NEXT STORY

Science and the soul

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Science and the soul

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 51. The complexities of working on the brain | 624 | 01:09 | |

| 52. How does the brain control memory and consciousness? | 639 | 01:50 | |

| 53. The question of qualia | 922 | 01:55 | |

| 54. Science and the soul | 656 | 01:09 | |

| 55. How do we see? | 670 | 04:03 | |

| 56. An argument in favour of animal experimentation | 1 | 473 | 02:08 |

| 57. Is the knowledge we have the knowledge we need? | 439 | 01:01 | |

| 58. What's happening in molecular biology now? | 461 | 01:30 | |

| 59. Visual illusions | 1 | 430 | 01:40 |

| 60. The importance of the discovery of DNA | 876 | 02:44 |

The key question is what philosophers would call ‘qualia’: the redness of red. What explains the redness of red? Or, in other words, what explains the fact that you are aware of things? It’s not easy to define these terms; in fact it’s better not to. But you all know… everybody knows roughly what they mean to be conscious because they know where they’re in a dream… in a deep, dreamless sleep, they’re not conscious or when they’re under an anaesthetic, they’re not conscious. They… they actually know that there are these… they can be in such states where they’re not conscious, and the real question is what’s the difference in the brain when you’re under an anaesthetic, a deep anaesthetic for example, on the one hand, and when you’re awake? Because it isn’t true the brain just packs up. All sorts of things go on and if you had your eyes taped open and… and signals…sent into your eyes, then part of your brain would react just as it would if you were awake. But there must be differences and we don’t know what those differences are. And it turns out, not many people in the past have been very interested in finding out because they found so… so many interesting things working on anaesthetised animals that for a long time they didn’t even work on alert animals. Now they work on alert animals, but they’re not necessarily trying to find the difference between the anaesthetised ones and the alert ones. And that’s one of the problems which certain people say will never be explained by science… explained… it's something outside science is required to explain that. The only way we could refute that would be to explain it by science and produce such a… a convincing explanation backed up by so much experimental data that we could say the other hypothesis, that there has to be something extra, is not needed. That’s, of course, the furthest we could go. We’re a long way off that yet. How long, I wouldn’t like to say.

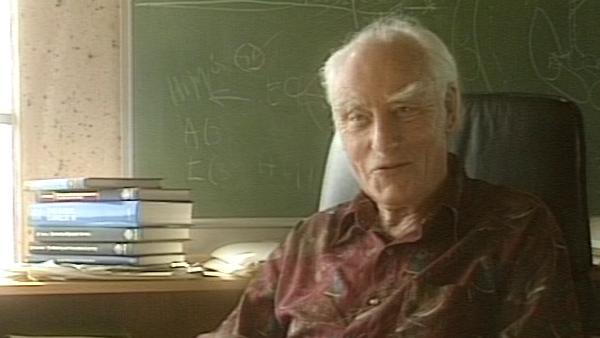

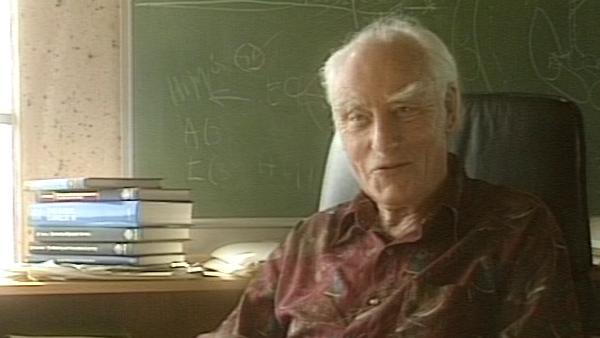

The late Francis Crick, one of Britain's most famous scientists, won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. He is best known for his discovery, jointly with James Watson and Maurice Wilkins, of the double helix structure of DNA, though he also made important contributions in understanding the genetic code and was exploring the basis of consciousness in the years leading up to his death in 2004.

Title: The question of qualia

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: qualia, consciousness, brain, anaesthetic, science

Duration: 1 minute, 55 seconds

Date story recorded: 1993

Date story went live: 08 January 2010