NEXT STORY

Vrishchick and Lali Kala

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Vrishchick and Lali Kala

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 31. The effect of realism on my work and teaching | 63 | 01:03 | |

| 32. My wife and my children | 75 | 04:44 | |

| 33. Vrishchick and Lali Kala | 101 | 04:33 | |

| 34. Geeta Kapur and the Baroda school | 342 | 04:02 | |

| 35. The early '70s, artist’s camps and Place for People | 82 | 06:34 | |

| 36. Developing as artists and people | 58 | 04:46 | |

| 37. Pieter Bruegel and other artists | 42 | 02:50 | |

| 38. The 1975-77 state of emergency | 62 | 05:16 | |

| 39. Kabir | 43 | 06:46 | |

| 40. Benode Bihari Mukherjee and KG Subramanyan | 67 | 04:18 |

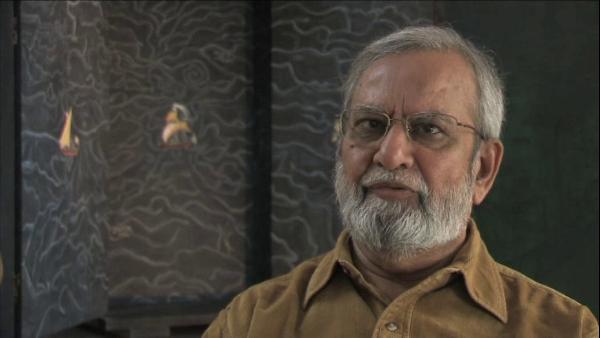

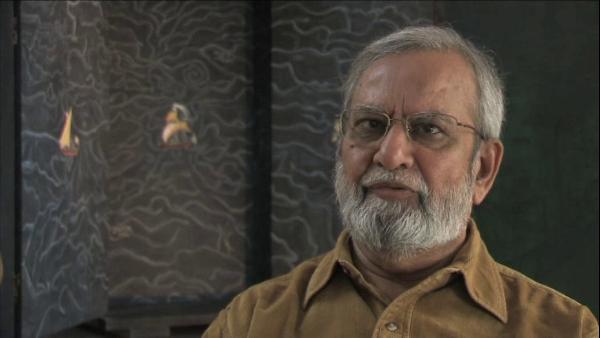

Well, I was sort of a wanderer, you know. I sort of lived a sort of a life, you know, where I could move from place to place, and even those 3 or 4 years that I was, you know, before we got married, I travelled a lot. Once or twice I did, you know, we travelled, Bhupen and Chhatpar and Nagji, I mean, but it was a kind of, I don’t know how to explain it, it’s very vague, kind of. It was a time where you were sort of floating. I think Nilima brought some kind of an anchor to that, you know, in a way made me sit down a little and made me think of my things. Also to have children was a great experience, and also I remember how she, for a period of time, even abandoned painting, her own painting to look after children, and then gradually she began to incorporate in her work images of her children and her own life, including domestic life, which not many people... actually, now if you want to make a reference to company painting, you could make it here in a different sort of way because Nilima in her own way painted life around, you know. The lady who worked for us, you know, the homeopath we used to visit, you know, and so life of children in school, life of children in let’s say in Baroda or in Dalhousie, and I think in a way she also developed an idiom which I would associate to an extent with certain kind of Bengal school painting, especially Abanindranath Tagore. Abanindranath Tagore when he painted his Arabian Nights paintings was actually referring to streets down Jorasanko, the Tagore house where he lived. It was all those tradesmen, all those workers, all those sort of characters, you know, that were in the street, and in some way, though Nilima’s work is not dramatic, whereas Abanindranath’s work can be dramatic, she was referring to these things. I think to her credit, more than me, she got involved in actually using the technique of Indian miniature painting. She actually imbibed that, she learnt it. She made it a kind of a mission to know about it. She went to Nathdwara and learnt under Dwarkalal. She spent, you know, time on that. She went and saw Bannu in Jaipur, worked, you know, and learnt about how he painted, and in a way brought in her own work, which I think is rare, hardly any painter has ever done that, actually preparing the Vasli, that is the kind of mount that you make for painting, using the khadia, that is the whiting of which you make the first layer, then drawing and painting over and over, and then actually using the paper from Sanganer, that is from Rajasthan, handmade paper from Rajasthan, and also the idiom and the language, you know of... but obviously not using just one language, using multiple languages, and developing her own. I think for me it was a great companionship to my own concerns, and while I was studying Hamza and Hamzanama I was doing this and that, and she was going on very quietly working, you know, in this manner, I think which was a very, in a way also complimentary and a very fulfilling experience because we shared. We began to share everything literally. I mean she came to share Sienese painting partly because of my hang-ups and also in many paintings, you know, we discovered on our own all kinds of things. And even when I, I think she also made me to write more, to say what I was teaching, and often, you know, in my writings, particularly the English language writings, you know, we had great discussions, and often, you know, she helped me articulate my ideas.

Gulammohammed Sheikh is an Indian painter, writer and art critic who has been a major figure in the Indian art world for half a century. His artistic career is closely associated with the renowned MS University of Baroda in Gujarat where after gaining his Master's degree, Sheikh went on to teach in the Faculty of Fine Arts, and where he was appointed Professor of Painting in 1982.

Title: My wife and my children

Listeners: Timothy Hyman

Timothy Hyman is a graduate of Slade School of Fine Art, London, in which he has also taught. In 1980 and 1982, he was Visiting Professor in Baroda, India. Timothy Hyman has curated many significant art exhibitions and has published articles and monographs on both European and Indian artists.

Duration: 4 minutes, 44 seconds

Date story recorded: December 2008

Date story went live: 18 November 2010