NEXT STORY

Should Rosalind Franklin have shared the Nobel Prize?

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Should Rosalind Franklin have shared the Nobel Prize?

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 81. How being a scientist affects the way one sees the world | 1 | 648 | 01:34 |

| 82. The complexity of a single cell | 568 | 01:50 | |

| 83. The length of a strand of DNA | 556 | 01:21 | |

| 84. George Gamow and the RNA Tie Club | 1 | 1022 | 03:05 |

| 85. How we came to write the genetic code | 597 | 01:48 | |

| 86. If not Crick and Watson then who? | 2 | 838 | 02:11 |

| 87. Should Rosalind Franklin have shared the Nobel Prize? | 2173 | 00:36 | |

| 88. Which field of science is the right one for you? | 1 | 686 | 02:05 |

| 89. Getting the balance right between work and relaxation | 767 | 01:31 | |

| 90. What is at the bottom of consciousness? | 1 | 1100 | 02:33 |

It isn’t quite clear who would’ve done it, because if we hadn’t done it, we would’ve thought that Linus Pauling would have had another go, but... it wasn’t clear that he wasn’t rather enamoured of his original structure. But after he’d seen Rosalind Franklin’s data I don’t see how he could’ve stuck to his original structure. I think he would’ve… bound to have a second attempt. The person who should’ve gone on to do it was Rosalind Franklin, but she moved from the lab because she didn’t get on with Maurice Wilkins, she moved to Birkbeck, under [John Desmond] Bernal, and the condition was made, I think improperly, that she shouldn’t go on working on DNA, so she didn’t do further work on it. But even so, Maurice Wilkins would’ve gone on and done the work, and encouraged by us to build models and a little prodding and so on, and I think he would’ve probably got there, he… either he or Pauling would’ve got there within two or perhaps three years or something of that sort. And I don’t… can’t help feeling that in both cases they would’ve seen the implications of the structure. Although they… they… I don’t... they necessarily have seen it quite as quickly because, of course, we saw it immediately because our minds were prepared for the implications, but it… they would’ve been seen… if they hadn’t seen it we would’ve certainly seen it. So… so, it did accelerate… it did accelerate the thing. It… probably the useful thing as far as I was concerned is it gave me a certain entrée to people because they were interested in it, and they wanted me to exert some influence in the way the experimental work went by going around giving a lectures and trying to get people to think about the problem. Because, you realise, people didn’t think about these problems before. They were totally new way of looking at things, or they thought they were problems for the future. I mean, that’s… that’s a common… a common thing when you have situations of this type that people think yes, that is a problem, but it’s premature to attack it now. That’s what a number of neuroscientists feels about trying to attack consciousness, they say, well yes, in the long-run, of course we’ve got to solve that problem but, you know, we’re busy now doing useful things and it’s premature to go on and do it. So… and maybe… sometimes it is premature. You don't know until you've tried.

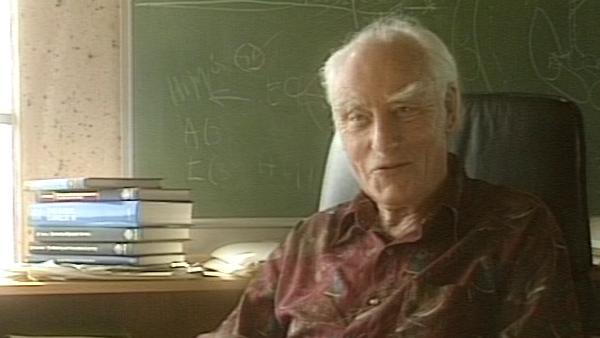

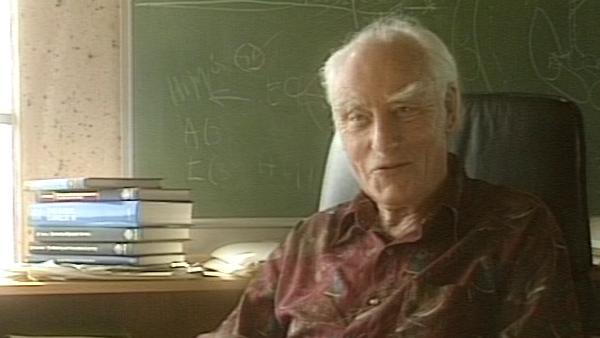

The late Francis Crick, one of Britain's most famous scientists, won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. He is best known for his discovery, jointly with James Watson and Maurice Wilkins, of the double helix structure of DNA, though he also made important contributions in understanding the genetic code and was exploring the basis of consciousness in the years leading up to his death in 2004.

Title: If not Crick and Watson then who?

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: Birkbeck College, Linus Pauling, Rosalind Franklin, Maurice Wilkins, John Desmond Bernal

Duration: 2 minutes, 11 seconds

Date story recorded: 1993

Date story went live: 08 January 2010