NEXT STORY

Properties of human tumor tissue

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Properties of human tumor tissue

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 51. Cell division | 82 | 03:00 | |

| 52. Cryobiology | 62 | 02:53 | |

| 53. Studying the transformation of normal cells into cancerous cells | 81 | 01:51 | |

| 54. HeLa cells | 126 | 02:02 | |

| 55. The WISH cell line | 133 | 01:56 | |

| 56. Testing cell cultures for contamination with mycoplasmas | 82 | 02:30 | |

| 57. Setting cell cultures using human embryonic tissue | 102 | 02:42 | |

| 58. Properties of human tumor tissue | 61 | 02:36 | |

| 59. Testing cell cultures for sensitivity to human viruses | 50 | 03:47 | |

| 60. Discovering a new rhinovirus | 54 | 00:35 |

So because of the reasons that I explained, I wanted to get tissue from human embryos because they presumably lacked interfering viruses and that's what I was looking for in the cancer cells. Well, that was very difficult to do. First of all, you... at that time you didn't have to get permissions, the kinds of permissions that you can today, so it wasn't necessary to get permissions, but it was necessary to arrange things so that you were called on the telephone from a local hospital – notably again the University of Pennsylvania Hospital, which was a huge facility – to be alerted when that tissue becomes available, when an embryo is surgically aborted. The cancer tissue was available almost on a daily basis, so we sent somebody over to the cancer department every day at the end of the day and usually picked up one or two specimens.

But the embryonic tissue was an entirely different story. So in a sense, we had to have people in the paediatric unit pay attention to what we wanted and that was done by convincing the physicians there of why it was important that we get this tissue rather than to incinerate it, which was usually done. And to have cooperation with the nursing staff, etc. And those things were arranged, but as you can well imagine, the telephone would ring saying that embryonic tissue was available at random times, usually five minutes before the end of the working day, which would necessitate calling your family and telling them you won't be home for two more hours because you needed to process the tissue immediately. Of course, that's facetious, but it's usually what happened, Murphy's law at work. So the cultures were set only when... two or three hours after the phone rang which happened sporadically. So what I had done was to initiate culture every time we received an embryo at these random times, set the cultures and did the subcultivation process as they grew out and kept records of the numbers of times that I would do what we call a split or a subcultivation.

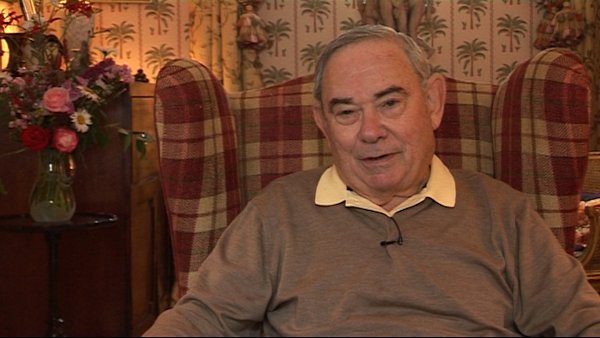

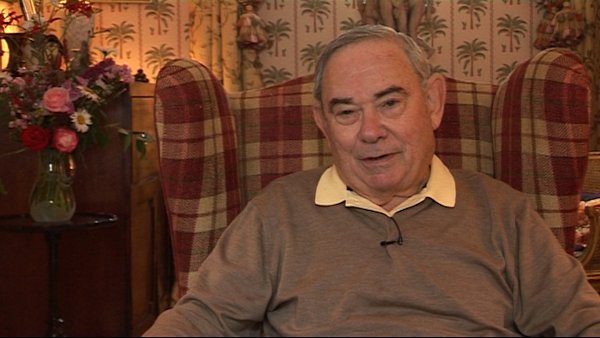

Leonard Hayflick (b. 1928), the recipient of several research prizes and awards, including the 1991 Sandoz Prize for Gerontological Research, is known for his research in cell biology, virus vaccine development, and mycoplasmology. He also has studied the ageing process for more than thirty years. Hayflick is known for discovering that human cells divide for a limited number of times in vitro (refuting the contention by Alexis Carrel that normal body cells are immortal), which is known as the Hayflick limit, as well as developing the first normal human diploid cell strains for studies on human ageing and for research use throughout the world. He also made the first oral polio vaccine produced in a continuously propogated cell strain - work which contributed to significant virus vaccine development.

Title: Setting cell cultures using human embryonic tissue

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: human embryonic tissue, cancer tissue, cell cultures, subcultivation

Duration: 2 minutes, 42 seconds

Date story recorded: July 2011

Date story went live: 08 August 2012