NEXT STORY

An invitation from NASA

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

An invitation from NASA

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The box that attracted me to science | 1 | 1012 | 01:37 |

| 2. My scientific education | 2 | 403 | 03:59 |

| 3. The difference between precision and accuracy | 468 | 04:26 | |

| 4. On being a human guinea pig | 1 | 274 | 03:10 |

| 5. How JBS Haldane made his liver fizz | 2 | 644 | 00:42 |

| 6. Health and safety hampers science today | 306 | 01:06 | |

| 7. How I invented the electron capture detector | 428 | 06:10 | |

| 8. What is the meaning of life? | 2 | 526 | 04:12 |

| 9. An invitation from NASA | 3 | 296 | 02:51 |

| 10. Detecting life on Mars | 1 | 344 | 04:20 |

What is the meaning of life? Well, this is a question that has haunted me throughout the whole of my scientific career. It started when I was working at the National Institute for Medical Research at Mill Hill in the 1950s. And I was working in, at that time, in the Division of Experimental Biology and the task that I had been set was to find out what was the nature of the damage suffered by living cells when they are frozen and thawed, and how do you prevent it. Now, my biologist friends were working with all sorts of living cells and even whole animals a little bit later. I decided that the best model cell to use, to find out the nature of freezing damage, was the red blood cell. You know, the little red thing that swims around in your blood and carries oxygen. I chose it because very conveniently if a red blood cell gets damaged or bust, it lets out its red pigment and you can easily measure this quantitatively, and you get accurate results for your experiments. And I happily went on and produced a couple of papers on this, which seemed to answer the whole question of the nature of the damage caused by freezing and thawing. Indeed, the second paper in that series became a citation classic, the most cited paper in biology. But my biologist friends and people around immediately said, 'But you've wasted your time, and you wasted our time. You should never have chosen red blood cells, they're not alive! They can't reproduce, so they're not alive. You should have chosen a living cell to do your work with. You'll have to do it all over again'. So, I moved on to work with – being a fairly compliant sort of character – to work with spermatozoa. I said, 'Are these alive'? And they said, 'Oh yes of course they are the units of reproduction'. Of course, I think they're crazy because spermatozoa don't divide or split. They're only part of a process. But nevertheless, they were quite happy with that and you could see them swimming. I thought that the biologists were being a little bit dogmatic about their definition of life being solely determined by reproduction. I thought that metabolism and the ability to self-regulate to keep itself in a constant state in the face of attrition were also attributes of life just as important. And it so happens that red cells do have enzymes, they do have systems, they keep their internal contents exactly constant, they self-regulate. In other words, they behave just like a living organism. That they can't reproduce to me seemed to be a lesser matter.

Well, this business was to come back to haunt me again many years later when I introduced the concept that the Earth is a self-regulating system, just like one of these red blood cells. It can regulate its climate and its chemical composition and biologists, notably Richard Dawkins, who writes wonderfully well, jumped on this instantly. 'But this man is saying the Earth is alive, this is ridiculous! It cannot reproduce, it cannot compete with other planets and so become selected as the best planet', and so on. And, I'm afraid this has haunted me for a long time because I think he's still saying this, although his biologist colleagues, particularly his mentor William Hamilton, who is now sadly dead, had begun to see that indeed the Earth does self-regulate and the only quarrel now is on the meaning of life. Is it alive or is it not alive? I'm inclined to think that it is alive in certain ways. They won't have it because it doesn't reproduce. That's a small matter. The important thing about the self-regulating Earth, and that now that most scientists agree about it, is that we have to understand that the Earth is a system that includes the life on it just as much as it includes the geology and geophysics and all the rest of it. If we are to live through this century and not perturb it too far so that conditions change and become uncomfortable for our civilisation.

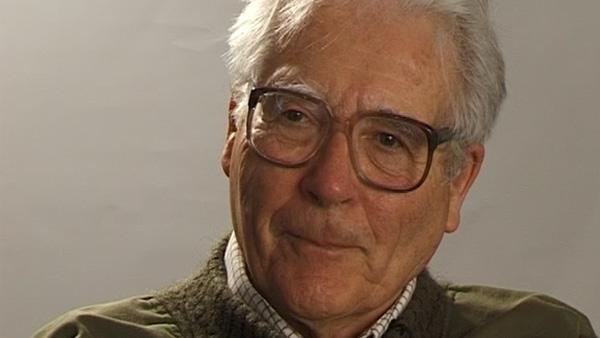

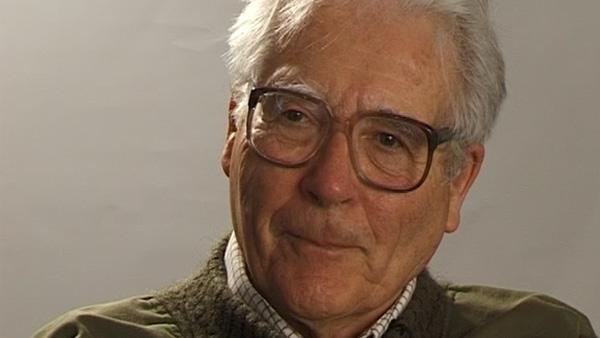

Born in Britain in 1919, independent scientist and environmentalist James Lovelock has worked for NASA and MI5. Before taking up a Medical Research Council post at the Institute for Medical Research in London, Lovelock studied chemistry at the University of Manchester. In 1948, he obtained a PhD in medicine at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and also conducted research at Yale and Harvard University in the USA. Lovelock invented the electron capture detector, but is perhaps most widely known for proposing the Gaia hypothesis. This ecological theory postulates that the biosphere and the physical components of the Earth form a complex, self-regulating entity that maintains the climatic and biogeochemical conditions on Earth and keep it healthy.

Title: What is the meaning of life?

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: National Institute for Medical Research, London, Richard Dawkins, WD Hamilton

Duration: 4 minutes, 13 seconds

Date story recorded: 2001

Date story went live: 21 July 2010