NEXT STORY

The peepshow man

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The peepshow man

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 51. Figures in my work | 38 | 01:40 | |

| 52. The commission at Bhopal | 39 | 09:20 | |

| 53. Using computers for my work and mappa mundi | 61 | 09:43 | |

| 54. The story of books | 35 | 06:48 | |

| 55. The peepshow man | 26 | 03:43 | |

| 56. Travelling Shrine – Home (Part 1) | 39 | 07:01 | |

| 57. Travelling Shrine – Home (Part 2) | 30 | 09:07 | |

| 58. More about my family (Part 1) | 30 | 02:18 | |

| 59. More about my family (Part 2) | 30 | 06:29 | |

| 60. Differences between Surendranagar and my life now | 32 | 06:49 |

Just around the time I finished a mural I was in the process of... sort of, looking for another way, another medium, another format to sort of bring in the stories of journeys. So I got a book bound in an accordion format, this was I think, ’96, I think the same year that I finished the mural. And I used to ask people which I was familiar with because I had already done some water colours and that, and I began to draw in this book. And I thought that I would draw all pages, big, small book, you know, roughly about a foot and... 10 inches, I could carry it with me wherever I go. So it has become a book of journeys of sort. I carried it wherever I went for almost 10 years. I carried it to Italy where I had a residency in Civitella Ranieri. I carried it lastly to Montalvo in California and in India when if I went to Delhi and stayed there for a few days, I would paint something. So in a way it is a story of, in some ways, my own ideas and my concerns, but at the same time the times in which I lived. Like the new house that I had come to live in here, but soon after that we also encountered that there was this, what shall we call it, it is called India sort of tried its nuclear device. It was, I think... something you know which is, which I’m unable to come to terms with, you know, an atomic state. So there are paintings, there are drawings in which I have packed my bags and there is Pokhran, you know, where this kind of, you know, test took place in Rajasthan. To moving along and then Kabir became a kind of an image, you know, which I wanted to paint. I had not painted Kabir but I thought that if somebody can sing Kabir why I can’t paint it, you know. It is in that way that I started and there is an image of Kabir in that. Then there are images which come from Pietro Lorenzetti, from his Deposition and images which relate to Italian landscape – something which I saw there while I was in Churta and I painted about 16 paintings there while I stayed there for about 6 weeks – and it went on like that.

At the time when I... in the 4 years time when I was exposed to digital I thought why not try it digitally, too, and I did two books, one on Kashmir, it’s called ‘Whose Kashmir’ and I brought in images from different sets of paintings, mostly quotations. And another I did on churning, we call it Samudramanthan, ‘Churning of the Ocean’ and I used the image from Angkor Wat, you know, where there is a great relief about the churning of the ocean myth. I used it in a modern context because here from the churning comes out Hiroshima, both Hitler and Gandhi come out from that, etc. Then my friend Bupan died in 2003 so I did a book in memory of Bupan. And here I would connect it with my present preoccupation – that I had wanted to do something on the belief systems, but I had not found either a format or a way by which one could deal with it. Kabir was, in a way, you know, it had paved the way, not as a process, in which you could use Kabir or Kabir’s ideas or Kabir’s poetry. And I did a series of paintings on Kabir. But I was still looking for something, you know, which I thought would perhaps serve the basis of a kind of a - what would you call it? It would be secular yet it would still be spiritual. And I had seen this, what is called, Kaavad made in Rajasthan. These are boxes, wooden boxes and they have multiple doors, they open in four directions and these are all... then could be folded up. It had images of gods and goddesses and sometimes from the epics, but usually gods and goddesses. And the box would have an inner sanctum of sorts where they would put little wooden images also. The narrator carries on his body and he moves from place to place and he performs. I was quite fascinated by this idea and when I saw a big or this Kaavad, which means a kind of travelling shrine or a moveable, mobile shrine, I thought, well, could one do that? So I embarked upon that. Having done the book it became a kind of a passage, you know. Books served to be a passage towards this, the actual physical thing. The book was something you could open and you would have multiple combinations of images. Here the shrine also is kind of a book, you know, which can be opened and closed but it is a shrine which is a personal shrine. So you can open it in whichever direction you want to, whichever combination you wish to make, and you can then close it and it becomes a small box.

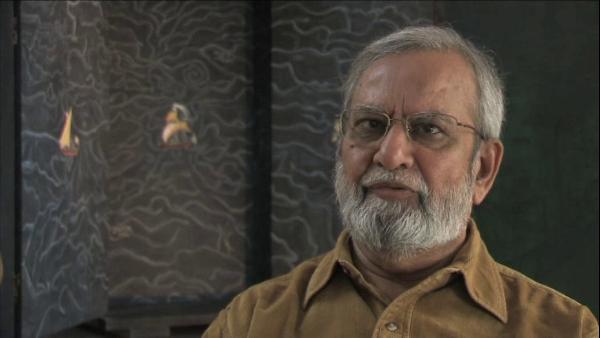

Gulammohammed Sheikh is an Indian painter, writer and art critic who has been a major figure in the Indian art world for half a century. His artistic career is closely associated with the renowned MS University of Baroda in Gujarat where after gaining his Master's degree, Sheikh went on to teach in the Faculty of Fine Arts, and where he was appointed Professor of Painting in 1982.

Title: The story of books

Listeners: Timothy Hyman

Timothy Hyman is a graduate of Slade School of Fine Art, London, in which he has also taught. In 1980 and 1982, he was Visiting Professor in Baroda, India. Timothy Hyman has curated many significant art exhibitions and has published articles and monographs on both European and Indian artists.

Duration: 6 minutes, 48 seconds

Date story recorded: December 2008

Date story went live: 18 November 2010