NEXT STORY

Gaining skills in mechanical jobs

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Gaining skills in mechanical jobs

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Did I have a miserable childhood? | 3 | 9738 | 02:51 |

| 2. My early artistic talents | 3219 | 02:09 | |

| 3. First experiences with watches | 3718 | 02:23 | |

| 4. Making an exploding clock | 2686 | 02:28 | |

| 5. Doing battle with a gramophone spring | 2313 | 01:42 | |

| 6. Escape from the bedding factory | 2190 | 02:33 | |

| 7. Gaining skills in mechanical jobs | 2236 | 05:04 | |

| 8. Making money playing the mouth organ | 1860 | 02:36 | |

| 9. Learning to blow up tanks with a mortar | 1 | 1942 | 01:48 |

| 10. Farming while in the army | 1580 | 03:15 |

Then when I got to the age of 14, it was time to leave school and go out to work and, of course, I would have liked to have gone to the watchmaker in Kingsbury, but that wasn't possible because he could only pay seven shillings a week, which is about 30 pence today, and the bedding factory offered 10 shillings a week. And so I spent my days clipping bedsprings together to form the foundation for the company's 'Sleep Easy' mattresses and it was very dull work, dreadfully dull work. And the people who worked there were the crudest sort of labourers and rough and the work was rough and the building was uncongenial, dirty, it really was a sort of slave labour factory, of which a great many existed in London. I'm speaking now of the 1930s.

And so I, not enjoying this work, decided I must get out of it, but the trick was to prevent my mother knowing I was getting out of it because she could see her seven shillings a week going down the drain if I didn't keep this job going. But I had started - when I was about 10 years of age - a firewood business and I would go around the shops and get old wooden cartons and chop them up and hawk them round the houses and get paid like that, and so I knew a lot of people and they were very kindly, generous people and I enjoyed their company and we got on very well. Often they'd have me in for meals and look after me, so all that was very enjoyable. And one of them... I told one of them one day that I was very unhappy about this work business and she very kindly found me a job as an errand boy. Well this was a wonderful opportunity because I was out all day. I had a bicycle that I could take home and use again in the evenings and I got paid for it and there was also a bonus in that job because after I'd been in it for about nine months, the clock stopped and I was paid ten shillings to repair it. So it was a very beneficial occupation for me.

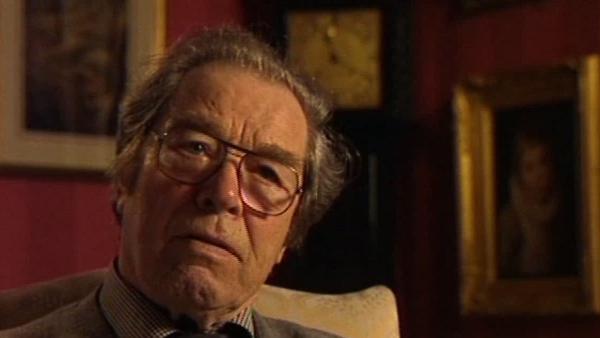

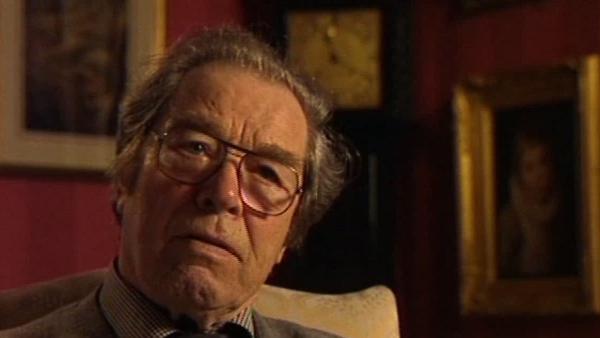

George Daniels, CBE, DSc, FBHI, FSA (19 August 1926 - 21 October 2011) was an English watchmaker most famous for creating the co-axial escapement. Daniels was one of the few modern watchmakers who could create a complete watch by hand, including the case and dial. He was a former Master of the Clockmakers' Company of London and had been awarded their Gold Medal, a rare honour, as well as the Gold Medal of the British Horological Institute, the Gold Medal of the City of London and the Kullberg Medal of the Stockholm Watchmakers’ Guild.

Title: Escape from the bedding factory

Listeners: Roger Smith

Roger Smith was born in 1970 in Bolton, Lancashire. He began training as a watchmaker at the age of 16 at the Manchester School of Horology and in 1989 won the British Horological Institute Bronze Medal. His first hand made watch, made between 1991 and 1998, was inspired by George Daniels' book "Watchmaking" and was created while Smith was working as a self-employed watch repairer and maker. His second was made after he had shown Dr Daniels the first, and in 1998 Daniels invited him to work with him on the creation of the 'Millennium Watches', a series of hand made wrist watches using the Daniels co-axial escapement produced by Omega. Roger Smith now lives and works on the Isle of Man, and is considered the finest watchmaker of his generation.

Tags: Kingsbury, 1930s

Duration: 2 minutes, 34 seconds

Date story recorded: May 2003

Date story went live: 24 January 2008