NEXT STORY

Is the voice the same as a character?

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Is the voice the same as a character?

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 61. Sex in the '50s | 481 | 04:41 | |

| 62. Memories of World War II | 410 | 04:55 | |

| 63. The Korean War | 306 | 01:45 | |

| 64. Fear and Indignation | 283 | 00:24 | |

| 65. My father wanted me to be a lawyer | 315 | 03:37 | |

| 66. How writers work | 760 | 01:02 | |

| 67. I read a helluva lot... | 742 | 01:32 | |

| 68. Influences? Saul Bellow and Augie March | 1 | 1275 | 04:56 |

| 69. Writing from my own experience | 512 | 01:44 | |

| 70. Finding a voice - and using what I knew | 532 | 03:32 |

Well, you don't... you don't find a voice by looking for it. You... you try one out. I'll give you an example from my beginnings. The voice that narrates Goodbye, Columbus is not the voice that narrates Letting Go, my next book. The first voice is colloquial and it's not exactly in the vernacular, but close to it. Letting Go is much more, I should say, artificial maybe, and further away from spoken speech. I'm not speaking about the dialogue, I'm speaking about the narrative. Further away from spoken speech. I was writing... I was writing a big novel and I wanted, as it were, a big and impressive voice. I don't think either of those books is successful, by the way, I'm just telling you how I... how I began.

When I got around to my third book, which is called When She Was Good, which takes place in a mid-western town in the 1940s, I tried to find a plain American voice that would not overwhelm the subject, and it's a little spare, and probably lacks colour, you know. But those were my first three shots out and each one I did something else in response to the material. The voice is a response to the material.

And then my fourth time out I wrote Portnoy's Complaint, which was total… the voice is totally unlike the voice in the first three books, but I found my colloquial freedom and I, sort of thought anything goes, anything goes. And... I used a psychoanalytic session as the prop. That is, the book is... the book is said to be told… it's said to be told by a patient speaking to his doctor in a psychoanalytic session. Well one of the rules of psychoanalysis is you say anything and everything, you don't censor yourself. And so this gave me great latitude of a kind I never could have taken without the psychoanalytic session as my prop, but I had… I found my freedom in that book. I wasn't going to use that voice again, I never have, actually. And those would be four instances of a writer, a young writer, finding a voice appropriate to the material and changing each time.

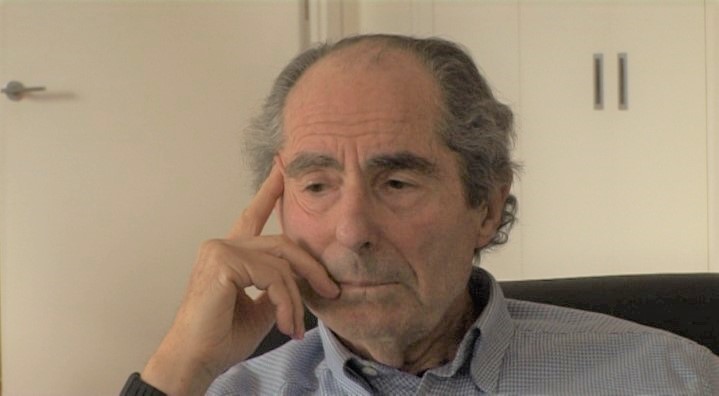

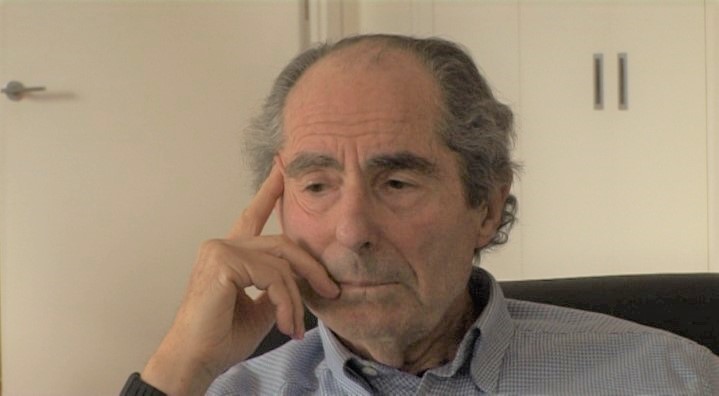

The fame of the American writer Philip Roth (1933-2018) rested on the frank explorations of Jewish-American life he portrayed in his novels. There is a strong autobiographical element in much of what he wrote, alongside social commentary and political satire. Despite often polarising critics with his frequently explicit accounts of his male protagonists' sexual doings, Roth received a great many prestigious literary awards which include a Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1997, and the 4th Man Booker International Prize in 2011.

Title: Finding a voice - and using what I knew

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: Goodbye Columbus, Letting Go, When She Was Good, Portnoy's Complaint

Duration: 3 minutes, 32 seconds

Date story recorded: March 2011

Date story went live: 18 March 2013