NEXT STORY

Moments of change and making friends (Part 2)

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Moments of change and making friends (Part 2)

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 61. Moments of change and making friends (Part 1) | 28 | 05:36 | |

| 62. Moments of change and making friends (Part 2) | 18 | 06:49 | |

| 63. Curating | 26 | 04:34 | |

| 64. Home Street Shrine Bazaar Museum | 45 | 09:52 | |

| 65. Benode Bihari Mukherjee (Part 1) | 42 | 05:47 | |

| 66. Benode Bihari Mukherjee (Part 2) | 28 | 05:24 | |

| 67. Fitting it all in | 18 | 03:33 | |

| 68. Bhupen Khakhar’s sexuality | 110 | 04:37 | |

| 69. Politics and rivalry | 42 | 08:29 | |

| 70. My monograph and writings on art | 40 | 02:28 |

Strangely enough don’t think there was such a crisis that should have a, created a great impact on my mind. In other words, it’s not that there was no crisis or there was no conflict. There were points at which, you know, one felt that, you know, you entered in a different kind of life experience. You know, it was world changed, you know. For me, simply to come to Baroda was a change. I made that change in my life. I have never anticipated that. I didn’t know what I was entering. But that did not again sever my links with Surendranagar. The second was going to England, you know, to London for 3 years, and it was again quite a tremendous experience, you know. An entirely different world and one also came in contact with something which one had read about in either literature or learnt from, you know, people you had met. But to be there, you know, was quite an experience at times, but even from a, but it didn’t really, didn’t really change my world view.

I mean, living in the western world is an experience which many people who have grown up in the east, you know, would find it traumatic at times because the way relationships are formed in India, you know, like living in a joint family, you know, are very different than the way the families and others function there. You know, there is, in a way there is a separation between, you know, there is... relationship is seen in terms of individuals and each individual has his freedom, and I think children after they have finished their school, they become independent. So there is a relationship, and in India we have perhaps in some ways much greater emotional bonds, and if it is a joint family, that bond is even greater, and perhaps, you know, that kind of a bond is something which may create problems for those who wish to live an independent life, you know. I noticed that. I mean I was observing all this thing, you know. I do remember that, you know, when you are abroad and living on your own... once, I think it was during Christmas when everybody goes home, despite the fact that it’s a liberal and very secular world, Christmas is a major kind of a festival and it was a family bond. Everybody would go there, and then you suddenly realise that, oh, it’s different, it’s not like what you thought that people do not have that kind.... But that is the point where you even find that you are isolated, you know, and I think it’s quite possible that even now people... but it all depends upon what kind of friends you have, you know, and the friends can even take you home. But I did realise that that was something very personal, people would like to go home themselves rather than carry their friends with them. But anyway, that can be different. I had some wonderful friends there. I made friends with my classmates... and I used to, I think they must have found me very nosey because I used to barge into studios of other students, which was not known because they would not do so. I was very curious as to how they lived, what they did, why, where did they come from. Like this was a British lawyer who came from a very, I think... how shall you put it... a sophisticated, perhaps well-to-do family. He would be impeccably dressed and he would have his apron on him and he would put it away and then he would not even come for lunches with us in the common room or come to view there, but go to some place where he would have his whatever, the kind of lunch that he would have, his pie and perhaps he would have his wine and all that. I was very curious. I became very friendly with him. I forced him to... and in fact I went to his place also. We went brass-rubbing in the country and things like that because I wanted to know what it was, you know, to be, you know, in a family like that. I think his parents found me rather strange, but they couldn’t do anything because I had already converted this boy into a good friend and we both went into [the] country and did that. Anthony Mannering was his name. I don’t know, he was not much of a painter, but I don’t know what he did later.

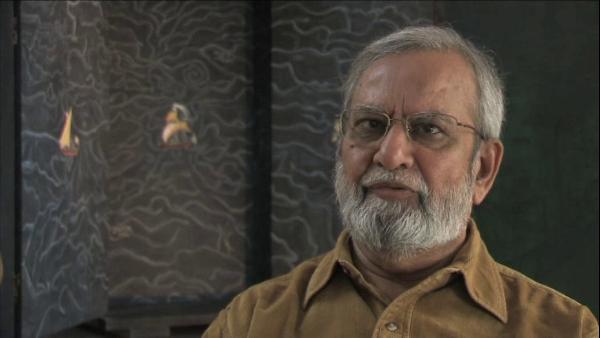

Gulammohammed Sheikh is an Indian painter, writer and art critic who has been a major figure in the Indian art world for half a century. His artistic career is closely associated with the renowned MS University of Baroda in Gujarat where after gaining his Master's degree, Sheikh went on to teach in the Faculty of Fine Arts, and where he was appointed Professor of Painting in 1982.

Title: Moments of change and making friends (Part 1)

Listeners: Timothy Hyman

Timothy Hyman is a graduate of Slade School of Fine Art, London, in which he has also taught. In 1980 and 1982, he was Visiting Professor in Baroda, India. Timothy Hyman has curated many significant art exhibitions and has published articles and monographs on both European and Indian artists.

Duration: 5 minutes, 36 seconds

Date story recorded: December 2008

Date story went live: 18 November 2010