NEXT STORY

My first encounter with a computer

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

My first encounter with a computer

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21. A short history of neural networks | 1503 | 02:30 | |

| 22. How I became interested in neural networks | 1 | 1254 | 01:53 |

| 23. My early methods for testing neural networks | 1063 | 02:10 | |

| 24. My PhD thesis on learning machines | 1208 | 01:06 | |

| 25. John Nash solves my PhD problem | 1879 | 01:48 | |

| 26. Why I changed from bottom-up to top-down thinking | 2 | 2583 | 02:39 |

| 27. The end of my PhD on learning machines | 1205 | 04:24 | |

| 28. My first encounter with a computer | 1 | 1028 | 01:56 |

| 29. Writing a program for Russell Kirsch's SEAC | 910 | 01:54 | |

| 30. The first timeshared computer | 879 | 01:03 |

Now, right now, most of the world says: if we understood what neurons do enough, well enough, then we could figure out how thinking works. What I’m saying is, it’s really not so important what the neurons do because they probably... they probably have been rearranged by evolution so that small groups of them, like the columns of 400 or 500 neurons that Mountcastle discovered in the 1950s. What’s probably important is to know what these groups of columns of neurons do, rather than how the neurons themselves work, and to guess what’s important about what they do is very hard unless you have a higher level psychological theory of what kinds of knowledge is needed, and how that knowledge is represented, and how do you acquire it, and how do you decide when to suppress one kind of reasoning and use another, and so forth. So all of this happened to me around 1956 or '57, when I started to say, instead of figuring out how to make a thinking machine from little atoms or cells or something, let’s start from the top level the way Freud did and say: What are the highest functions that we want the machine to have? And what sub-machines would it take to support those and that’s worked out?

And this would be a nice way to divide up the field, because there are several hundred thousand people working on neuroscience in the world, a lot of smart people, and there are only about 20 or less on the whole planet who are thinking about: What are the top levels of cognitive operations that... that thinking might be composed of? So what I would like to see is more support and more people working on these high-level theories, and maybe... a few less of this huge number of people working on theories of what neurons do, and then we would be more likely sooner to meet in the middle, and have a complete theory of how to build a smart machine.

So that’s where my thesis ended, about 1954, and I was converted to saying, let’s try to develop higher-level symbolic reasoning systems. And I wasn’t quite the first to do that, because at Carnegie Mellon Institute... because at Carnegie Mellon Institute there was a pair of... or three researchers, Allen Newell, Herbert Simon and Clifford Shaw, who were working on that very idea of saying: What are the highest level cognitive operations to make a machine that can do reasoning? And for several years I sort of developed my theories in parallel, and adopting some of the ideas that... of Newell, Shaw and Simon. And I had the good fortune that some administrators at the RAND Corporation in Santa Monica were interested in... in this new approach to things, and they had already... they were already supporting Newell and Simon, and they had a... one of the first computers – and we’re talking 1954 or so, there weren’t many computers yet – and so I used to go out there in... in the summers and work on these theories myself, and with mostly Newell and Simon; and that was a very small community.

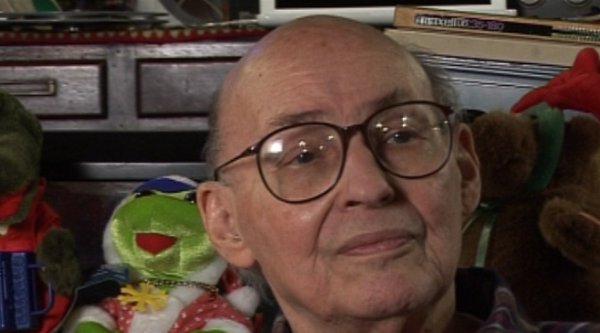

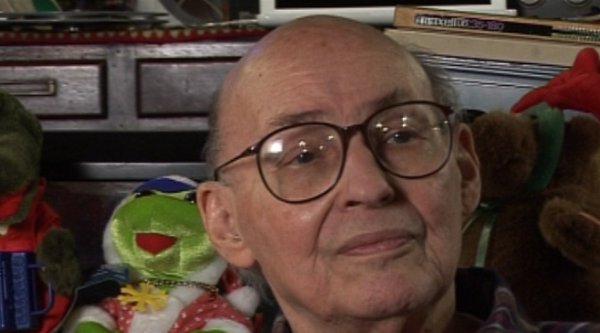

Marvin Minsky (1927-2016) was one of the pioneers of the field of Artificial Intelligence, founding the MIT AI lab in 1970. He also made many contributions to the fields of mathematics, cognitive psychology, robotics, optics and computational linguistics. Since the 1950s, he had been attempting to define and explain human cognition, the ideas of which can be found in his two books, The Emotion Machine and The Society of Mind. His many inventions include the first confocal scanning microscope, the first neural network simulator (SNARC) and the first LOGO 'turtle'.

Title: The end of my PhD on learning machines

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: 1950s, 1954, Carnegie Mellon Institute, Carnegie Mellon University, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Vernon Benjamin Mountcastle, Sigmund Freud, Allen Newell, Herbert Simon, Clifford Shaw

Duration: 4 minutes, 25 seconds

Date story recorded: 29-31 Jan 2011

Date story went live: 09 May 2011