NEXT STORY

Researching disease susceptibility

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Researching disease susceptibility

RELATED STORIES

I had a call from a young woman in... from, well, she was in Boston then, and she was a graduate student doing her degree in economics and her name was Emily Oster. And she said that she'd read about the stuff, about the gender ratio and she'd gotten very interested in… in that and she had spent the next year or more collecting data to test in effect the predictions that you'd make from that model. Well, one of the predictions were if you looked just at broad population data, you'd expect there'd be a direct correlation between gender ratio, that is, males and females and the prevalence of hepatitis B. You know, the higher... if you have high prevalence, you have high gender ratios. If you have low prevalence of hepatitis B, you have low gender ratios. Well, she collected all that data from the medical literature and from demographic data from WHO and so forth and sure enough, there's a very high correlation, including China, you know, where they have one of the highest prevalences of HBV and one of the highest gender ratios, male to female. Okay, so that was pretty convincing. Then she went on to do some other things. She's very mathematically-oriented and she made some really fascinating mathematical models for all this.

So then the next thing was there'd been a nearly universal vaccination program in Alaska because Inuits, Eskimos, have a very high prevalence of hepatitis B, strangely. Other Native Americans, Indians, don't and… and Europeans of… and… and Alaskans of European origin don't have particularly high frequency, but the vaccination program was in place for about 15 years. It had been highly effective. Among the Native Americans back before vaccinations, they had 200–300 cases of hepatitis a year, after 10 years, zero. It was acute hepatitis and the prevalence went down. So she looked at the vaccination data. So the model is, okay, you would expect that you would get a decrease in gender ratio in the Inuits and the Eskimos because they were under… they were influenced by the hepatitis infection but not the Indians or in people of European origin. That's exactly what she found and she did a similar but rather more sophisticated study in Taiwan and the results were complex but generally speaking...Okay so that, first of all that… that was a direct test of the model, right? And now that meant it's ideologic and it causes the germ because if you remove it, the gender ratio changes... That's not a disease, you know. Having a boy or a girl isn't a disease. That… effect, a profound effect on human populations. Now it's hard to tell what, you know, there're a lot of things that determine gender ratio. At an individual level, it might be hard for anybody to know, but at a demographic level, at a population level, in a place like China which is moving towards a universal vaccination and where they have one child, there's a one child rule, which is pretty strictly adhered to, except, with some exceptions by the way, foreign families, minorities, you know, can have more than one child. Now, there may be some effect, you know, may not influence single childs [sic] as much as it does whole communities. We never actually did a study in China but nevertheless this raises that… this raises that question about the demographic effect. Now as far as I know, nobody's ever looked in humans anyhow on viral effects on gender ratios. There… there are studies in other… in other species and I… and there… I'm sure there are other… there other factors that have maintained this in the population.

[Q] That's fascinating. And no idea what the mechanism is?

Well, we have a bunch of ideas but we haven't… we haven't tested, you know, I'm not… I don't have a lab any more and… but I think particularly since… since Emily's research, I think there'll be more… be more work on it and I continue to speak on it and people… but you see it's… it's not the sort of thing you would do, you know, if you’re trying to, you know, if they tell you, in your department… well, listen we got to develop drugs. Are you going to work on gender ratio? Well, the answer is yes, you should because among other things, if you can figure out what that... that is, you're not going to, I mean I hope it's never used for determining, you know, for influencing gender outcome in humans, but think of what it would do in cattle raising. You know, you… you have a herd where you… you want… you have really great cows and… and you… you want to increase them or you want to raise steers, you know, your beef production, you know, your... you know, dairy production and you want… you want to be able to affect, you know, gender ratio.

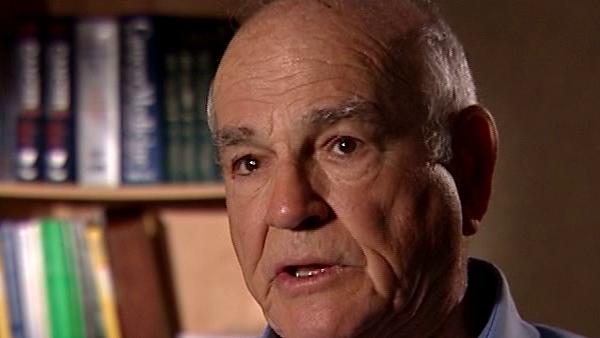

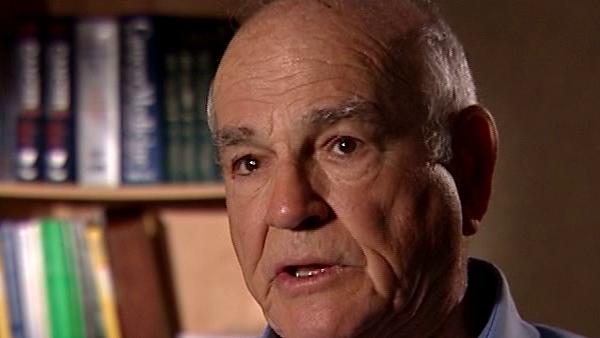

American research physician Baruch Blumberg (1925-2011) was co-recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1976 along with D Carleton Gajdusek for their work on the origins and spread of infectious viral diseases that led to the discovery of the hepatitis B virus. Blumberg’s work covered many areas including clinical research, epidemiology, virology, genetics and anthropology.

Title: Emily Oster's work on gender ratio and hepatitis B infection

Listeners: Rebecca Blanchard

Dr Rebecca Blanchard is Director of Clinical Pharmacology at Merck & Co., Inc. in Upper Gwynedd, Pennsylvania. Her education includes a BSc in Pharmacy from Albany College of Pharmacy and a PhD in Pharmaceutical Chemistry from the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. While at Utah, she studied in the laboratories of Dr Raymond Galinsky and Dr Michael Franklin with an emphasis on drug metabolism pathways. After receiving her PhD, Dr Blanchard completed postdoctoral studies with Dr Richard Weinshilboum at the Mayo Clinic with a focus on human pharmacogenetics. While at Mayo, she cloned the human sulfotransferase gene SULT1A1 and identified and functionally characterized common genetic polymorphisms in the SULT1A1 gene. From 1998 to 2004 Dr Blanchard was an Assistant Professor at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia. In 2005 she joined the Clinical Pharmacology Department at Merck & Co., Inc. where her work today continues in the early and late development of several novel drugs. At Merck, she has contributed as Clinical Pharmacology Representative on CGRP, Renin, Losartan, Lurasidone and TRPV1 programs and serves as chair of the TRPV1 development team. Dr Blanchard is also Co-chair of the Neurology Pharmacogenomics Working Group at Merck. Nationally, she has served the American Society of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics on the Strategic Task Force and the Board of Directors. Dr Blanchard has also served on NIH study sections, and several Foundation Scientific Advisory Boards.

Tags: Native American, China, Emily Oster

Duration: 5 minutes, 21 seconds

Date story recorded: September 2007

Date story went live: 28 September 2009