NEXT STORY

Difficult days at Christie's

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Difficult days at Christie's

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 61. What it means to be an Old Masters drawing expert | 238 | 05:04 | |

| 62. Knowing how to spot a forgery | 259 | 04:06 | |

| 63. Copies, imitations and attribution | 201 | 02:14 | |

| 64. Exposing forgery in art | 289 | 03:05 | |

| 65. Difficult days at Christie's | 253 | 04:45 | |

| 66. A faked van Dyck causes confusion | 256 | 03:29 | |

| 67. Being ill-used by Christie's | 261 | 05:10 | |

| 68. Why I left Christie's | 288 | 05:36 | |

| 69. Moving from the art market to art criticism | 235 | 02:02 | |

| 70. Speaking out in defense of the truth | 274 | 04:10 |

[Q] So there are forgers who could… who can draw like Goya, say. They can produce… well, they can’t… you told me they can’t produce a Goya, but they can produce a Goya that would fool a lot of people. I mean, they can do…

There are, of course, forgers who fool a lot of people, but it’s a very complicated business, because there are a lot of people who want to be fooled. There are a lot of people who want to discover another Rembrandt drawing. He’s the man who found the Rembrandt drawing, you know. It’s a kind of… if you find a genuine Rembrandt drawing of enormous importance, you become associated with it, and it makes you important, because it is important. It’s the problem with the Dürer in the National Gallery. It’s not by Dürer and we’re all beginning to come round to the fact that it’s not by Dürer. It’s not a forgery, but it’s a mistaken attribution. But the little Madonna of the Pinks, supposedly by Raphael, again in the National Gallery. It’s so exciting to have identified an important early Raphael. All those involved in this discovery and identification are sort of preening themselves with the excitement of it. And then the sceptic comes along and says, 'But where does it fit? You say this is 1504, well, this is what he was doing in 1503'. This is what he was doing in 1505. How does it fit?' You know, they don’t want to know. And then gradually another person comes along and asks the same question. I simply cannot fit this in. And another and another. And ten years have passed, and there’s now a considerable degree of scepticism about that picture.

That’s when it takes time, because so many… if you have enough really eminent people going along with it, happy to be deluded, it’s much more difficult to knock it off its perch. But eventually, it will tumble from its perch, because people who are not involved in the discovery can be very much less… very much more dispassionate about it.

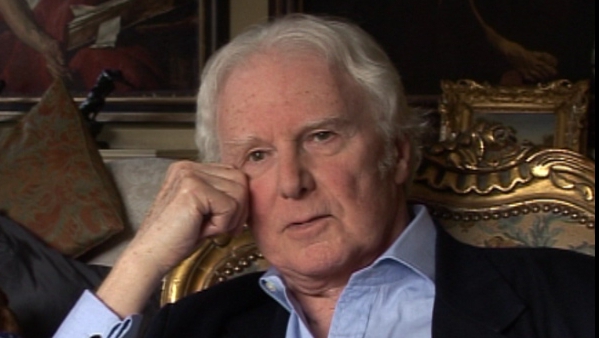

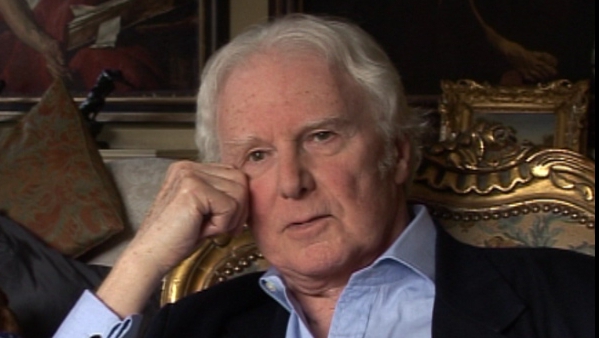

Born in England, Brian Sewell (1931-2015) was considered to be one of Britain’s most prominent and outspoken art critics. He was educated at the Courtauld Institute of Art and subsequently became an art critic for the London Evening Standard; he received numerous awards for his work in journalism. Sewell also presented several television documentaries, including an arts travelogue called The Naked Pilgrim in 2003. He talked candidly about the prejudice he endured because of his sexuality.

Title: Exposing forgery in art

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: National Gallery London, The Madonna of the Pinks, Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino, Raphael, Albrecht Dürer

Duration: 3 minutes, 5 seconds

Date story recorded: April 2013

Date story went live: 04 July 2013