NEXT STORY

Larry Gilbert and Nick Davis

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Larry Gilbert and Nick Davis

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41. The effect of moving to Sussex on my theoretical work | 1 | 794 | 02:35 |

| 42. My first encounters with game theory, courtesy of George Price | 1620 | 03:10 | |

| 43. Developing the Evolutionary Stable Strategy theory | 1381 | 03:29 | |

| 44. Publishing a paper with George Price | 1272 | 02:25 | |

| 45. George Price's theorem and how scientists think | 1 | 2052 | 04:02 |

| 46. Game theory: The war of attrition game | 1450 | 04:16 | |

| 47. The War of Attrition game in Papilio zelicaon | 1035 | 02:34 | |

| 48. Geoffrey Parker's dung flies | 866 | 02:08 | |

| 49. Larry Gilbert and Nick Davis | 845 | 01:48 | |

| 50. The point of evolutionary game theory | 1527 | 03:49 |

Geoff had done his PhD on these dung flies which - basically the story is, it's like the hilltops essentially - the female dung flies who want to mate go to cow-pats, and the males who want to catch females, hang around cow-pats waiting for females to turn up. And the problem was essentially to do with, if you're a male, how long should you stay at the cow-pat, and how long - perhaps the cow-pat's getting a bit stale, the females aren't turning up too quickly, should you go to another cow-pat and so on. And he spent hours with his nose within inches of cow-pats, recording how long males hung around and so on. And had worked out a strategy that the flies were actually adopting. It wasn't quite my war of attrition game but it jolly nearly was, actually. And when I read this thing, I got in touch with Geoff, and we started talking about games, because it was clear to me that he'd, in effect, applied the game theory arguments to his dung flies. And we revisited the asymmetric contest thing because we were interested in all sorts of questions to do with - well, one of the questions we were interested in, I mean, Geoff was a good Socialist in those days, you see; I don't know whether he still is, and he was worried about this bourgeois thing, because, after all, owner stays, intruder leaves, is an ESS, but so is intruder stays, owner leaves, and why shouldn't we do that? Much more sharing and so on. The trouble with it, of course, it leads to an infinite regress, because as soon as you own, then you've got to leave when somebody else turns up and nobody ever settles down to getting anything. But it was these kind of issues that Geoff and I got interested in when we met. And we wrote a paper in JTB about Asymmetrical Contests. And he was also interested in this problem that I mentioned earlier in relation to sexual selection, the difference between whether you fail to do something because you can't or you fail to do something because you don't want to, and we tried to formalise that and so on.

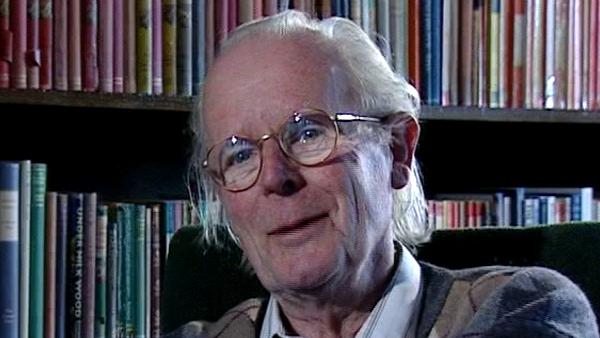

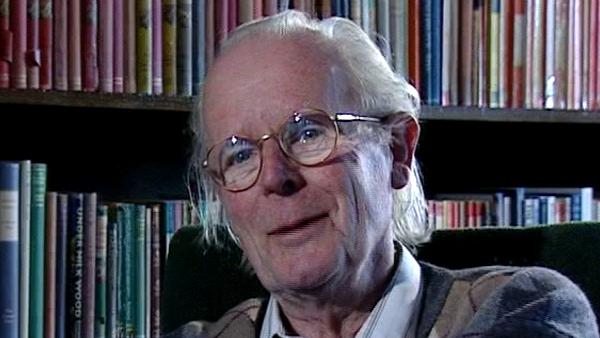

The late British biologist John Maynard Smith (1920-2004) is famous for applying game theory to the study of natural selection. At Eton College, inspired by the work of old Etonian JBS Haldane, Maynard Smith developed an interest in Darwinian evolutionary theory and mathematics. Then he entered University College London (UCL) to study fruit fly genetics under Haldane. In 1973 Maynard Smith formalised a central concept in game theory called the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS). His ideas, presented in books such as 'Evolution and the Theory of Games', were enormously influential and led to a more rigorous scientific analysis and understanding of interactions between living things.

Title: Geoffrey Parker's dung flies

Listeners: Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins was educated at Oxford University and has taught zoology at the universities of California and Oxford. He is a fellow of New College, Oxford and the Charles Simonyi Professor of the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University. Dawkins is one of the leading thinkers in modern evolutionary biology. He is also one of the best read and most popular writers on the subject: his books about evolution and science include "The Selfish Gene", "The Extended Phenotype", "The Blind Watchmaker", "River Out of Eden", "Climbing Mount Improbable", and most recently, "Unweaving the Rainbow".

Tags: Game Theory, Evolutionary Stable Strategy, Journal of Theoretical Biology, The logic of asymmetric contests, Geoffrey A Parker

Duration: 2 minutes, 9 seconds

Date story recorded: April 1997

Date story went live: 24 January 2008