NEXT STORY

Testing the effects of decompression

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Testing the effects of decompression

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 31. Demonstrating chemotaxis in development | 31 | 02:20 | |

| 32. Wallowing in the developmental aspects of slime mold | 37 | 02:48 | |

| 33. I’m a 19th century biologist | 40 | 01:35 | |

| 34. Learning about high altitude physiology | 28 | 02:55 | |

| 35. Testing the effects of decompression | 24 | 01:56 | |

| 36. Conducting experiments while still in the army | 23 | 02:23 | |

| 37. Giving slime molds a name | 28 | 01:30 | |

| 38. Learning about the facts of life | 32 | 01:57 | |

| 39. Life was fun in Locust Valley | 36 | 04:56 | |

| 40. A typical adolescence | 49 | 00:39 |

Well, that was really weird because I was asked through my father who knows everybody - he was a friend of Charlie Thomas, who was the head at that time of Monsanto, and a very sort of charismatic figure. He was a wonderful man, actually. That was before all of the miserable things that they found doing. And he invited me to give a talk, and I suspect that it was arranged through my father who said, I've got a son, and he does this, that and the other thing. So I gave a talk at Monsanto. And after the talk, there's this colonel, all done up in his fancy colonel clothes came up to me and said, 'What's your draft status?' I said, 'Well, it's pretty grim. It won't be long now'. And he said, 'Well, would you like to work in a laboratory?' And I said, 'Of course'. And he said, 'Well, I'll tell you exactly what to do, and how to get to my lab, which is in Dayton, Ohio. It's the Aeromedical Lab'. And so I spent the war there. And it was wonderful in some ways because I learned an incredible amount of high altitude physiology, not that that helped me with slime molds but it helped me in teaching a lot, and so I could talk about something else besides slime molds. And he arranged so I would come there. And I remember this very clearly because I thought I should call and say, 'I'm here', but there was no opportunity. And so I was given… one of the jobs I was given by the sergeant was to mop out the colonel's office. And I remember this awful feeling: I can't just greet him with a mop in my hand saying, 'I'm a genius with a mop'. And so I hid the mop behind the door when he wasn't there, so I was there with a mop [unclear] without embarrassment.

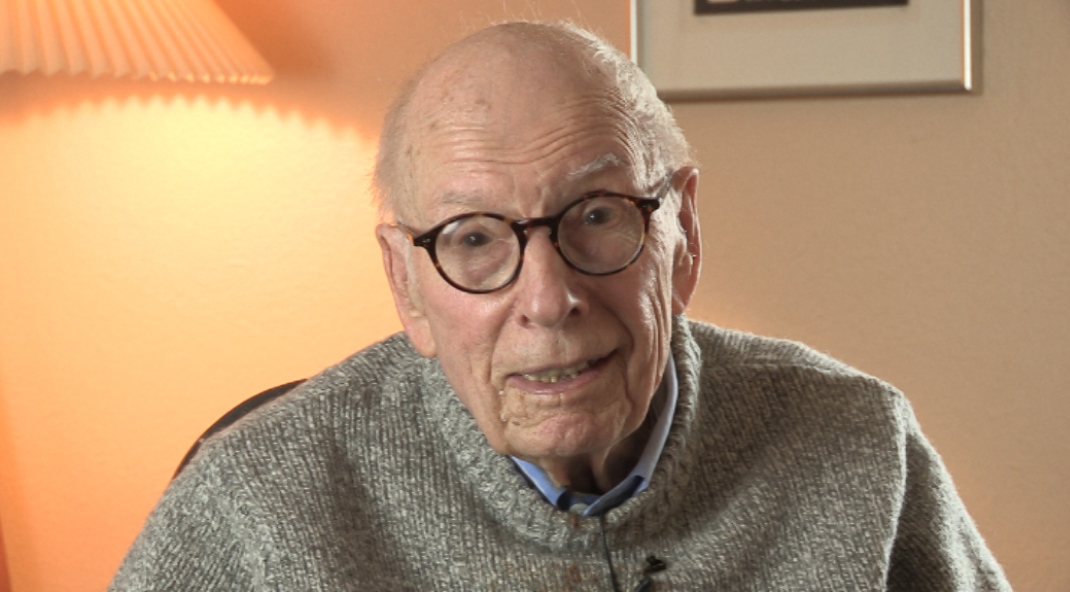

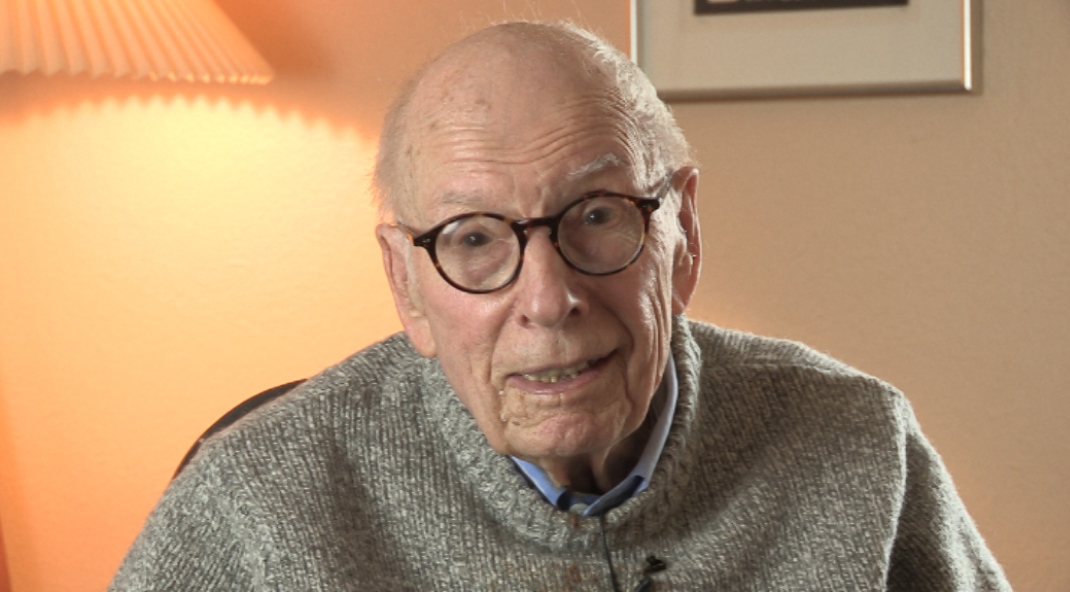

John Tyler Bonner (born in 1920) is an emeritus professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Princeton University. He is a pioneer in the use of cellular slime molds to understand evolution and development and is one of the world's leading experts on cellular slime molds. He says that his prime interests are in evolution and development and that he uses the cellular slime molds as a tool to seek an understanding of those twin disciplines. He has written several books on developmental biology and evolution, many scientific papers, and has produced a number of works in biology. He has led the way in making Dictyostelium discoideum a model organism central to examining some of the major questions in experimental biology.

Title: Learning about high altitude physiology

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: Monsanto

Duration: 2 minutes, 55 seconds

Date story recorded: February 2016

Date story went live: 14 September 2016