NEXT STORY

Dinner with friends was improvisational theatre

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Dinner with friends was improvisational theatre

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 71. Is the voice the same as a character? | 434 | 00:18 | |

| 72. Portnoy's Complaint: using psychoanalysis | 551 | 03:09 | |

| 73. Freedom: unleashing the gush | 352 | 00:59 | |

| 74. Portnoy’s Complaint: freedom to move | 296 | 01:15 | |

| 75. My clown | 315 | 03:21 | |

| 76. Dinner with friends was improvisational theatre | 297 | 01:52 | |

| 77. Portnoy’s Complaint: making my mother cry | 451 | 03:41 | |

| 78. Portnoy’s Complaint: sending my parents on a... | 390 | 01:25 | |

| 79. Portnoy’s Complaint: my mother’s question | 455 | 00:33 | |

| 80. The Portnoy scandal | 395 | 03:49 |

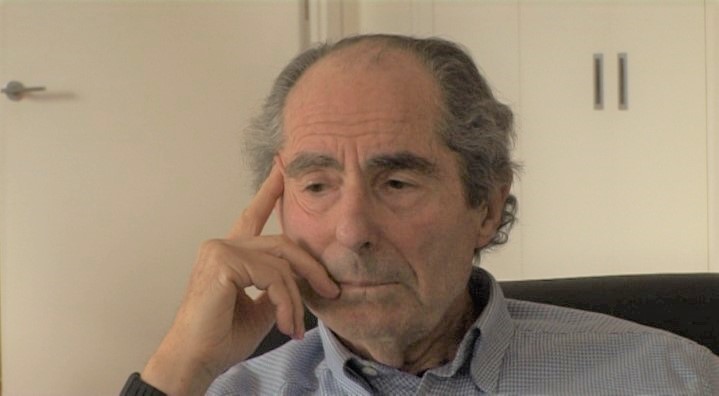

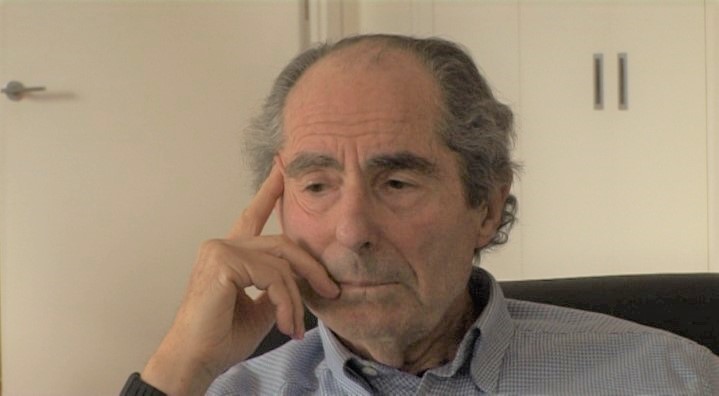

What I was doing in that book was making contact with my non-literary self. That is to say I was making contact with the clown that I knew I could be, with friends in life. The performer, the wild man, verbal wild man. And when I came to New York in the '60s, I fell in with a group of guys who were themselves pretty gifted at this, and we would have… there'd be dinner for… they'd be eight of us at the table say, four men, their wives, their girlfriends, and we would spin out a surreal version of the life we'd known growing up. And what I did in Portnoy's Complaint, was I exploited my talent such as it is, for performance. I'm not a professional performer, I have… I can only perform with friends.

But, those performances that we gave and… were outlandish, were outlandish. And the outlandishness was now coming into my work. Hooray, hooray! Who were the friends? There was Jules Feiffer, the cartoonist, who could be quite funny. There was a friend now deceased, named Al Goldman, who was wonderfully funny. And Bob Brustein who was the… ran the American Repertory Theatre at Harvard. And I guess there were other people who came in and out. But we would do 20 minutes bits, unstoppable, uninhibited, unbuttoned, clever, and then everybody appreciated everybody else's performance. And those were wonderful days and I remember thinking, actually I guess about the time I wrote When She Was Good, how can… how can you get that into your work, you know? There are no laughs in When She Was Good, fewer in Letting Go. So how can you get that in there? And the how was solved for me by the psychoanalytic session. This gave me the permission somehow.

The fame of the American writer Philip Roth (1933-2018) rested on the frank explorations of Jewish-American life he portrayed in his novels. There is a strong autobiographical element in much of what he wrote, alongside social commentary and political satire. Despite often polarising critics with his frequently explicit accounts of his male protagonists' sexual doings, Roth received a great many prestigious literary awards which include a Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1997, and the 4th Man Booker International Prize in 2011.

Title: My clown

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: New York, Portnoy's Complaint, American Repertory Theater, Harvard, When She Was Good, Letting Go, Jules Feiffer, Al Goldman, Bob Brustein

Duration: 3 minutes, 21 seconds

Date story recorded: March 2011

Date story went live: 18 March 2013