NEXT STORY

In defence of a free society

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

In defence of a free society

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 91. Issuing of the fatwa against The Satanic Verses | 15 | 03:32 | |

| 92. How misinformation fuelled resentment against The Satanic... | 17 | 03:50 | |

| 93. Consternation at Penguin Books | 15 | 04:23 | |

| 94. Fear of reprisals | 13 | 02:05 | |

| 95. Our freedoms at stake | 13 | 05:00 | |

| 96. The reality of living under a fatwa | 20 | 03:31 | |

| 97. Persecuted and victimised for defending our freedoms | 15 | 06:44 | |

| 98. Postponing publication of The Satanic Verses in... | 14 | 06:13 | |

| 99. In defence of a free society | 30 | 02:47 |

There was, of course, much, much more, because the battle ensued over the paperback. I took the view that Salman, wonderful writer that he was, he had his reasons to want the paperback out. I think he thought that the issue of this book would be ended by the publication of a great many paperbacks of The Satanic Verses all over the world.

He may or may not have been right. We don't know. But I did know that I had hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of people all over the world who... for whom I had some responsibility, and who were threatened, and I thought that having won - if you could ever use that word - having won the battle to keep this book alive, that was enough contribution to make right now, or right at that time, when the anger about it was still there.

And so, I said, we'll decide when we publish the paperback book. We will publish the paperback, but we'll decide when it's safe to do so. I have a great many people to worry about, who look to me for some kind of comfort and security, and if I think it's unsafe, or I'm advised by the Home Office or the Metropolitan Police or by anybody else that it's unsafe, I will now, having fought a battle not paying attention to our safety, I will now not stick a poker in the eye of the people who are angry about this book, and I'll let things calm down.

We had at that time book stores, and one of them was bombed. Happily… I think, actually, more than one was bombed, but one was bombed on the day when our board met, and in a three- or four-hour meeting, decided to proceed with the paperback, because we thought it was safe. And on my way to Heathrow - we had the car radio on - we heard that one of the bookshops had been bombed, no one dead but bombed, and I turned around in the car and I said, I'm not flying to the US today, I'm going back to our office, and I'm going to further postpone the paperback. Because Salman may believe that it's the solution of all time to put the paperback out, but I have to worry that it may be something that will inflame [those who are already inflamed]. Even… not only is the book not withdrawn, but even more copies are printed, and even cheaper! So, Salman can't know the outcome of that. There's a risk doing things either way. And as I felt that Penguin had already performed by refusing to let this book die - it was available in libraries all over the world, and in foreign languages and so on - the book had been preserved.

And, for me, that was a very cardinal aspect of the whole thing, to present myself as a publisher who supported a right to write, read, purvey, and so on. I saw myself that. Did I not think about Salman's wellbeing? Well, of course I did. But you have to act in a timeframe, and I said we'll publish the [paperback] later.

We… through this entire period, nobody at Penguin gave statements to the press. We didn't permit pictures of anyone at Penguin to appear in the newspaper. Salman took a different view, for whatever reason. His picture was everywhere. He knew it. Want to say he liked it or didn't like it. But he thought it was important to show the flag, show his flag, if you like.

But, of course, he was guarded. We were not. We had to go home. Each one of us individually, from the office to the tube, or walking, and in many countries. We had literally no protection. The premises that we worked in were protected, but individually, we didn't. Whereas, Salman had individual protection.

I'm not saying anything negative about Salman whatsoever. I can appreciate his argument. But I had different concerns: the concerns of the people who worked at Penguin.

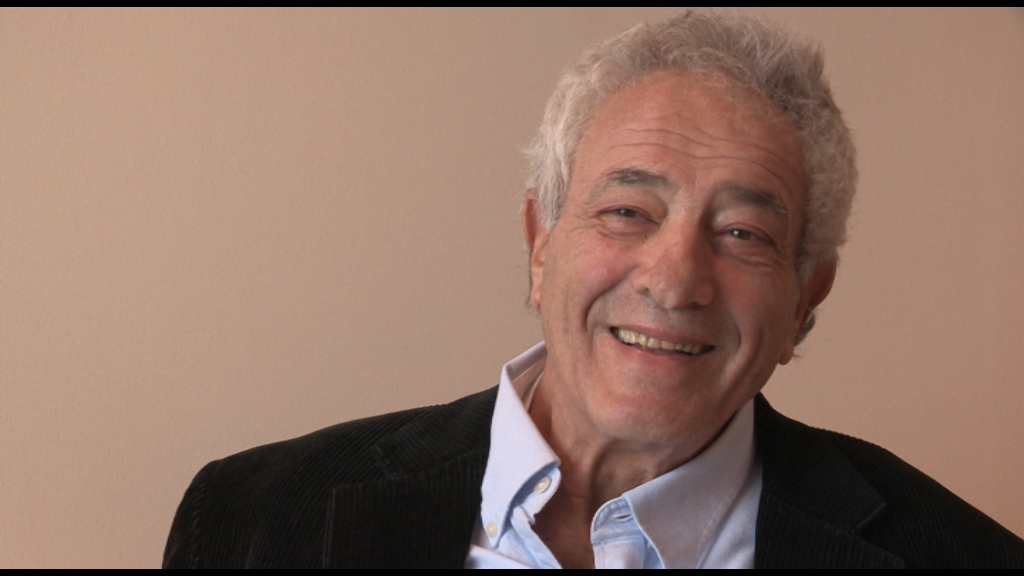

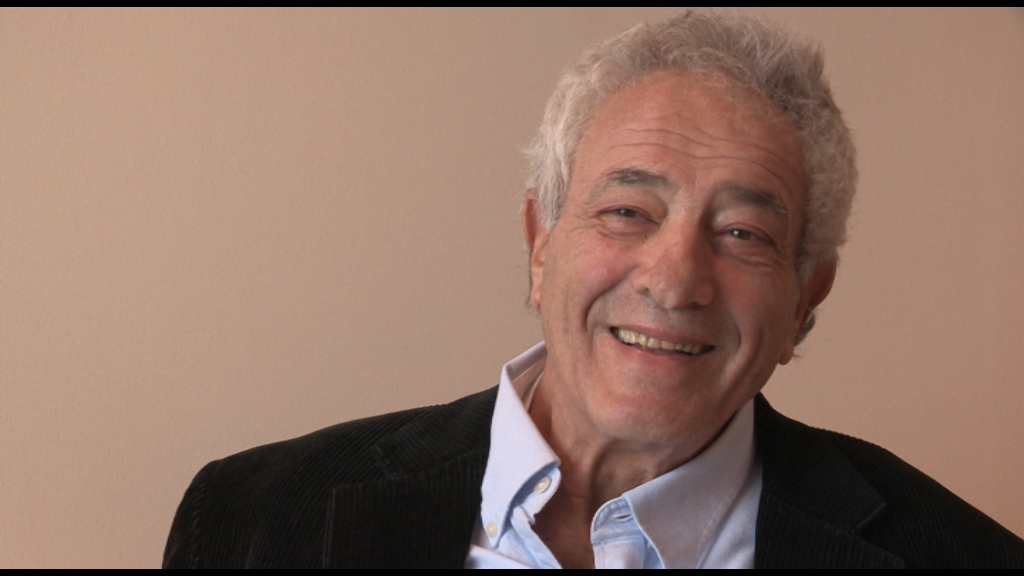

Peter Mayer (1936-2018) was an American independent publisher who was president of The Overlook Press/Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc, a New York-based publishing company he founded with his father in 1971. At the time of Overlook's founding, Mayer was head of Avon Books, a large New York-based paperback publisher. There, he successfully launched the trade paperback as a viable alternative to mass market and hardcover formats. From 1978 to 1996 he was CEO of Penguin Books, where he introduced a flexible style in editorial, marketing, and production. More recently, Mayer had financially revived both Ardis, a publisher of Russian literature in English, and Duckworth, an independent publishing house in the UK.

Title: Postponing publication of "The Satanic Verses" in paperback

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: Penguin Books, Salman Rushdie

Duration: 6 minutes, 13 seconds

Date story recorded: September 2014-January 2015

Date story went live: 12 November 2015