NEXT STORY

Being ill-used by Christie's

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Being ill-used by Christie's

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 61. What it means to be an Old Masters drawing expert | 238 | 05:04 | |

| 62. Knowing how to spot a forgery | 259 | 04:06 | |

| 63. Copies, imitations and attribution | 201 | 02:14 | |

| 64. Exposing forgery in art | 289 | 03:05 | |

| 65. Difficult days at Christie's | 253 | 04:45 | |

| 66. A faked van Dyck causes confusion | 256 | 03:29 | |

| 67. Being ill-used by Christie's | 261 | 05:10 | |

| 68. Why I left Christie's | 288 | 05:36 | |

| 69. Moving from the art market to art criticism | 235 | 02:02 | |

| 70. Speaking out in defense of the truth | 274 | 04:10 |

I remember arriving at the office at nine o’clock, which was the time I was supposed to arrive, one morning, and Peter Chance, who was the chairman, was sort of really hopping at the top of the main stairs where my office was. And said, 'Oh, thank God you’ve arrived. We’ve got to go down and see So-and-So, the Bentley’s outside'. So we drive hell-for-leather into Somerset and arrive at the house, and the situation is explained to me that Patrick has been there, has valued the van Dycks at proper van Dyck levels, but the earl or duke or whatever knows perfectly well that these are substitute pictures, that the originals were sold to Duveen in 1902, and these are copies, which Duveen supplied so that nobody would know that the pictures had been sold. And so we were caught out. You know, Patrick was caught out, and…But the man himself was in a rage about it, because he felt that he’d been deceived and perhaps nothing else that Patrick said about anything at the house was of any truth.

And so we arrive. We look at the pictures, they were quite clearly early 20th century canvasses. Early 20th century, we can tell that immediately. And they’re perfectly good replicas, but they have no standing. They’re not even School of van Dyck, they’re centuries later. And so we have the duke and you have the chairman and you have me, the smallest of the three by far, in front of the pictures, and I explain to the chairman that these are really very expert copies and I knew Duveen’s copyist was a man called Pierre Colette [sic] and Colette used to tell all sorts of stories about the stuff that he had faked, and that they were the best of their kind and it had been really perfectly reasonable of Patrick, not knowing the background, seeing them hanging on the wall in normal circumstances and so on, to mistake them for the real thing, which was what Colette intended when he faked them. So you really can’t blame Patrick.

The chairman then turned to the duke, who’d heard all this, and repeated, because there’s a kind of protocol, where I, the minion of absolutely no importance, but the one who knows, cannot speak to the grandee. It has to go through the chairman. And so we have this tripartite conversation. Duke talks to the chairman, chairman talks to me, I talk to chairman, chairman talks to duke. Never the duke and I talking to each other. And that sums up the sort of relic of the class system that obtained in the art world in the early '60s. And it really was… it was ludicrous enough to be bearable.

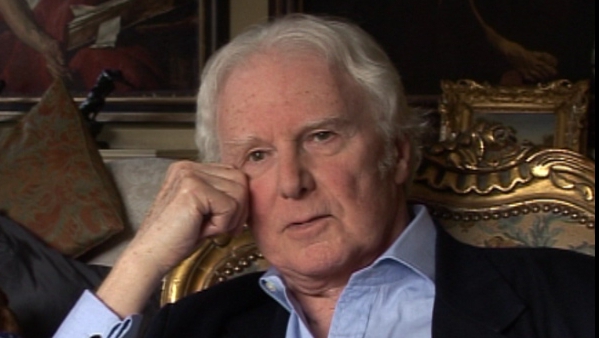

Born in England, Brian Sewell (1931-2015) was considered to be one of Britain’s most prominent and outspoken art critics. He was educated at the Courtauld Institute of Art and subsequently became an art critic for the London Evening Standard; he received numerous awards for his work in journalism. Sewell also presented several television documentaries, including an arts travelogue called The Naked Pilgrim in 2003. He talked candidly about the prejudice he endured because of his sexuality.

Title: A faked van Dyck causes confusion

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: Christie's, School of van Dyck, Anthony van Dyck, Patrick Lindsay, Peter Chance, Joseph Duveen

Duration: 3 minutes, 29 seconds

Date story recorded: April 2013

Date story went live: 04 July 2013