NEXT STORY

Benode Bihari Mukherjee and KG Subramanyan

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Benode Bihari Mukherjee and KG Subramanyan

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 31. The effect of realism on my work and teaching | 63 | 01:03 | |

| 32. My wife and my children | 75 | 04:44 | |

| 33. Vrishchick and Lali Kala | 101 | 04:33 | |

| 34. Geeta Kapur and the Baroda school | 342 | 04:02 | |

| 35. The early '70s, artist’s camps and Place for People | 82 | 06:34 | |

| 36. Developing as artists and people | 58 | 04:46 | |

| 37. Pieter Bruegel and other artists | 42 | 02:50 | |

| 38. The 1975-77 state of emergency | 62 | 05:16 | |

| 39. Kabir | 43 | 06:46 | |

| 40. Benode Bihari Mukherjee and KG Subramanyan | 67 | 04:18 |

Kabir is taught in school, so our textbooks, Hindi textbooks, would have Kabir in it, all in Gujarati textbooks will have the saint poetry, like Mirabai, and we would have our own Gujarati Kabir called Akhor, and one would know about Kabir. I think most children in India, even today, would have heard of Kabir, because Kabir is also, you know, quoted. His poetry, particularly the couplets, you know, are like aphorisms. They are like proverbs at times, you know, people would recite it, and it is across – what shall I say – classes, across castes, across communities, people would remember it. Kabir himself was sort of a crossover. Now, he was not, nobody knew because they said that it was a child which was born of a Brahmin couple and which was reared by a Muslim family, and that when he died there was a quarrel whether to... bury him or cremate him, and that under his shroud there were only flowers. There are all kinds of legends about him, but the greatness of Kabir lies in two things to my mind. One is... the way he dealt with the sacred and the spiritual, he spoke in a very, you know, almost a language of the common people, ordinary people, and he was, you know, he could formulate an idea which would appear to be very simple, but it could be read in multiple ways. So it is almost kind of layered poetry, as you would say. I'll give you an example, that if he were to – let us say – write about hiraņa, which means a deer, which is an animal of prey, let’s say, you know, people hunt hiraņa. If you have the audience in front of whom suppose somebody like a musician... somebody like Kumar Ghandar, a great musician, who sang Kabir, were to sing that, there would be people who would take it as if it is an act of violence against animals. There would be people who would take it as if that hiraņa has something to do with some myth. It can be Ram, sort of chasing a demon. There would be another level at which it would be read as if it is the self, you know, which is being attacked. So, you know, there are beyond that, you know, they would have their own interpretation which I think Kabir allows, and that kind of layered poetry which has element of the, you know, I mean he in a way did not speak about any particular deity, although he used word Ram, and Ram was a generic character rather than Ram in the epic. But it would be something that he would say, ‘Tera saain tujh mein, jag sakey to jaag’. He said, 'Your, whatever... you know, what you are seeking yourself is within you. Awake if you can’. In that sense he actually allowed people to discover their own selves. So it hit very deeply and it went across both generations and times, and even today Kabir could be quoted. That is one.

Is that 15th century?

15th, 16th century, between that. But the other dimension of Kabir is very hard-hitting social poetry, and there he could really tear you down. You know, he wrote in a language which can be considered very hard and strong, but beautifully said. And so he sort of pounced upon hypocrisy, you know, especially religious hypocrisy. He also attacked pretence of different kinds and he even talked about the great gurus and those who are the big preachers, and he attacked both the priests of different – let us say – religious denominations. He would attack a Muslim priest and he would attack a Hindu priest. You know, he... so in way he was carving a new kind of belief system which was multiple. You know, we could bring together all the... and also innate wisdom of the land. I think there is something which people have in them, and since he was a weaver, he wrote his poetry using the metaphor of weaving, warp and weft, and in fact, quite a number of things he talks about is about warp and weft and I think these images and these metaphors hit, you know, the, you know, particularly the oppressed, you know. So I am not surprised that Kabir continues to appeal to audiences, not only in North India, those who speak Hindi, but also in many other regions where there are sort of different Kabirs who have emerged in different languages.

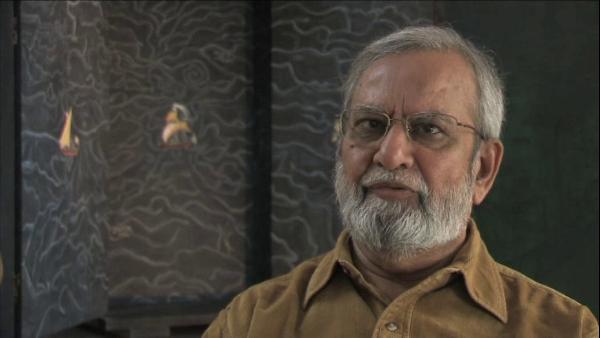

Gulammohammed Sheikh is an Indian painter, writer and art critic who has been a major figure in the Indian art world for half a century. His artistic career is closely associated with the renowned MS University of Baroda in Gujarat where after gaining his Master's degree, Sheikh went on to teach in the Faculty of Fine Arts, and where he was appointed Professor of Painting in 1982.

Title: Kabir

Listeners: Timothy Hyman

Timothy Hyman is a graduate of Slade School of Fine Art, London, in which he has also taught. In 1980 and 1982, he was Visiting Professor in Baroda, India. Timothy Hyman has curated many significant art exhibitions and has published articles and monographs on both European and Indian artists.

Duration: 6 minutes, 46 seconds

Date story recorded: December 2008

Date story went live: 18 November 2010