NEXT STORY

Searching for healthy female fetal tissue

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Searching for healthy female fetal tissue

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 121. Frank Perkins | 57 | 02:37 | |

| 122. Human adult cell replication lower than fetal cell replication | 68 | 01:52 | |

| 123. Nathan Shock | 63 | 02:16 | |

| 124. Replacing WI-25 with WI-26 | 67 | 02:48 | |

| 125. Searching for healthy female fetal tissue | 183 | 04:29 | |

| 126. Laying down the first standards for vaccine production | 65 | 05:31 | |

| 127. The global distribution of WI-38 | 224 | 00:56 | |

| 128. The Hayflick limit | 2 | 221 | 02:06 |

| 129. Drago Ikić promotes the use of human cell culture | 73 | 02:11 | |

| 130. Worldwide production of vaccines using the WI-38 cell strain | 136 | 01:40 |

Returning to the events in the laboratory in the early 1960s, I should describe the events that occurred after the freezer failure in which I lost all 25 of the original human... normal human strains that were described. And so, I invented a replacement called WI-26, and because all of the previous strains seemed to have the same properties, that we were interested in at least, one strain was sufficient to develop. And my goal was to lay down in our liquid nitrogen freezer, I think we had by this time, which was more... which was safer and less likely to... to force loss of cell ampoules we develop another strain.

Because the... there was WI-25, the obvious name for the one that I was going to make was WI-26. And that one was a male cell strain, which is important for a reason that will became apparent in a moment. The WI-26 I laid down in several hundred ampoules had early population doublings, maybe sixth or seventh doubling. And this was... that number I thought would supply the world's requirements for an indefinite period of time.

It turned out that I was wrong; that within a very short period of time, the worldwide demand for the cells was such that it was almost immediately apparent in 1961, the beginning of the year I believe, that WI-26 would not last long enough, although it was by then fairly widely distributed. So, we decided to do another cell strain and because WI-26 was male, we decided to make one from a female foetus in order to assure a likely way of distinguishing between the two.

One can make those distinctions on biochemical terms today that could not be made easily at that time. And because we had the Barr bodies in the female cells, not the male cells, that would be an easy way of making a distinction if there was confusion or contamination of one cell culture with another, which was a continuing problem – still is today – in the field of cell culture; that is, contamination of one culture with cells from another.

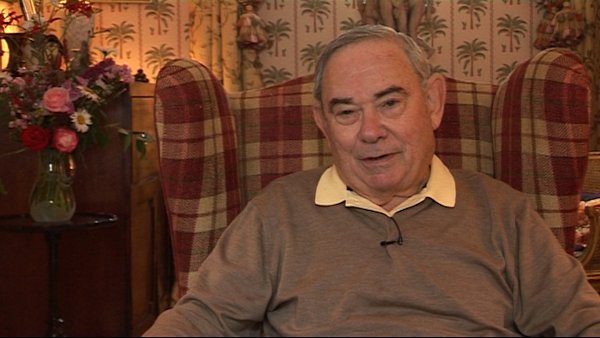

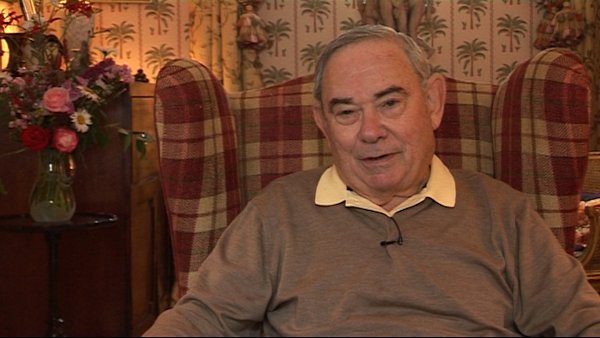

Leonard Hayflick (b. 1928), the recipient of several research prizes and awards, including the 1991 Sandoz Prize for Gerontological Research, is known for his research in cell biology, virus vaccine development, and mycoplasmology. He also has studied the ageing process for more than thirty years. Hayflick is known for discovering that human cells divide for a limited number of times in vitro (refuting the contention by Alexis Carrel that normal body cells are immortal), which is known as the Hayflick limit, as well as developing the first normal human diploid cell strains for studies on human ageing and for research use throughout the world. He also made the first oral polio vaccine produced in a continuously propogated cell strain - work which contributed to significant virus vaccine development.

Title: Replacing WI-25 with WI-26

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: freezer failure, WI-26, liquid nitrogen, male cell strain, female fetus, Bar bodies, contamination

Duration: 2 minutes, 48 seconds

Date story recorded: July 2011

Date story went live: 08 August 2012