NEXT STORY

How JBS Haldane made his liver fizz

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

How JBS Haldane made his liver fizz

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The box that attracted me to science | 1 | 1012 | 01:37 |

| 2. My scientific education | 2 | 403 | 03:59 |

| 3. The difference between precision and accuracy | 468 | 04:26 | |

| 4. On being a human guinea pig | 1 | 274 | 03:10 |

| 5. How JBS Haldane made his liver fizz | 2 | 644 | 00:42 |

| 6. Health and safety hampers science today | 306 | 01:06 | |

| 7. How I invented the electron capture detector | 428 | 06:10 | |

| 8. What is the meaning of life? | 2 | 526 | 04:12 |

| 9. An invitation from NASA | 3 | 296 | 02:51 |

| 10. Detecting life on Mars | 1 | 344 | 04:20 |

I left university at about the age of 21 and was exceedingly lucky to get a job at the National Institute for Medical Research in London which in those days was at Hampstead in an old disused hospital. Now, the reason I was lucky was that my professor, who I've already mentioned, Todd, at Manchester, happened to have as his father-in-law Sir Henry Dale who was director of that institute and apparently Sir Henry Dale had asked him 'Do you have a young scientist who could take, available for a job that we have here'? And for some reason Todd recommended me. I don't know whether it was the cheating episode that made him, because a got a very poor degree only, a bottom second from Manchester and they normally only employed Oxbridge people there.

Anyway, I got this job and it was wartime then of course in 1941, and academic science had gone to the winds. It was all ad hoc problems to deal with the war. Problems that had to be solved yesterday if possible. And one of these problems that landed in our court was how, methods of preventing burns to service personnel under battle or naval condition, naval battle conditions. Because burns are very disabling injuries, but they're very frequent during warfare. And one of the first things we needed to know was what's the heat radiation flux that causes first, second or third-degree burns. First, second and third-degree, of course, are intensities of burning. A first-degree burn is not much more than a reddening of the skin which will heal spontaneously. Second-degree produces blisters and third-degree destroys the top surface of the skin completely.

Anyway, we wanted to know the radiation flux and they told us to find it out by exposing the skin of shaved rabbits to radiant heat at different magnitudes to produce this effect. My colleague, a chap called Owen Lidwell, I looked at one another and thought, oh we can't do that, it's… It might be alright for biologists, but it's much too cruel a thing to do. Even though the animals were anesthetised, they'd have a lot of pain when they came to. And so we thought, well we can't let anyone else do it, we have to do it on ourselves. And we did and it was exquisitely painful at first, as you can imagine, but a very peculiar thing happened. I don't know whether it was the fascination with the results we were getting or whether there was more to it, but we both found that the pain of burning gradually diminished as we went on doing and towards the end it was not more than the pressure. And to this day I can hold a red-hot object against my skin and not feel any sense of pain. It could burn of course, I don't like doing it, but it'll… it's not a painful experience. It doesn't work with toothache.

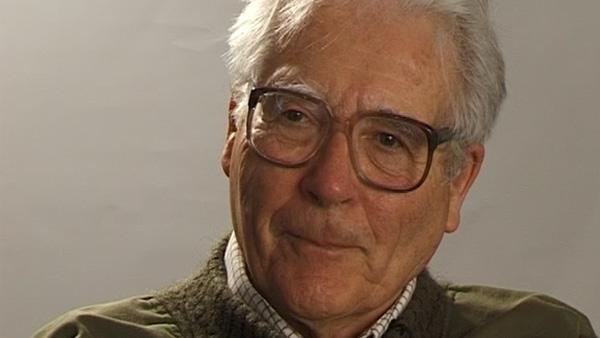

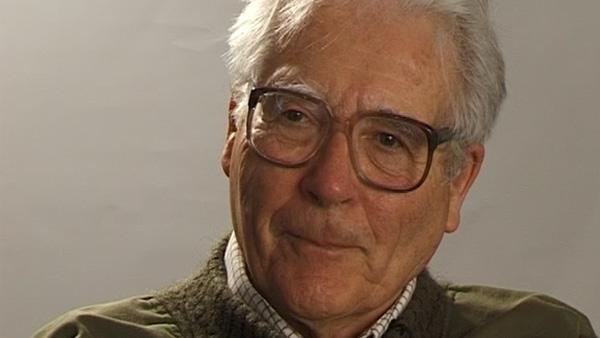

Born in Britain in 1919, independent scientist and environmentalist James Lovelock has worked for NASA and MI5. Before taking up a Medical Research Council post at the Institute for Medical Research in London, Lovelock studied chemistry at the University of Manchester. In 1948, he obtained a PhD in medicine at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and also conducted research at Yale and Harvard University in the USA. Lovelock invented the electron capture detector, but is perhaps most widely known for proposing the Gaia hypothesis. This ecological theory postulates that the biosphere and the physical components of the Earth form a complex, self-regulating entity that maintains the climatic and biogeochemical conditions on Earth and keep it healthy.

Title: On being a human guinea pig

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: National Institute for Medical Research, Hampstead, Alexander R Todd, Henry Dale, OM Lidwell

Duration: 3 minutes, 11 seconds

Date story recorded: 2001

Date story went live: 21 July 2010