NEXT STORY

Becoming a soil mechanic

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Becoming a soil mechanic

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Playing with aeroplanes | 2 | 809 | 01:56 |

| 2. Humiliation at school | 644 | 03:26 | |

| 3. Beautiful bridges inspired my study in civil engineering | 285 | 02:19 | |

| 4. Becoming a soil mechanic | 364 | 01:30 | |

| 5. Hitch-hiking up Africa | 326 | 02:39 | |

| 6. Wild times in Soho | 340 | 00:45 | |

| 7. A tale of two cities | 430 | 01:13 | |

| 8. Switching to cell biology | 372 | 05:55 | |

| 9. Early work in cell biology: The Fluid Membrane model | 260 | 02:49 | |

| 10. 'You chop off its head it regenerates it' | 334 | 04:53 |

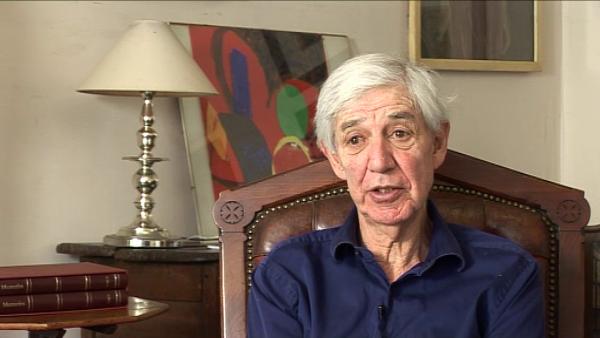

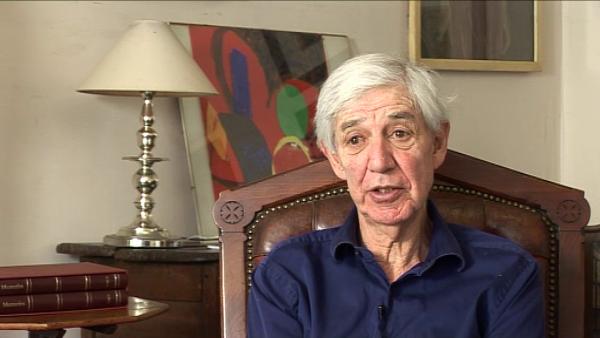

My mother really wanted me to be a plumber and that wasn’t quite what I had in mind for myself. And... I then decided I wanted to be... do engineering and I chose civil engineering; it seemed less greasy than mechanical engineering, and electrical engineering I wasn’t that keen on, nor was I that keen on chemical engineering. And I thought the beautiful bridges that I saw, which... I... which I’d seen illustrated, encouraged me to do civil engineering. So I went to the local university and did civil engineering. It was okay, I enjoyed the maths most, and in fact, in doing civil engineering, I really wanted to be a mathematician because it was the maths I liked most, but I really wasn’t good enough. And I... funnily enough, I... it... it was quite amusing how I finally got through my civil engineering because, first of all, I was quite good at spotting questions and in our fourth year at university — for the final exams — we had to design a water tower and a bridge and the external examiners — we took about six months designing these — and the external examiner came and examined me, and he showed that my water tower would leak and my bridge would fall down, but he put his arm around me and said, 'But I think you’ve got the right idea, young man', and passed me on that basis. I’d made a couple... couple of arithmetical errors. And then for the final exam, we... I did the spotting for a friend and myself, but I spotted badly and I thought we’d failed, ‘cause I hadn’t done well in the exam, but…What’s spotting? Well in other words, predicting what questions would actually come up in the exam. I... I used to be quite good at it, but I did it badly for the final exam. However, I did notice they’d made two mistakes in the exam papers, they’d put a three where there should be a two and, you know, for a particular proof of something or another, and I went to the examiner and said: ‘You cannot fail us, you’ve made two mistakes’. And they passed us.

Lewis Wolpert (1929-2021) CBE FRS FRSL was a developmental biologist, author, and broadcaster. He was educated at the University of Witwatersrand (BSc), Imperial College London, and at King's College London (PhD). He was Emeritus Professor of Biology as applied to medicine in the Department of Anatomy and Developmental Biology at University College London. In addition to his scientific and research publications, he wrote about his own experience of clinical depression in Malignant Sadness: The Anatomy of Depression (1999).

Title: Beautiful bridges inspired my study in civil engineering

Listeners: Eleanor Lawrence

Eleanor Lawrence is a freelance science writer and editor, and co-author of Longman Dictionary of Environmental Science.

Tags: civil engineering, maths, bridges, spotting

Duration: 2 minutes, 19 seconds

Date story recorded: April 2010

Date story went live: 14 June 2010