NEXT STORY

How the vernacular language of traditional art influenced my work

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

How the vernacular language of traditional art influenced my work

RELATED STORIES

When did you meet Pupal Jayakar?

Pupal Jayakar was the person who sort of invited me to join, and Pupal Jayakar didn’t know me before. But I had a friend in Riten Majumdar who was Sucheta Kriplani’s brother who studied in Santiniketan and was very close to Benode Bihari, and he ended up as a designer. So Pupal knew him. So, Riten Majumdar at that time had an offer to go to Yugoslavia on a scholarship. So she probably talked to him saying that we have a design centre here, so could you suggest anybody’s name there. Then he knew, Riten knew that I had some interest in getting into the industry. That’s how I came to know him. After that we have been sort of reasonably friendly and she was in a way a dynamic woman, and she had a kind of a fairly comprehensive idea of what the craft scene should get at that time. She worked at a certain level in the government that she could get things done. So it was a good association and she was quite supportive. So when I was leaving she was very unhappy, Senzatigar [?], but I said at least you can arrange for my showing what I did in the 2 years in two exhibitions so that people can know, and also know why a government organisation is not able to deliver the goods. So we had an exhibition at the Jehangir Art Gallery, a big one, and later in Delhi in the All India Fine Arts and Crafts Society with samples of the various works we had done for the craft scene, starting with the lowest price to the highest price. All these things were not utilised by the Board to sort of get into the market, so we said that this is because that they do not want their traditional contracts to be broken. So I said we will book all this year on this, it’s not because the market is insensitive but the government is insensitive, and then we could prove it to them. Within 1 week that we had booked, the orders were on a lakh of rupees and then even giving them the whole way of getting them executed. But later I came to know that nothing was executed. They didn’t go at all. Anyway, I was happy to have had that experience at that time.

But you don’t feel you really changed anything?

Huh?

Do you feel you did change something?

Well, to a certain extent perhaps by the kind of samples we produced probably found it filtered into the market a certain kind of visual access. But then these changes are very sort of temporary, I mean transitory. I did, while doing this, various kinds of tapestries with the sort of bits of yarn we had thrown away, and one or two of these tapestries got shown outside and went into the New York Trade Fair, and there was a turnabout and probably publicised. Then what happened? Well, here everyone started taking small tapestries to put on the wall and they were very intelligent, to say the least. It became a kind of a, sort of a sales commodity, you know, this kind of a thing. So, how you affect the market is a very difficult thing, unless sort of you are constantly pummelling public taste with high quality goods or highly designed. Well, the trade pulls, they pulled it down, they vulgarised it very soon. This happens. Anyway, that experience has been very good for me, and I also came to know why, how our whole, what you call, the functional art scene is suffering just because the government doesn’t have the right kind of attitude towards functional art, and how their kind of development, philosophy of development doesn’t also think in terms of it. I was a member - I was a member of the Handicrafts Board for many days. I put it down in writing; I talked to them and all. That hasn’t changed. That hasn’t changed. In fact, Pupal Jayakar when she turned 70, they published a volume to felicitate her. I have written a sort of long article there called Do Hands Have a Chance? kind of a thing. Now, to pinpoint how the government’s attitude has been sort of changing in a sort of a ridiculous way, how in what is called globalising society we are sort of losing sight of the essentials and sort of taking greater notice of the non-essentials, this kind of thing.

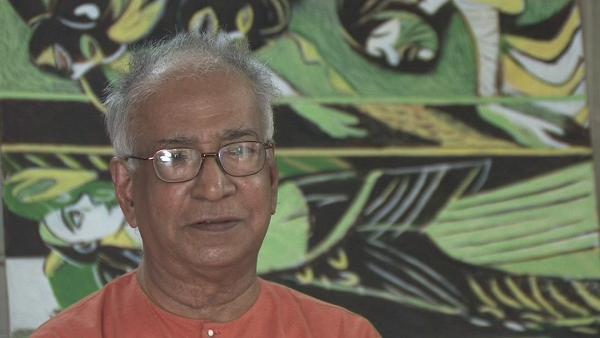

KG Subramanyan (1924-2016) was an Indian artist. A graduate of the renowned art college of Kala Bhavana in Santiniketan, Subramanyan was both a theoretician and an art historian whose writings formed the basis for the study of contemporary Indian art. His own work, which broke down the barrier between artist and artisan, was executed in a wide range of media and drew upon myth and tradition for its inspiration.

Title: The government's attitude towards India's art

Listeners: Timothy Hyman

Timothy Hyman is a graduate of Slade School of Fine Art, London, in which he has also taught. In 1980 and 1982, he was Visiting Professor in Baroda, India. Timothy Hyman has curated many significant art exhibitions and has published articles and monographs on both European and Indian artists.

Duration: 6 minutes, 3 seconds

Date story recorded: 2008

Date story went live: 10 September 2010