NEXT STORY

How bacteria transfer genetic material

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

How bacteria transfer genetic material

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 71. Penicillin | 606 | 02:05 | |

| 72. How bacteria transfer genetic material | 582 | 01:03 | |

| 73. The process of transfer in bacteria | 485 | 03:39 | |

| 74. Operons: JG Roth and JR Lawrence. Jacob and Monod | 572 | 04:23 | |

| 75. Adaptation at the organism level | 556 | 01:00 | |

| 76. James Watson and Francis Crick transformed biology | 1339 | 00:42 | |

| 77. Viviparity may be a big evolutionary mistake! | 1 | 555 | 02:49 |

| 78. Are mammals stuck with sex? | 586 | 03:54 | |

| 79. Dolly the sheep, and would you clone yourself? | 719 | 01:58 | |

| 80. Sheila Maynard Smith | 1 | 805 | 03:34 |

Penicillin kills bacteria by binding to some enzymes called, rather curiously, penicillin-binding proteins. When I first heard of them I thought their function was to bind penicillin, it's nothing of the sort. Their function is to make the cell wall, and the penicillin comes in and binds to them and prevents them making the cell wall and the bacterium dies. Now, we find that some of these commensal bacteria are naturally resistant to penicillin. That means to say, if you take an isolate out of the freezer, which was put there before the clinical use of penicillin, back in the 1940s or something, they're already resistant to a drug they've never met, and I think never could have met it. I mean, there's plenty of penicillin being produced in the soil by soil... fungi, and so if I found a soil bacterium which was resistant to penicillin, it would make sense as having happened by natural selection. But it's very hard to explain why something in our throats which could never have met penicillin, I think, should have this resistance. I think it's just a matter of chance as to whether the penicillin could or couldn't bind in an appropriate way to the enzyme. On the other hand, once a piece of that gene was transferred into a... the bacteria in our throats, and penicillin was being used, the selection favouring it would be enormously powerful, of course.

[Q] But was that gene doing anything in the original ones who just were spontaneously resistant?

It was certainly making cell walls, but I think the fact that it was spontaneously resistant was just an accident, that's my guess. It's hard to be sure. And the alternative is that... that it evolved by natural selection in soil bacteria, and then, by some accidental process, it's got transferred into the throat.

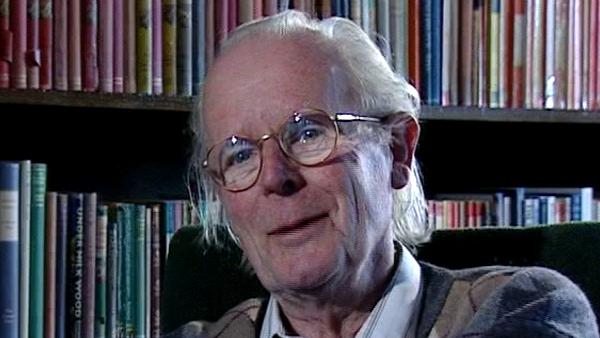

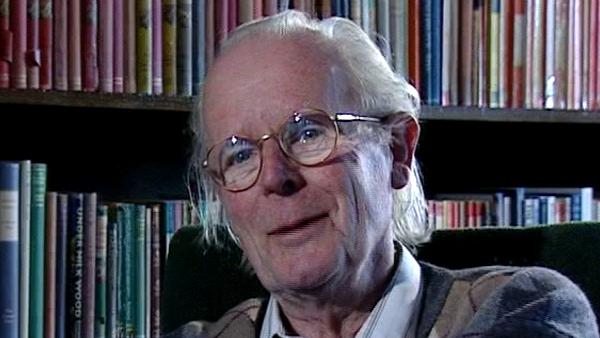

The late British biologist John Maynard Smith (1920-2004) is famous for applying game theory to the study of natural selection. At Eton College, inspired by the work of old Etonian JBS Haldane, Maynard Smith developed an interest in Darwinian evolutionary theory and mathematics. Then he entered University College London (UCL) to study fruit fly genetics under Haldane. In 1973 Maynard Smith formalised a central concept in game theory called the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS). His ideas, presented in books such as 'Evolution and the Theory of Games', were enormously influential and led to a more rigorous scientific analysis and understanding of interactions between living things.

Title: Penicillin

Listeners: Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins was educated at Oxford University and has taught zoology at the universities of California and Oxford. He is a fellow of New College, Oxford and the Charles Simonyi Professor of the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University. Dawkins is one of the leading thinkers in modern evolutionary biology. He is also one of the best read and most popular writers on the subject: his books about evolution and science include "The Selfish Gene", "The Extended Phenotype", "The Blind Watchmaker", "River Out of Eden", "Climbing Mount Improbable", and most recently, "Unweaving the Rainbow".

Tags: penicillin, bacteria, cell wall

Duration: 2 minutes, 5 seconds

Date story recorded: April 1997

Date story went live: 24 January 2008