NEXT STORY

Working with Alden Spencer

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Working with Alden Spencer

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21. I decide to learn how memory works | 148 | 04:04 | |

| 22. Working with Alden Spencer | 98 | 02:38 | |

| 23. Thrilling discoveries about intracellular activity | 99 | 02:35 | |

| 24. Discovering Aplysia | 205 | 02:16 | |

| 25. I’m a Harvard snob! | 144 | 02:56 | |

| 26. Goldfish brains | 103 | 01:12 | |

| 27. I begin to work on Aplysia | 119 | 02:36 | |

| 28. Using Aplysia to study the neuroscience of behavior | 176 | 02:43 | |

| 29. Investigating the mechanisms of learning and memory | 137 | 04:43 | |

| 30. Working with Ladislav Tauc | 91 | 03:41 |

So when a year later I came to the NIH [National Institutes of Health], I had this idea in mind. And Wade Marshall, the guy who recruited me, was a very interesting guy. He had been in the ‘30s an absolute giant. He probably would have gotten the Nobel Prize if he had continued working. He was a graduate student with Ralph Gerard and recorded from the surface of the cortex with evoked response electrode, with gross electrodes, and he saw that if you stimulated the surface of the body, you got in a certain area of the brain, evoked responses. And there seemed to be a bit of a map, topographical representation. So he thought he would go to Hopkins where Phillip Bard was studying somatic sensation, and collaborate with him. And they published a famous series of papers – Marshall, Woolsey and Bard – in which they mapped the body representation on the brain. Classic studies. It then went on with somebody specializing in the ear, to do the representation of the cochlea onto the brain, and then the retina, with Talbot. Fabulous papers.

Phillip Bard was asked to give the Harvey Lecture [at the] Harvey Society in New York, and those papers were published and he published under his own name, the data that he collected together with other people, including data from Marshall. So Marshall’s papers, some of Marshall’s figures, first appeared in Bard’s paper, the Harvey Lecture. Wade went off his rocker and threatened to kill Bard. He really had a psychotic episode. Bard was a big man, took the gun away from him, helped him get hospitalized, and he was hospitalized for several years. When he got out, he was recruited first to the naval medical center, and then to the NIH where Seymour Kety, who was head of a large laboratory, made him head of a sub-branch, the Laboratory of Neurophysiology, both for NINDS and for NIMH both for neurology and for mental health. And there he ran a moderate-sized laboratory, actually one set-up. And he was interested in spreading cortical depression, sort of a migraine-like phenomenon that propagates over the cerebral cortex. And I helped him with that, and Jack Brindley, who joined the lab at the same time, also helped him with that and we collaborated together. We actually published a paper together on that.

And then he let Jack and me do whatever we wanted to. So I thought, you know, what’s the problem I should work on? And I thought the key problem in psychoanalysis is memory. We are who we are because of what we learn and we remember. And psychoanalysis is an attempt to create a comfortable environment so you can relive traumatic memories from early life in a protective environment. So I thought I would like to learn how memory works and like to do it on a cellular level.

Brenda Milner had just collaborated with Scoville who had removed the hippocampus on both sides, and together they had showed [that the] hippocampus was absolutely essential for memory storage. And I thought I would apply single cell techniques to the hippocampus. Jack Brindley had zero interest in that. So we agreed five days a week we’d split the lab two-and-a-half days for him, two-and-a-half days for me. I would help him. He was interested in potassium fluxes. He had been drafted while he was a graduate student at Hopkins, and his thesis was on potassium fluxes, he wanted to continue that, and he would help me with intracellular recordings.

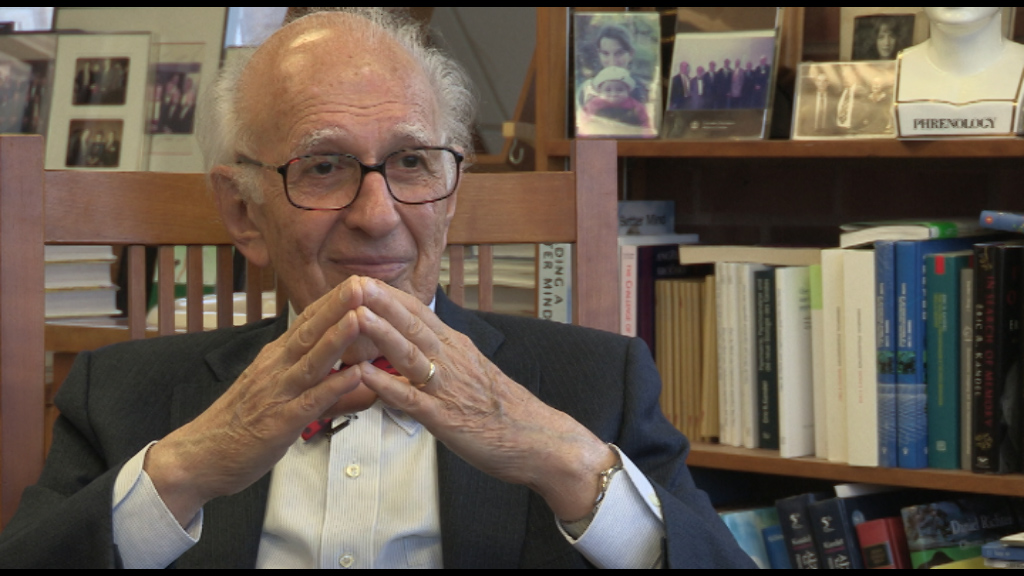

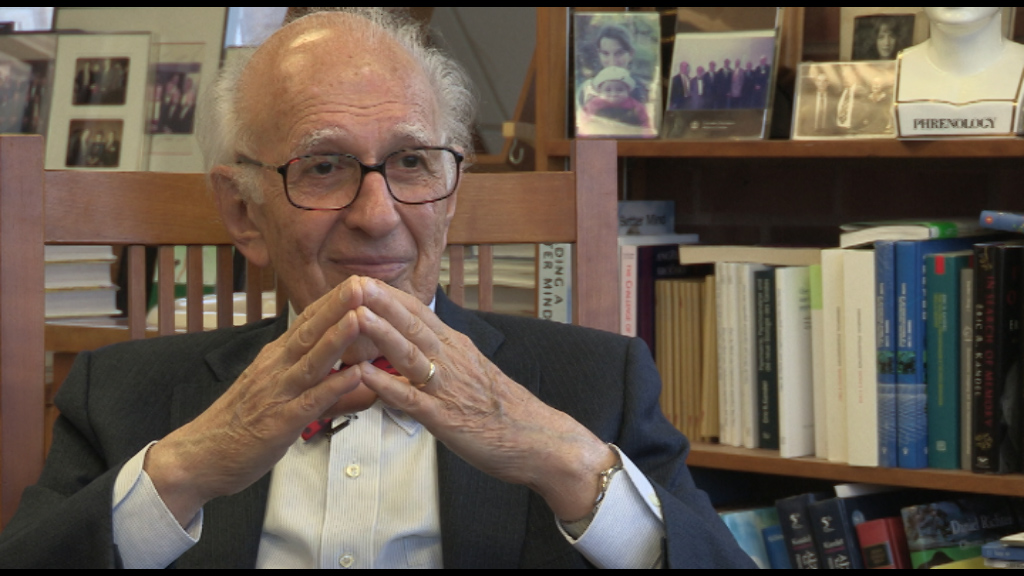

Eric Kandel (b. 1929) is an American neuropsychiatrist. He was a recipient of the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his research on the physiological basis of memory storage in neurons. He shared the prize with Arvid Carlsson and Paul Greengard. Kandel, who had studied psychoanalysis, wanted to understand how memory works. His mentor, Harry Grundfest, said, 'If you want to understand the brain you're going to have to take a reductionist approach, one cell at a time.' Kandel then studied the neural system of the sea slug Aplysia californica, which has large nerve cells amenable to experimental manipulation and is a member of the simplest group of animals known to be capable of learning. Kandel is a professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University. He is also Senior Investigator in the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. He was the founding director of the Center for Neurobiology and Behavior, which is now the Department of Neuroscience at Columbia University. Kandel's popularized account chronicling his life and research, 'In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind', was awarded the 2006 Los Angeles Times Book Award for Science and Technology.

Title: I decide to learn how memory works

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: National Institutes of Health, NIH, Harvey Society, Harry Grundfest, Wade Marshall, Phillip Bard, Clinton Woolsey, Seymour Kety, Brenda Milner, Jack Brindley

Duration: 4 minutes, 4 seconds

Date story recorded: June 2015

Date story went live: 04 May 2016