NEXT STORY

On being a human guinea pig

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

On being a human guinea pig

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The box that attracted me to science | 1 | 1012 | 01:37 |

| 2. My scientific education | 2 | 403 | 03:59 |

| 3. The difference between precision and accuracy | 468 | 04:26 | |

| 4. On being a human guinea pig | 1 | 274 | 03:10 |

| 5. How JBS Haldane made his liver fizz | 2 | 644 | 00:42 |

| 6. Health and safety hampers science today | 306 | 01:06 | |

| 7. How I invented the electron capture detector | 428 | 06:10 | |

| 8. What is the meaning of life? | 2 | 526 | 04:12 |

| 9. An invitation from NASA | 3 | 296 | 02:51 |

| 10. Detecting life on Mars | 1 | 344 | 04:20 |

An interesting thing happened when I got to Manchester that revealed the importance of the training I got as a technician. I'd only been about a month in the department there and the professor who was Alexander Todd, a very famous chemist who became a Nobel Prize winner later and after that became Lord Todd, President of the Royal Society is one of our most distinguished scientists. Anyway, I was lucky to have him as a young professor. After I had been there a month he suddenly called me into his office and said, 'Lovelock, you've cheated. I'm angry we've let you in on your second year with special consideration and you've let me down'. And I thought, what on Earth is he on about? And he went ranting on and he said, 'You're very stupid'. He said, 'You turned in the results of a student exercise that were exactly right. You should have known that students never get the right answer. And you're stupid because most students who do this kind of thing copy the correct result from the invigilator's book down and pretend they've done the experiment, move it a little way from the right answer just so we don't realise what they've done.' And it took me nearly 20 minutes to explain to him that I was a pro at that particular analysis which was the amount of bromide ion in a solution in water - just the kind of thing that was done for photographic chemistry - and I could get the right answer every time. He just still didn't believe me and it wasn't until two weeks later he came to see me do a gravimetric analysis of the sulphate ion, which is much more difficult that he realised there was a difference between somebody who had been taught to do science professionally and the average student. And I think we both wondered then what the university training was all about. Was it producing scientists or was it producing people who could pass examinations in science, which is a very different thing. And that particular little episode came back to haunt me very many years later. I was involved with the discovery of the chlorofluorocarbons in the air which led to, of course, all the concern about the depletion of the ozone layer and so on. Now, I'd made my measurements as accurately as I could, I was the first person to measure them, but I didn't think they were all that accurate, I thought they were about 20% because measuring things at the part per trillion level is very, very difficult. But, American scientists all claimed that they could measure these things down to 1% accuracy. I was very impressed, I knew they probably got very high-tech apparatus compared with my home-made equipment and they must be very good. And it went on for a while until the National Bureau of Standards in America grew rather suspicious of what was going on. And did a survey of all the labs that were claiming to measure chlorofluorocarbons in the atmosphere and they found that far from being 1% accurate their results scattered over 400%. It was a result mostly of, not always, but in some bad cases of scientists confusing precision with accuracy. Many people do. You know, for example, I can say that your weight is precisely 91 pounds on my weighing machine. It obviously isn't, but the weighing machine will show it precisely as that every time you stand on it. That's precision and inaccuracy. On the other hand, I could have a variable weighing machine that gave you a weight of anything between 91 and 250 pounds, but somewhere in the middle, if you took enough readings, it was accurate and it's important to recognise this difference and I'm afraid a lot of scientists don't, probably because of the nature of university teaching. It's not important to them to know it. Anyway, it all took me back to my experience with Professor Todd and the teaching in universities, and I think this is a problem in science generally.

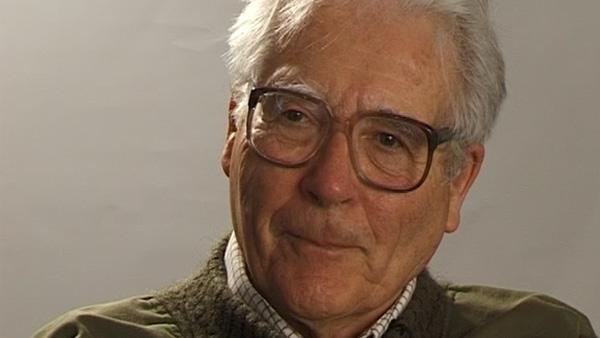

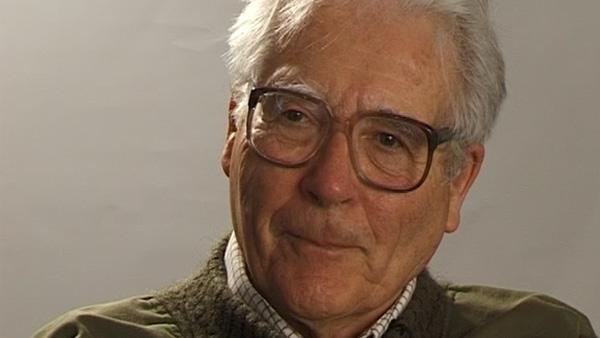

Born in Britain in 1919, independent scientist and environmentalist James Lovelock has worked for NASA and MI5. Before taking up a Medical Research Council post at the Institute for Medical Research in London, Lovelock studied chemistry at the University of Manchester. In 1948, he obtained a PhD in medicine at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and also conducted research at Yale and Harvard University in the USA. Lovelock invented the electron capture detector, but is perhaps most widely known for proposing the Gaia hypothesis. This ecological theory postulates that the biosphere and the physical components of the Earth form a complex, self-regulating entity that maintains the climatic and biogeochemical conditions on Earth and keep it healthy.

Title: The difference between precision and accuracy

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: Manchester University, National Bureau of Standards, USA, Alexander R Todd

Duration: 4 minutes, 27 seconds

Date story recorded: 2001

Date story went live: 21 July 2010