NEXT STORY

Why can't machines do things that babies can?

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Why can't machines do things that babies can?

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 61. Developing programs that could understand written questions | 2252 | 02:22 | |

| 62. AI programs 'devolving' from calculus to geometry | 2377 | 03:11 | |

| 63. Why can't machines do things that babies can? | 2314 | 03:39 | |

| 64. Facial recognition machines | 2043 | 01:13 | |

| 65. How computers developed at MIT | 2679 | 02:55 | |

| 66. The conflict between AI research and computer science | 2649 | 01:58 | |

| 67. What I think is wrong with modern research | 2774 | 02:32 | |

| 68. Lowell Wood's novel idea for launching a space station | 2503 | 03:37 | |

| 69. The importance of my undergraduate classes at Harvard | 2640 | 01:26 | |

| 70. My undergraduate thesis in fixed point theorems | 3638 | 04:26 |

And in the 1960s, from beginning in 1958, there were several such programs that showed… the most dramatic one was one that was good at formal... the part of formal mathematics called integral calculus and a young student named James Slagle wrote a program that was better than most students at doing what was called integration which was a process invented by Isaac Newton and had been developed for several hundred years, but it was... never been automated before this time. And a graduate student named Joel Moses, who eventually became Provost of MIT, and... very important post in the faculty, but that was his project. Well, James Slagle was the... the first one to do it and interesting thing about Slagle was that he was blind but by using a programming language invented by John McCarthy called Lisp – it’s a sort of joke, well, it’s short for list processor – and this was a very high level computing language which could do rather complicated things with fairly brief expressions.

Joel Moses, who was the student who followed Slagle, said it took him a couple of months to understand the ten pages of text that the blind Slagle had written to... to do this, because this language was so compact and expressive. So that’s a nice story in itself and maybe we should get Joel Moses to tell it. But anyway, this meant that in the early 1960s, for several years… I mean, 1970s, we had made a lot of progress from calculus which is... which was at that time generally a subject in college to algebra – mathematics – which is a kind of high school subject and getting down to elementary geometry, proving theorems which was a pre-high school subject or some cases. And so this was an interesting period of five or... five or 10 years in which evolution seemed to be going backwards.

Most people didn’t understand why would it be easier to write a calculus program than a geometry program? The answer is: you had to know more about the world; you had to know more different things for the subjects that people considered easier, but they were easier because they’re part of real life and people experience geometry but they don’t experience acceleration in... in the sensible way.

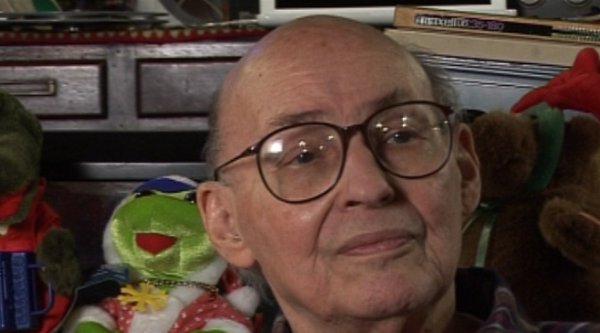

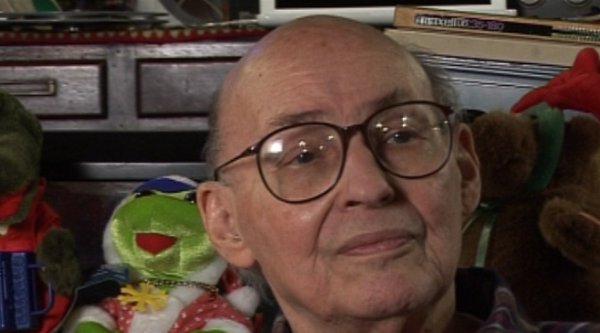

Marvin Minsky (1927-2016) was one of the pioneers of the field of Artificial Intelligence, founding the MIT AI lab in 1970. He also made many contributions to the fields of mathematics, cognitive psychology, robotics, optics and computational linguistics. Since the 1950s, he had been attempting to define and explain human cognition, the ideas of which can be found in his two books, The Emotion Machine and The Society of Mind. His many inventions include the first confocal scanning microscope, the first neural network simulator (SNARC) and the first LOGO 'turtle'.

Title: AI programs 'devolving' from calculus to geometry

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: 1960s, 1958, Lisp, MIT, James Slagle, Isaac Newton, Joel Moses, John McCarthy

Duration: 3 minutes, 12 seconds

Date story recorded: 29-31 Jan 2011

Date story went live: 12 May 2011