NEXT STORY

The importance of being curious

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The importance of being curious

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41. The philosophy of surgery | 261 | 04:24 | |

| 42. Judgement as the ultimate tool of a physician | 206 | 04:01 | |

| 43. The art of keeping yourself calm | 1 | 261 | 05:12 |

| 44. Surgery is fun! | 200 | 04:09 | |

| 45. Devouring medical literature | 186 | 03:54 | |

| 46. Averill Liebow and the best compliment I've ever had | 246 | 05:37 | |

| 47. The difference between information, knowledge and wisdom | 241 | 04:45 | |

| 48. The importance of being curious | 203 | 04:44 | |

| 49. 'Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a great battle' | 1 | 270 | 03:22 |

| 50. Percy Shelley's moral imagination | 207 | 04:34 |

Again, to get back to the change that was occurring in me: I developed this ravaging appetite for history, for culture. I would even try to memorize dates, which I got pretty good at, because I could fix things in my mind if I knew the date relationships. It wasn't a question of just knowing the dates. You know, it didn't help me that Constantinople fell in 1453, per se, but when you add this to something like 1492, when Jews were thrown out of Spain, or 1588, when the Armada went down the drain or 1519, when Leonardo da Vinci died, these become indices on which you can hang the important pieces of knowledge that you know. And it was about that time, again, I'm in my late 50s or so, about that time that I began to discern the difference between information, knowledge and wisdom. Information is the facts. Knowledge is using those facts and putting them in a framework so that you understand the arena in which you're thinking. Now wisdom comes from the evolution of one's judgement, the evolution of one's experience, to take the knowledge and try to figure out what it means. And try to figure out how you can use it in everyday experience, or figure out how you can use it in your interpretation of history. This, to me, is wisdom. So when people say, well, you know, you become wise as you become old, the only advantage of age is, of course, you have more opportunity to have experience. You have more opportunity to read, you have more opportunity to talk to people, and around that time was when I became a big talker. One-on-one, usually not coffee, because I don't like to drink coffee during the day. It would be lunch, it would be just dropping into someone's office, or them dropping into whatever I was doing, and I developed a group of friends, six or seven of whose pictures I keep right by the desk where I write today, whose thinking process I enormously admired, and I have to say, it sounds egotistical, but then again I'm a surgeon and I've confessed to you my narcissism anyway, that I was intensely flattered by their taking me seriously. They were people about half a generation older than I, and I realized they were mentors, intellectual mentors, to me, just like my surgical mentors had been. And with those people, it was usually lunch. It would usually be a long lunch, and anything would come up and I would always learn a great deal from it, not just from what I learned from the other person, but because when talking to challenging people like this, things would arise from my mind that I didn't know I was thinking about. Concepts that I had never consciously brought together. And of course, that's a great virtue of hanging out with… people whose minds you admire: you're surprised to find out, as you respond to their thoughts and their questions and their judgements that, my God, you've got thoughts and judgements too. And these people you admire so much are very interested. And that does a great deal for you, because you recognise that you can be like these people, just like the mentorship of surgery. You can be like them.

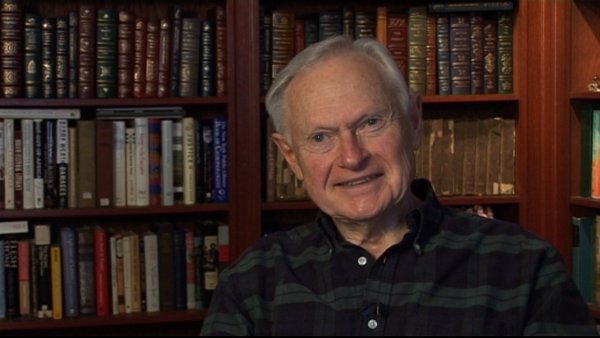

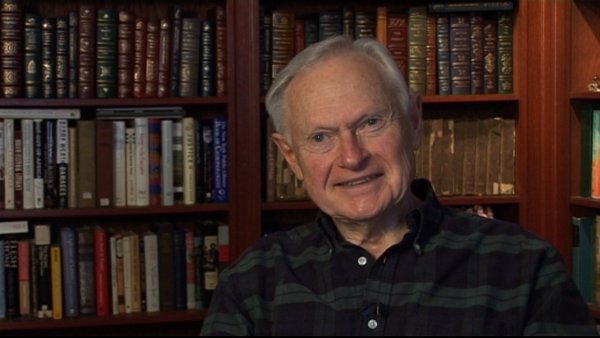

Sherwin Nuland (1930-2014) was an American surgeon and author who taught bioethics, the history of medicine, and medicine at the Yale University School of Medicine. He wrote the book How We Die which made The New York Times bestseller list and won the National Book Award. He also wrote about his own painful coming of age as a son of immigrants in Lost in America: A Journey with My Father. He used to write for The New Yorker, The New York Times, Time, and the New York Review of Books.

Title: The difference between information, knowledge and wisdom

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: Constantinopole, Spain, Leonardo da Vinci

Duration: 4 minutes, 45 seconds

Date story recorded: January 2011

Date story went live: 04 November 2011