NEXT STORY

The effect of moving to Sussex on my theoretical work

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The effect of moving to Sussex on my theoretical work

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 31. Work on ageing | 847 | 03:36 | |

| 32. Changing patterns in fruit flies through genetic manipulation | 732 | 02:40 | |

| 33. Haldane's reaction to the Lysenko affair | 2 | 1180 | 04:29 |

| 34. The story of Haldane's last words | 2 | 1559 | 02:16 |

| 35. The move to Sussex University | 793 | 01:19 | |

| 36. Bill Hamilton | 1366 | 04:26 | |

| 37. The first idea of population regulation by group selection | 1 | 1118 | 05:12 |

| 38. Hamilton and Haldane's ideas of 'inclusive fitness' | 1054 | 01:52 | |

| 39. Hamilton: political and ideological commitment | 1037 | 02:42 | |

| 40. WD Hamilton: inclusive fitness | 2 | 1202 | 04:21 |

There's a striking thing, at least about the '64 paper, is that he defines something which he calls inclusive fitness, which is an absolute swine to calculate, if you've ever tried it, in practice. It's awfully easy to get it wrong. But it's a measure that you can put on an individual organism, such that if you take group of - a population of organisms and ascribe to each one its inclusive fitness, or each kind, its inclusive fitness, it will correctly predict what will happen to the population. And with certain restrictions that he's very clear about and makes very explicit in his paper, he succeeds in this task. He does find a measure that you can ascribe to an individual which will then predict. But I think, certainly you from your writings, and others, have found it a very hard way to think about the problem. It's much easier to think about if I was a gene, what would I do? And I have to say, when I think about what I think of as a Hamilton-type problem, I do say to myself, if I was a gene, what would I do?

[Q] Oddly enough, that's what he did, in 1963, in a short paper in The American Naturalist which predates The Journal of Theoretical Biology papers you're talking about.

Yes, just so.

[Q] He says just that.

So it's very strange. I don't understand why he, in a sense, drew back from the '63 model, and presents this very, very much more difficult model. I think his ideas would have been accepted much quicker, perhaps, it's hard to say. You must remember that prior to '63 and Hamilton's paper, all population genetics models had been based on the notion of ascribing a fitness to an individual or to a class of individuals. And indeed, one was taught that you must not ascribe fitness's to genes. Even Haldane, I can remember effectively, saying that in his lectures, one must ascribe fitness to genotypes but not to genes. So in his '63 paper, when he talked about the gene-centred way of looking at it, he was departing from an orthodoxy. But what I'm curious about is; did he draw back from the gene centred view because he thought his views would be more readily accepted if he cast them in an individual selection individual organism kind of model, or did he - I have a feeling, reading the paper, that it was a deeper reason than that. That he had been - I think he was actually a student of RA Fisher's, he certainly was much influenced by RA Fisher. He wanted to save Fisher's Fundamental Theorem of Natural Selection. Now, I regard Fisher's Fundamental Theorem of Natural Selection as either false or trivial, depending upon how you interpret it. But for anybody who's been a student of Fisher's, it's the holy grail. I mean it's very interesting how we divide on this one, I wouldn't care throwing the theorem away and forgetting it, I don't think it's fundamental at all. But I think Bill does or certainly did think it was important and fundamental and wished to save it, and the only way you could save it would be to find some new way of defining fitness so that it remained true. So I think he had a more important reason than just wanting his views to be readily acceptable... But it really would interesting to sit round a table with him and sort this one out, because there's this other thread which goes back to George Williams in 1966 and to your Selfish Gene book, which really has made the gene-centred view, I think, of seeing the world, the way we all do it now. I mean, is that the way you see it? I mean, that really is the way we see the world. And it's now led on to a whole world of intragenomic conflict, really a world which is looking at genes as the units of evolution and selection. And it's really very odd that he didn't immediately follow up the '63 formulation and, in a sense, stuck with what, to me, is a more old fashioned formulation. It's a very interesting problem.

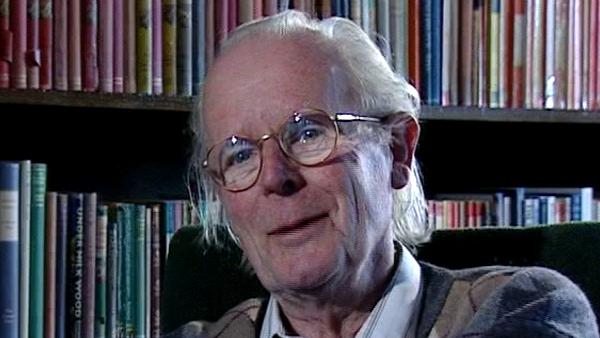

The late British biologist John Maynard Smith (1920-2004) is famous for applying game theory to the study of natural selection. At Eton College, inspired by the work of old Etonian JBS Haldane, Maynard Smith developed an interest in Darwinian evolutionary theory and mathematics. Then he entered University College London (UCL) to study fruit fly genetics under Haldane. In 1973 Maynard Smith formalised a central concept in game theory called the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS). His ideas, presented in books such as 'Evolution and the Theory of Games', were enormously influential and led to a more rigorous scientific analysis and understanding of interactions between living things.

Title: WD Hamilton: inclusive fitness

Listeners: Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins was educated at Oxford University and has taught zoology at the universities of California and Oxford. He is a fellow of New College, Oxford and the Charles Simonyi Professor of the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University. Dawkins is one of the leading thinkers in modern evolutionary biology. He is also one of the best read and most popular writers on the subject: his books about evolution and science include "The Selfish Gene", "The Extended Phenotype", "The Blind Watchmaker", "River Out of Eden", "Climbing Mount Improbable", and most recently, "Unweaving the Rainbow".

Tags: inclusive fitness, 1964, The Genetical Evolution of Social Behaviour, 1963, The American Naturalist, The Journal of Theoretical Biology, The Selfish Gene, Robert Fisher, WD Hamilton, George Williams, Richard Dawkins

Duration: 4 minutes, 22 seconds

Date story recorded: April 1997

Date story went live: 24 January 2008

Wednesday, 10 January 2018 02:23 AM

I would love to know why John Maynard Smith regards R.A. FIsher's Fundamental of Natural Selection as...

More...