NEXT STORY

Chomsky's theories of language were irrelevant

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Chomsky's theories of language were irrelevant

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 81. The beginning of cognitive psychology | 2474 | 01:17 | |

| 82. The strange history of neuroscience | 2518 | 03:34 | |

| 83. Chomsky's theories of language were irrelevant | 1 | 2925 | 02:28 |

| 84. Losing students to lucrative careers | 2225 | 02:23 | |

| 85. Psychology should not be like physics | 2063 | 04:07 | |

| 86. Seymour Papert goes in a different direction | 1871 | 01:23 | |

| 87. Seymour Papert's little scientists | 1809 | 02:23 | |

| 88. Representations of the mind, knowledge and thinking | 1838 | 01:51 | |

| 89. Producing The Society of Mind | 1809 | 03:13 | |

| 90. The Emotion Machine | 1743 | 01:43 |

Some troubles appeared and the picture of this wonderfully developing science, it was called cybernetics in the late 1940s, the idea of machines that had... that behaved as though they had goals and purposes to some small extent and all sorts of mathematical theories of that and how that might be used for machines. In the 1970s we had made progress on getting machines to understand the meanings of some words and sentences and a certain amount of linguistics. But strangely, by the 1980s, a lot of institutions that thought that they were working on new advanced theories of psychology, seemed to be going backwards and looking for theories of thinking that were more like Newton’s laws, going back, can I find three principles to guide learning, rather than three or four hundred.

If you look at the... what we know about the function of the human brain, and my favorite example is to take a big book on neurology and look at the index, you’ll find the names of maybe 200 or more different parts of the brain that have been identified, at least for the present, as being involved with slightly different or grossly different functions, so... some parts are clearly involved with language and others are clearly involved with vision and hearing and different sensory systems, some parts are involved with planning ahead for motor activities and so forth. And we know that you don’t want to describe what the brain does by anything like three laws or seven laws, because that wouldn’t account for why there are more than 100 different... different kinds of computations going on in the brain.

I have a lot of friends in neuroscience who say: 'Oh, don’t worry about that, there’s a lot of evidence that all of the different areas of the brain are basically very similar, they have almost the same structure, they’re just in different places and just connected to different things.' And, yes, you could say that. You could say all people are almost the same, because they’re all between four and eight feet high and they all weigh between 50 and 500 lbs and there’s very few differences. So it makes me nervous to see neuroscience moving in the direction of saying: 'Look, all the different parts of the brain, they’re all made of the same kinds of cells – neurons – maybe axon... maybe neuro... glial cells and so forth. So you know, in fact there’s a very popular theory that says almost all parts of the brain are practically the same and I don’t want to go into that.

But it’s clearly to me, what you want is to elaborate theories of the differences. Why are some people so much better at some things than others and can you correlate that with small differences between parts of the brain, not... not saying: 'Oh, they... they must all be doing virtually the same thing.' Maybe they are, but it’s the differences that matter.

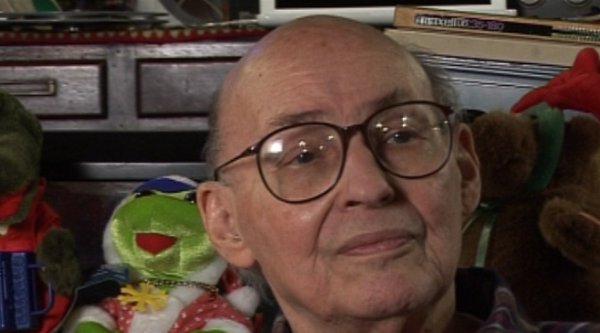

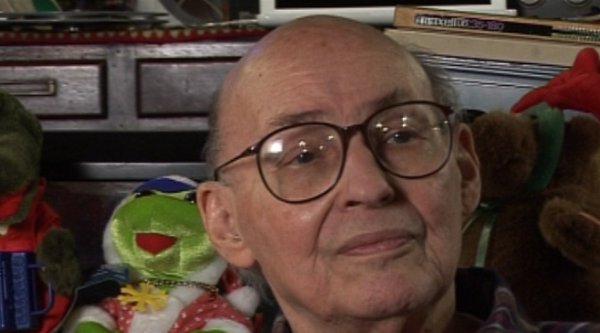

Marvin Minsky (1927-2016) was one of the pioneers of the field of Artificial Intelligence, founding the MIT AI lab in 1970. He also made many contributions to the fields of mathematics, cognitive psychology, robotics, optics and computational linguistics. Since the 1950s, he had been attempting to define and explain human cognition, the ideas of which can be found in his two books, The Emotion Machine and The Society of Mind. His many inventions include the first confocal scanning microscope, the first neural network simulator (SNARC) and the first LOGO 'turtle'.

Title: The strange history of neuroscience

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: 1940s, cybernetics, 1970s, 1980s, Isaac Newton

Duration: 3 minutes, 35 seconds

Date story recorded: 29-31 Jan 2011

Date story went live: 12 May 2011