NEXT STORY

Facial recognition machines

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Facial recognition machines

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 61. Developing programs that could understand written questions | 2252 | 02:22 | |

| 62. AI programs 'devolving' from calculus to geometry | 2376 | 03:11 | |

| 63. Why can't machines do things that babies can? | 2314 | 03:39 | |

| 64. Facial recognition machines | 2043 | 01:13 | |

| 65. How computers developed at MIT | 2679 | 02:55 | |

| 66. The conflict between AI research and computer science | 2649 | 01:58 | |

| 67. What I think is wrong with modern research | 2774 | 02:32 | |

| 68. Lowell Wood's novel idea for launching a space station | 2503 | 03:37 | |

| 69. The importance of my undergraduate classes at Harvard | 2639 | 01:26 | |

| 70. My undergraduate thesis in fixed point theorems | 3638 | 04:26 |

So there was a... interesting decade in which artificial intelligence started with very advanced things that most people considered hard and difficult, but weren’t. And we’re still not at the stage – this is 60 years later, 50 years later, anyway – there’s no machine that in any deep sense understands why you can pull something with a string but not push it. And of course the answer is that, once the string is straight it can't... its length can’t change so the object has to follow it or the string breaks. But it you go this way the length can change because the thing can curl up and it doesn’t take any force to push a loop and every child – every normal child – understands that sort of thing very well. But to this day no computer that I know of, no program understands that much about elementary manoeuvring in the real world.

One problem in the progress of artificial intelligence is that most researchers got stuck with this sort of problem; they tried to build robots that could do everyday things. So here you have this strange situation where, in 1961... robots, or rather computers, can solve mathematical problems that only very advanced students can do. Now if you look around the world you see robots trying to solve problems that every baby can... that four-year-olds, three-year-olds can speak a lot of language; they can build houses with blocks… we don’t have any robots that are... have the kind of general physical competence that a two or three-year-old has and I think the joke is that if those researchers would simulate the robots with stick figures instead of building actual physical ones with motors, progress would be much faster. Because if you have a simulated robot then one computer can support 20 students trying different experiments with it because a typical computer today could have as many as 50 or 100 different terminals with… because the computers are all time shared today and they can serve dozens or hundreds of customers.

If you build a physical robot in a laboratory... if you visit a robotics laboratory you’ll find that there’s usually one or two of the latest machine, it’s only working three hours out of every 24; it’s usually broken or someone’s improving it. So only one student at a time is doing some experiment that takes six weeks instead of five minutes, but people feel it’s not real if it’s just a picture of the robot, I think they’ve… it’s a community that has sort of strayed by mistaking certain... one kind of reality for another. It’s a... it's an interesting thing, that they don’t see the cost of confining yourself to a non-time-shared machine.

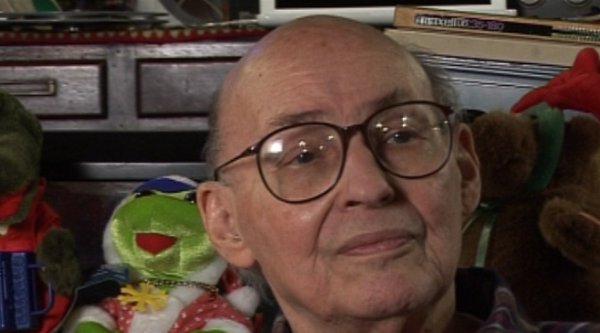

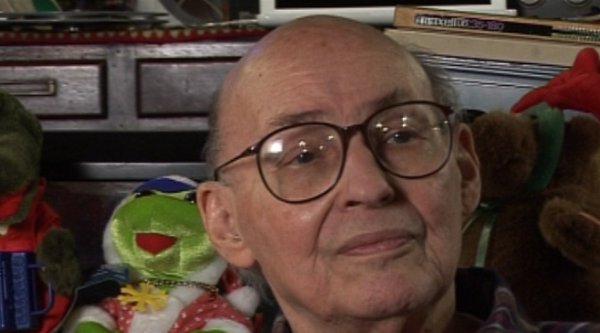

Marvin Minsky (1927-2016) was one of the pioneers of the field of Artificial Intelligence, founding the MIT AI lab in 1970. He also made many contributions to the fields of mathematics, cognitive psychology, robotics, optics and computational linguistics. Since the 1950s, he had been attempting to define and explain human cognition, the ideas of which can be found in his two books, The Emotion Machine and The Society of Mind. His many inventions include the first confocal scanning microscope, the first neural network simulator (SNARC) and the first LOGO 'turtle'.

Title: Why can't machines do things that babies can?

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: 1961

Duration: 3 minutes, 40 seconds

Date story recorded: 29-31 Jan 2011

Date story went live: 12 May 2011