NEXT STORY

Writing up papers

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Writing up papers

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 51. Klaus Fuchs. The US Reactor Safeguard Committee | 706 | 04:13 | |

| 52. The reactor project | 444 | 03:08 | |

| 53. That Xenon and Iodine Business | 485 | 04:40 | |

| 54. More detailed account of the Hanford problems. Fermi's agreement | 407 | 03:29 | |

| 55. Locating the Du Pont pile. Washingon and the Cascade Mountains | 373 | 02:37 | |

| 56. MetLab, Chicago 1942. Wheeler and Wigner. Reactor coolants | 398 | 04:22 | |

| 57. Writing up papers | 472 | 01:09 | |

| 58. 'Boiled down' explanation of 'action at a distance' concept | 660 | 00:47 | |

| 59. The conception of an electron moving backward in time | 1048 | 02:15 | |

| 60. Polyelectrons | 421 | 01:58 |

At Chicago, in the beginning, in early 1942, it was a bit of a 'catch-as-catch-can' operation. To be sure, there was a natural division for the organization between chemistry and physics, between chemistry of separating plutonium and physics of making a reactor go that would make plutonium. But in the physics, there was a division between figuring the proper dimensions to get the most effective and the most efficient reactor, on the one hand, and talking about how to get the thing going on an engineering level with lots of heat pouring out of it and being taken away by cooling devices. I can remember that so many of us felt that any fluid that could be used in cooling would take away from the reactivity, which we didn't know would be enough, and therefore we ought to insist on absolute minimum neutron absorption by the coolant. Well the only thing we knew that had that property was helium gas. Well, Eugene Wigner had enough vision to think that we could get the reactivity we needed to use as the cooling medium, water, which absorbed a significant number of neutrons, so-- as helium gas didn't appeal to him so much - but in the end that was the right route to follow. But I didn't have his faith in getting the reactivity, and so I pushed for the helium. And I can remember thinking of one bug, one problem that people had raised; won't the helium, as it goes through, erode the graphite and cause the system to fail? So I got an experiment set up in the lab and we ran helium through bricks of graphite and measured a negligible amount of erosion of the graphite blocks. But that was my first and only significant venture into engineering, pile engineering. And, of course, when I was with the Du Pont people, I was very much the engineering side, and the control devices, all the different ways that you could do -- Cadmium rod, pull it out, or put it in; or, if you got into real trouble, had a lot of holes in the pile, then pour boron BBs down the hole. Much harder to get out than to pull a rod out. It would be hard for me at this late date, and state of my memory, to remember exactly what the division of duties was for some time. But I know Eugene and I -- Eugene Wigner and I -- were occupied with the different problems.

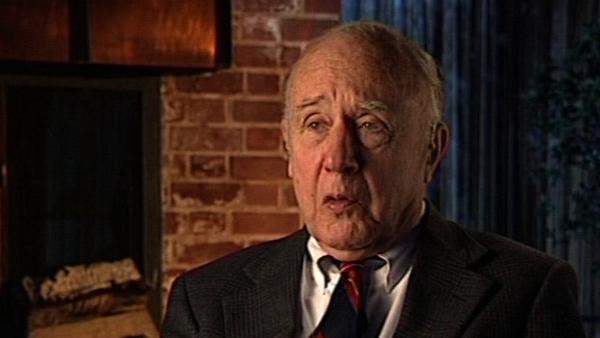

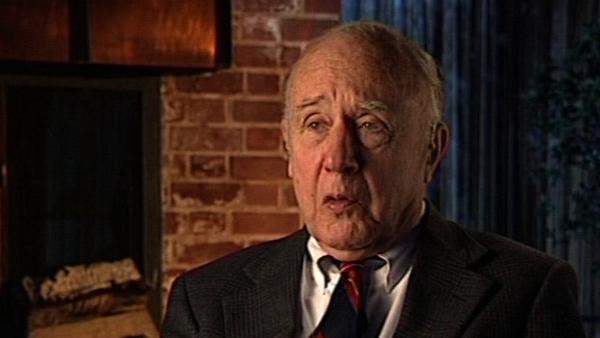

John Wheeler, one of the world's most influential physicists, is best known for coining the term 'black holes', for his seminal contributions to the theories of quantum gravity and nuclear fission, as well as for his mind-stretching theories and writings on time, space and gravity.

Title: MetLab, Chicago 1942. Wheeler and Wigner. Reactor coolants

Listeners: Ken Ford

Ken Ford took his Ph.D. at Princeton in 1953 and worked with Wheeler on a number of research projects, including research for the Hydrogen bomb. He was Professor of Physics at the University of California and Director of the American Institute of Physicists. He collaborated with John Wheeler in the writing of Wheeler's autobiography, 'Geons, Black Holes and Quantum Foam: A Life in Physics' (1998).

Duration: 4 minutes, 23 seconds

Date story recorded: December 1996

Date story went live: 24 January 2008