NEXT STORY

Differences between Surendranagar and my life now

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Differences between Surendranagar and my life now

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 51. Figures in my work | 38 | 01:40 | |

| 52. The commission at Bhopal | 39 | 09:20 | |

| 53. Using computers for my work and mappa mundi | 61 | 09:43 | |

| 54. The story of books | 35 | 06:48 | |

| 55. The peepshow man | 26 | 03:43 | |

| 56. Travelling Shrine – Home (Part 1) | 39 | 07:01 | |

| 57. Travelling Shrine – Home (Part 2) | 30 | 09:07 | |

| 58. More about my family (Part 1) | 30 | 02:18 | |

| 59. More about my family (Part 2) | 30 | 06:29 | |

| 60. Differences between Surendranagar and my life now | 32 | 06:49 |

My father died, I think, around the time, before I went to England, but he was not an unhappy man at that point of time. He was happy that I went to study in Baroda. So, it is not associated with unhappiness of any kind, and at that time the other brothers had already secured jobs. That is something which he had wished, and they also had children. So, in a way they were – as we say in Gujarati – thale padi gaya, they are all settled. So there was a settled family and well, there were conflicts, you know, that brothers would not agree with each other and all that, but that is part of a long story. But it was not so pronounced that one would consider it to be a main issue, because it was generally that they lived their own life. One brother became a postmaster. The other brother was in what we call administrative service, that is, in the office of the collector, and he also rose in position. The third brother began with a postman, but then he also rose in position and he just died, recently. And my sister who lived in another town, she was the only one left among those. The story goes that she couldn’t bear the loss of her brother, that brother, and she passed away within a month after brother died.

So they are all buried there in that, you know, in different towns, in Kathiawad near Surendranagar, and the family, the children, now it is almost a family of a hundred or more. Luckily they are educating their children, and even girls are educated. The problem is that because of communalism, which is particularly faced by young Muslim boys who often find it difficult to get jobs because of discrimination, either give up studies or opt for something, you know, which is like, you know, starting a small business or running even sometimes rickshaw or trucks, or become mechanics, things like that, which has introduced a kind of a regressive... process of de-education that after being educated they are going into a profession where this education is not required, and its effects are felt upon women, children, particularly girl children. So girls... to educate girls would mean they would have to go to the house of a groom who is not educated. So it’s a big issue, it’s a problem, you know, that often girls are not educated, or educated up to a point, and I think this is the case with quite a lot of Muslim families. This, many people don’t realise, it is an issue, but it is a very important issue because with absence of education, the community would not go out, and as I mentioned earlier that, you know, on its own, community doesn’t come out because it has no economic means. And there is no leadership within the community, there is no enlightened leadership, and hence they still remain at the same social political level where I think except for vote bank, you know, when different parties woo them, there is no hope, you know. At times one feels quite disheartened.

But I have seen of late that earlier even the boys were not being educated, but now they have found that IT, that is information technology, seems to be very open. And so that kind of a discrimination we had noticed in jobs and in education has been sort of now replaced by this kind of an open-armed...

Technological.

Yah, so some of the boys have got into that. One of them is, you know in, I think he went to Saudi Arabia, he had been to Germany and he had studied in Bangalore. So these are the grandchildren now, and I hope that that will also initiate the process of girl child being educated, because they are now educated. In my family two girls had education, one because she couldn’t marry because she had leukoderma, and another one who was divorced, and hence she had nothing to do so she got educated. Ironic, very strange, peculiar situation, and luckily now she has found a groom who is educated. So there are a few. The family remains there and they are sort of in a way, their life is there, you know.

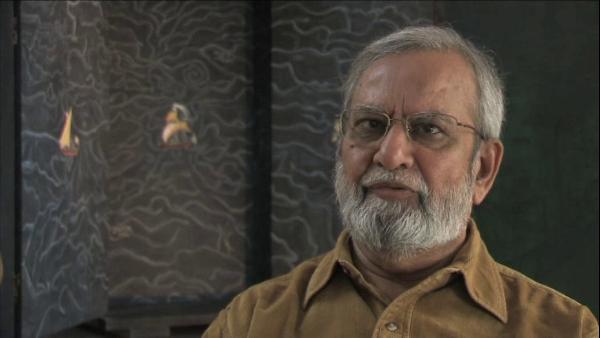

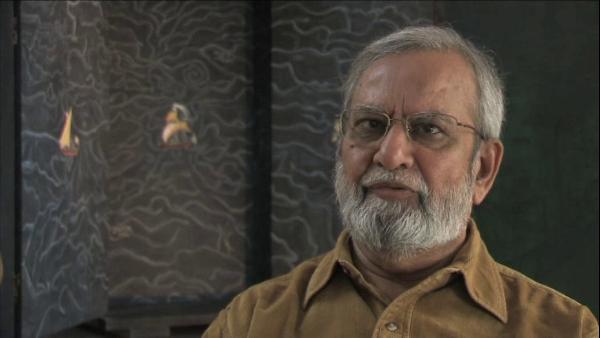

Gulammohammed Sheikh is an Indian painter, writer and art critic who has been a major figure in the Indian art world for half a century. His artistic career is closely associated with the renowned MS University of Baroda in Gujarat where after gaining his Master's degree, Sheikh went on to teach in the Faculty of Fine Arts, and where he was appointed Professor of Painting in 1982.

Title: More about my family (Part 2)

Listeners: Timothy Hyman

Timothy Hyman is a graduate of Slade School of Fine Art, London, in which he has also taught. In 1980 and 1982, he was Visiting Professor in Baroda, India. Timothy Hyman has curated many significant art exhibitions and has published articles and monographs on both European and Indian artists.

Duration: 6 minutes, 29 seconds

Date story recorded: December 2008

Date story went live: 18 November 2010