NEXT STORY

The 1975-77 state of emergency

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The 1975-77 state of emergency

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 31. The effect of realism on my work and teaching | 63 | 01:03 | |

| 32. My wife and my children | 75 | 04:44 | |

| 33. Vrishchick and Lali Kala | 101 | 04:33 | |

| 34. Geeta Kapur and the Baroda school | 342 | 04:02 | |

| 35. The early '70s, artist’s camps and Place for People | 82 | 06:34 | |

| 36. Developing as artists and people | 58 | 04:46 | |

| 37. Pieter Bruegel and other artists | 42 | 02:50 | |

| 38. The 1975-77 state of emergency | 62 | 05:16 | |

| 39. Kabir | 43 | 06:46 | |

| 40. Benode Bihari Mukherjee and KG Subramanyan | 67 | 04:18 |

Well, it is, I mean Bruegel is an artist I am interested in, but I am interested in particular aspects of Bruegel. I think it is the linguistic terms. I am curious about the way he distorts his figures. You know, when you have a kind of a naturalistic language and you sort, kind of have a character, you know, or characters in whom you have kind of reposed certain elements, you know. You have something like a funny man or a slightly evil character or something peculiar, I think that is what interested me. I’m... of course I am a great admirer of his work, but at a personal level I can only say that, but I think at one level I also got involved in Grosz, George Grosz, and I think the city paintings took me. Initially it was Sienese, no, it was Ambrogio Lorenzetti, which I had greatly admired and which I had discovered while I was a student. In fact, my teacher, Amberkar had helped me in that because I used to respond to that, and he told me about those, and then when I saw them, you know, in reality, I was very deeply, greatly moved, and I realised that there was something very common in my view of looking and painting in movement. Not from a still, one single point of view, but multiple views. You know, you paint as if you are walking in a street. And so Ambrogio’s painting actually deals with that. Actually, you go through the street with him, and the street opens up as you walk and there is a physical walk also. So this brought me back to Ajanta, which is again about walking. This in a way brought me to Hamzanama in which you actually, you know, don’t physically walk, but your eye walks through, and I think Mughal painting, a lot of Mughal painting is about walking, about discovering, and the landscape rises up as you walk, as you go up. So, all these things were sort of in a way, you know, coalescing and coming together, and this is the time then I think with Kasauli, with friends, little groups meeting at home, it finally got sort of, you know, connected with that and that is how the whole thing came about.

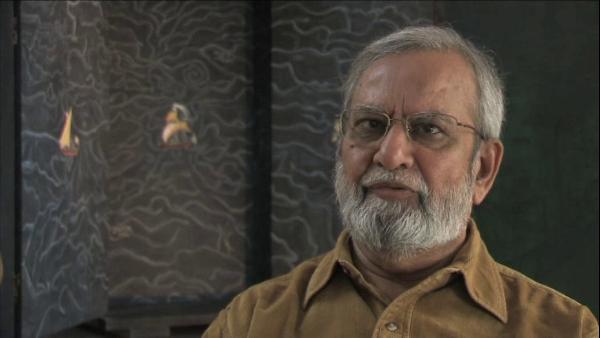

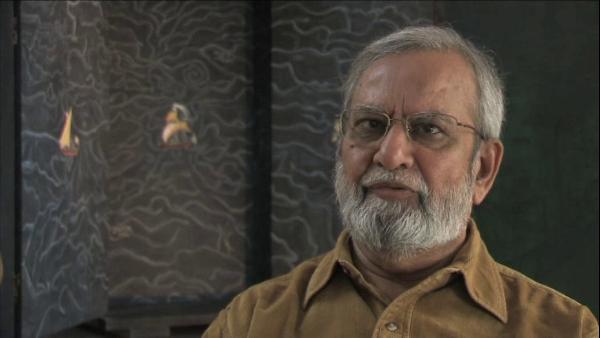

Gulammohammed Sheikh is an Indian painter, writer and art critic who has been a major figure in the Indian art world for half a century. His artistic career is closely associated with the renowned MS University of Baroda in Gujarat where after gaining his Master's degree, Sheikh went on to teach in the Faculty of Fine Arts, and where he was appointed Professor of Painting in 1982.

Title: Pieter Bruegel and other artists

Listeners: Timothy Hyman

Timothy Hyman is a graduate of Slade School of Fine Art, London, in which he has also taught. In 1980 and 1982, he was Visiting Professor in Baroda, India. Timothy Hyman has curated many significant art exhibitions and has published articles and monographs on both European and Indian artists.

Duration: 2 minutes, 50 seconds

Date story recorded: December 2008

Date story went live: 18 November 2010