NEXT STORY

Realising the importance of the Hamzanama

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Realising the importance of the Hamzanama

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21. Going to study at the Royal College of Art in London | 85 | 05:39 | |

| 22. Visiting museums and travelling in Europe | 41 | 06:40 | |

| 23. Developing my work, David Hockney and RB Kitaj | 100 | 03:02 | |

| 24. Social life in London | 54 | 04:02 | |

| 25. Moving back to India and my love of travelling | 42 | 03:59 | |

| 26. Meeting my wife, Nilima, and company painting | 90 | 05:18 | |

| 27. Realism and the Ajanta Cave paintings | 61 | 05:50 | |

| 28. Emperor Akbar and the Hamzanama | 80 | 08:20 | |

| 29. Realising the importance of the Hamzanama | 58 | 01:03 | |

| 30. More on company painting | 45 | 03:22 |

Do you think it could be argued that, however, that in company painting, and even in fact in Bhupen Khakhar the hybridity is there, the match is a little less, a little less homogenous?

Quite true.

And then something is altered?

Well, that kind of hybridity is what interests me, and I think in a way it also interested Bhupen very much, and this is something which I still argue about. You see, you don’t have to merge everything to make it into a homogenous entity. I think that kind of homogenous entity, in the end it is the death. What is, what is the dynamism of these living elements in interaction with each other, even conflicting, is something which is, I think, close to life in some ways. And I think that is what I like to keep alive, you know, that, and I saw that Hamzanama was an actual specimen of that, which was painting at the Court of Akbar. It is the story which is often considered to be the story of, I mean its name is associated with the Prophet’s uncle, but it was also a rebel in the time of Harun al-Rashid. But it’s a fictional story, a fictional tale. I think there are hundreds of stories, and they were all tales. And these were narrated to Akbar, Emperor Akbar, the Mughal emperor, and so he, it looks like he made his artists to paint it, and this was painted for 15 years in which Indian, Persian and... Indian and Persian artists were involved, who also incorporated elements from European art. We call that the Court of Akbar. The Portuguese missionaries had brought plantains, polygraph bible with illustrations. I think they were etchings from Antwerp, if I am not mistaken, and these served as a basis for them to, let us say, incorporate within their kind of naturalism that they had developed. So Persian, there is a particular kind of naturalism that is in 15th, 16th Century Persian painting. Indian painting had its own way of looking at both the world and also articulating in, basically in human form, a kind of naturalism, and this was the third. And I think what came together in the form of interaction was Hamzanama. When the same idiom is applied in a more homogenous form, in the life story of Akbar you find that it had lost the spark. It had lost that kind of energy, and also the kind of dynamism which Hamzanama displays.

Can I just say, isn’t the point for you partly that the artists from the different regions, and even from totally different traditions, were working together on the same sheet?

Often, yes.

Which is astonishing.

But I would not be surprised to go back to Ajanta and say that there were multiple guilds and not one from India, and when you say guilds, you know, if they came from the South, that would be an entirely different tradition than the guild that was from the North, because the North would mean as far as let us say, you know, Kandahar, Afghanistan, because that tradition had travelled that far. What I am trying to articulate is the fact that even in the paintings like Ajanta there would be multiple hands because it’s a project which was a pet project. Such a large project, you would have to, and then they were painted at different periods. Sometimes not with great gaps between them, let’s say after 30 years another group came and painted that wall, or sometimes even finished that wall which was left unfinished by the other. But it is also quite likely that the guilds shared their craftsmen, guilds shared their artists. You know, if somebody was sick or ill and was not available, they would borrow somebody, you know, some others. Well, that is one thing, but at the Mughal court it was actually, it was an experiment. It was undertaken as a kind of a great experiment to, in one sense I think it is to define the great plurality of India. I think it was done through art. Well, Akbar as you know was interested in belief systems in the religion, so he used to collect all these representatives of different faiths. He had the Jain monks, he had the Hindu scholars, he had the Persian scholars, he also had the Portuguese missionaries, and he used to have these...

And the Jews, he had Jews.

Huh?

He even had Jews.

He even had Jews, yah, and he was interested, in fact, he even, how shall I say, composed a new religion, if I may use that word, Din-e-Ilahi, the religion of the law of God, which incorporated all these elements, and I think it is to his credit that he didn’t enforce it, and so it didn’t become a kind of a religion. But I learned that there are a few families who worked for Akbar, their successors continued to follow. I have even come to know of a family who was in Ahmedabad. Anyway, but the painting was the major experiment, and I think it was at a workshop either in Delhi or in Agra, but mostly in Delhi where these painters, the Great Masters, whom they call the Ustad, you know, who would make a drawing. There would be those who would be well versed in let us say landscape or in... or those who would be well versed in certain kind of figuration or portraiture, those who would be adept at doing certain kind of fine arts patterns or architecture, and their hands would be brought together on a single folio. Hamza was the... what shall we call it – this was the breeding ground, this is where it happened, they actually did that, and Hamza is a very different kind of experiment because it’s not small mini... miniatures, it’s not a small folio picture. It’s large, it’s on cloth, it’s painted on cloth, and there were 1,400 pictures painted. If you put them sideways, you know, it would be more than the space of a kilometre, and that was for 15 years all these people were engaged where they tried to hone their own skills into bringing alive the story of a hero who was perhaps fictional, but in a way they had in the example of the emperor a kind of a character. So they created Hamza in a way. It’s not so much the kind of a literary story as actually the story of the life of people, and what came in the process was a vast canvas of the Indian countryside, vast kind of hoard of characters, of demons. I think there were no demons of that kind painted ever. We only paint gods and goddesses, but these kinds of demons that they have painted, they are amazing, and they are all very, you know, charged figures. They are not sort of very finely finished figures, they are sort of half men at times, and I think that is where lies the great... greatness of that.

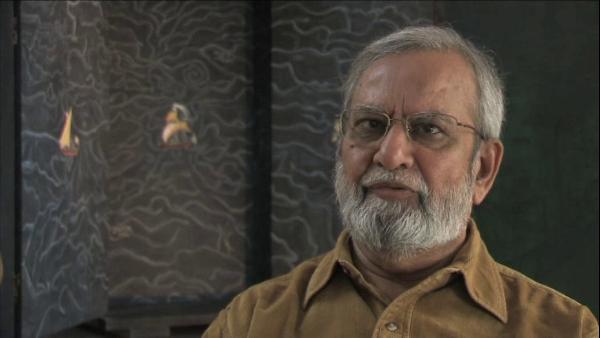

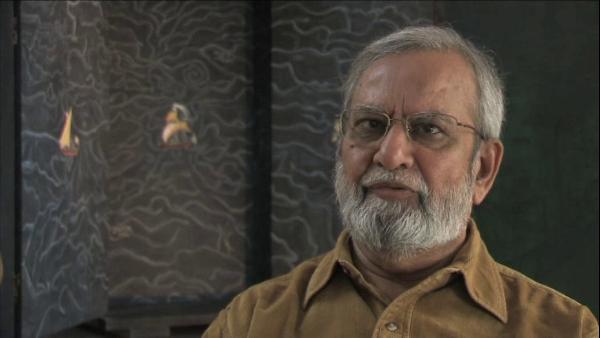

Gulammohammed Sheikh is an Indian painter, writer and art critic who has been a major figure in the Indian art world for half a century. His artistic career is closely associated with the renowned MS University of Baroda in Gujarat where after gaining his Master's degree, Sheikh went on to teach in the Faculty of Fine Arts, and where he was appointed Professor of Painting in 1982.

Title: Emperor Akbar and the Hamzanama

Listeners: Timothy Hyman

Timothy Hyman is a graduate of Slade School of Fine Art, London, in which he has also taught. In 1980 and 1982, he was Visiting Professor in Baroda, India. Timothy Hyman has curated many significant art exhibitions and has published articles and monographs on both European and Indian artists.

Duration: 8 minutes, 20 seconds

Date story recorded: December 2008

Date story went live: 18 November 2010