NEXT STORY

The effect of realism on my work and teaching

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The effect of realism on my work and teaching

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21. Going to study at the Royal College of Art in London | 85 | 05:39 | |

| 22. Visiting museums and travelling in Europe | 41 | 06:40 | |

| 23. Developing my work, David Hockney and RB Kitaj | 100 | 03:02 | |

| 24. Social life in London | 54 | 04:02 | |

| 25. Moving back to India and my love of travelling | 42 | 03:59 | |

| 26. Meeting my wife, Nilima, and company painting | 90 | 05:18 | |

| 27. Realism and the Ajanta Cave paintings | 61 | 05:50 | |

| 28. Emperor Akbar and the Hamzanama | 80 | 08:20 | |

| 29. Realising the importance of the Hamzanama | 58 | 01:03 | |

| 30. More on company painting | 45 | 03:22 |

Well, it was the East India Company that was established by the British merchant groups at one point of time which then assumed a political role and ruled over parts of India. So, there began a kind of a, what you call... a patronising painting, British patrons, and there were also those who were, let’s say, you know, anglicised Indian patrons, and Indian artists responded to this in which they began to incorporate elements of let us say quote unquote western illusionism, and new ideas. So they were not just paintings of either gods and goddesses or the epics or of the Indian stories, but life of people at one level, and these were, some of these were curious. Like I think foreigners were always interested in what the castes were in India. Among the Brahmins there are multiple castes, they are all known by the caste mark or something or with their costumes etcetera. All the communities, for instance, you know, you would have the carpenter, you will have the, you know, cloth merchant, etc. There were all types of what you call typical, stereotypical paintings made, you know, which were called Firqa. Firqa is kind of a generic term of all types of curious, you know, tradesmen paintings, you know. These were done and company paintings then branched out into doing life of people, even British for that matter, how the British lived, and the changes that it brought about in Indian life. Mostly in East India, Patna was one place which was very popular, and among other things they painted on mica. So it was a transparent, like a glass painting. Also, there were a lot of illustrations made for the British for their scientific work like ornithology or botany, and all Indian artists were employed, because that was the time when patronage to Indian miniature painting was gradually going down, and these were the new patrons for whom they painted.

But in the 1960s such paintings would be all relatively valueless, yes? I mean, they would be regarded as rather a low category of Indian art?

Yes, yes. Well, it is interesting that most art historians, who were buying art, you know, for our museums, were not buying them. Or they were at the lowest. If they bought, it would be something like a little bonus. Even they were not buying drawings let me tell you, because people were not interested in that kind of thing. You know, this is something which we got gradually interested in, but company painting was not on top.

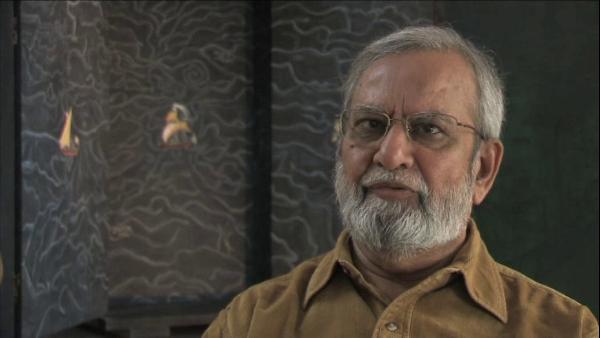

Gulammohammed Sheikh is an Indian painter, writer and art critic who has been a major figure in the Indian art world for half a century. His artistic career is closely associated with the renowned MS University of Baroda in Gujarat where after gaining his Master's degree, Sheikh went on to teach in the Faculty of Fine Arts, and where he was appointed Professor of Painting in 1982.

Title: More on company painting

Listeners: Timothy Hyman

Timothy Hyman is a graduate of Slade School of Fine Art, London, in which he has also taught. In 1980 and 1982, he was Visiting Professor in Baroda, India. Timothy Hyman has curated many significant art exhibitions and has published articles and monographs on both European and Indian artists.

Duration: 3 minutes, 22 seconds

Date story recorded: December 2008

Date story went live: 18 November 2010