NEXT STORY

The difference between information, knowledge and wisdom

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The difference between information, knowledge and wisdom

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41. The philosophy of surgery | 261 | 04:24 | |

| 42. Judgement as the ultimate tool of a physician | 206 | 04:01 | |

| 43. The art of keeping yourself calm | 1 | 261 | 05:12 |

| 44. Surgery is fun! | 200 | 04:09 | |

| 45. Devouring medical literature | 186 | 03:54 | |

| 46. Averill Liebow and the best compliment I've ever had | 246 | 05:37 | |

| 47. The difference between information, knowledge and wisdom | 241 | 04:45 | |

| 48. The importance of being curious | 203 | 04:44 | |

| 49. 'Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a great battle' | 1 | 270 | 03:22 |

| 50. Percy Shelley's moral imagination | 207 | 04:34 |

In surgery, you impress people by your judgement and by your steadiness.

And one of the greatest compliments I used to get, which I got from people in academic internal medicine, was this guy is a medically-oriented surgeon. In other words, I was less quick to operate than a lot of my colleagues, that I followed my patients very, very, very carefully and attended to the physiological needs of their bodies in addition, I like to think, of their souls.

I could go to medical grand rounds and talk with some knowledge of the things the medical people were more interested in than the surgeons were, and I can actually elucidate this by something that happened to me when I was a fellow in the laboratory. My fellowship was right after the internship. I took a year of fellowship in cardiac surgery. And I had to learn. I was working on certain aspects of the major circulation of the veins into the heart and congenital abnormalities. And I had to learn a technique called differential bronchospirometry, which is something where you put a tube down the windpipe and extensions of that tube… one goes into the bronchus, the trunk of the right lung, and one goes into the bronchus or the trunk of the other, and you take gas samples, expiratory samples, from each side. And it's a very difficult thing to do. You've got to, you know, do it just right, and so my chief, Bill Glenn, sent me over to the pathology department, where Professor Averill Liebow was using the technique. He had essentially invented it, and wouldn't let anybody learn it, because it was his baby. Well, so I go down to the pathology research lab, and the door, of course, is locked. That's how secretive all this stuff was. Liebow was a very small man. He was about 5'5” in height, the absolute obverse of his brilliance, because he was a man who would look at the photographs of the class the day before the first lecture and know everybody's name and make a comment on it.

For example, there was a fellow in my class whose name was James Miles, and he came in a little late, and as he walked into the pathology amphitheatre, Averill Liebow said, 'Oh, here comes Jim, Miles from home'. Jim Miles. And he kept calling one of the fellows Red. He called him Red. Nobody could understand, because Bob Nodine, he wasn't red at all. I mean, he didn't have red hair. Turned out his wife had blazing red hair. And how did Averill Liebow find out? But Averill knew everything, and talk about meticulous surgery, he was a meticulous pathologist. One of my colleagues, you know, Honest Abe the Log-Splitter, as they say about Lincoln, this was Averill Liebow: Honest Ave, the Hair-Splitter, was what he said about him. But in any event, Averill Liebow hated surgeons. He thought they were primitive. It seems they were always stealing his research, and this was essentially what I was trying to do: I was going to learn bronchospirometry. So I go down to the lab and knock on a locked door, and after about half a minute, which was a pretty long time to be standing there - I'm nervous already about entering, invading this laboratory - I hear the click of the lock and the door is slightly opened by the diener, the guy who runs the lab. He's not a physician, you know, he sets up the animals and sees that everything goes well, takes care of the equipment. And I knew the diener pretty well, because I'd had some doings with him. He was a very pleasant, good guy. And he opens the door just a little bit. And I look past him, and I see, about four operating tables away from me, is Dr Liebow, little Dr Liebow, operating on a dog, standing on a stool with his head just over the dog's chest. And he looks at me and he see who it is, and he says to the diener, he says, 'Oh, it's Nuland. He's a little less Neanderthal than most surgeons. Let him in'.

Of all the years of surgery, I think that was the greatest compliment I ever got from anybody. So I went in and I learned how to do this technique, and in later months, published an important paper, from our point of view, based on the use of differential bronchospirometry.

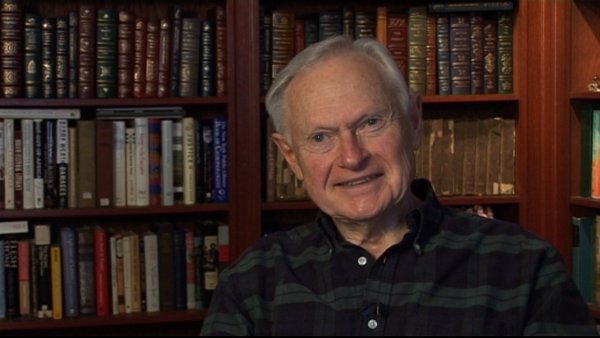

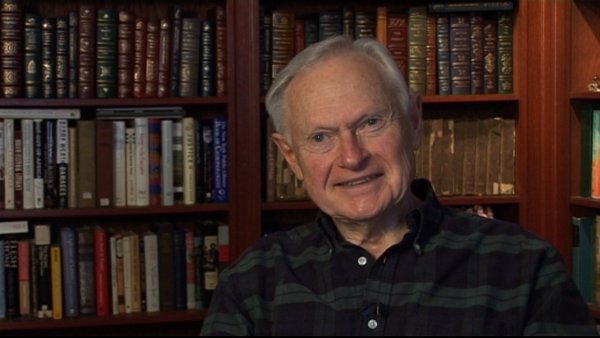

Sherwin Nuland (1930-2014) was an American surgeon and author who taught bioethics, the history of medicine, and medicine at the Yale University School of Medicine. He wrote the book How We Die which made The New York Times bestseller list and won the National Book Award. He also wrote about his own painful coming of age as a son of immigrants in Lost in America: A Journey with My Father. He used to write for The New Yorker, The New York Times, Time, and the New York Review of Books.

Title: Averill Liebow and the best compliment I've ever had

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: Averill Liebow, James Miles

Duration: 5 minutes, 37 seconds

Date story recorded: January 2011

Date story went live: 04 November 2011