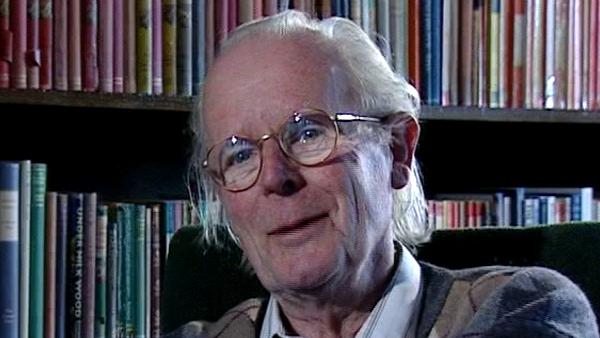

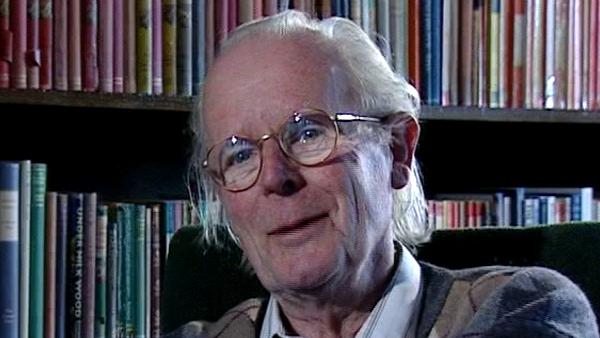

The late British biologist John Maynard Smith (1920-2004) is famous for applying game theory to the study of natural selection. At Eton College, inspired by the work of old Etonian JBS Haldane, Maynard Smith developed an interest in Darwinian evolutionary theory and mathematics. Then he entered University College London (UCL) to study fruit fly genetics under Haldane. In 1973 Maynard Smith formalised a central concept in game theory called the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS). His ideas, presented in books such as 'Evolution and the Theory of Games', were enormously influential and led to a more rigorous scientific analysis and understanding of interactions between living things.

Title: Applying mathematics to the real world

Listeners: Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins was educated at Oxford University and has taught zoology at the universities of California and Oxford. He is a fellow of New College, Oxford and the Charles Simonyi Professor of the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University. Dawkins is one of the leading thinkers in modern evolutionary biology. He is also one of the best read and most popular writers on the subject: his books about evolution and science include "The Selfish Gene", "The Extended Phenotype", "The Blind Watchmaker", "River Out of Eden", "Climbing Mount Improbable", and most recently, "Unweaving the Rainbow".

Tags: Eton College

Duration: 2 minutes, 5 seconds

Date story recorded: April 1997

Date story went live: 24 January 2008