NEXT STORY

Making money playing the mouth organ

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Making money playing the mouth organ

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Did I have a miserable childhood? | 3 | 9738 | 02:51 |

| 2. My early artistic talents | 3219 | 02:09 | |

| 3. First experiences with watches | 3718 | 02:23 | |

| 4. Making an exploding clock | 2686 | 02:28 | |

| 5. Doing battle with a gramophone spring | 2313 | 01:42 | |

| 6. Escape from the bedding factory | 2190 | 02:33 | |

| 7. Gaining skills in mechanical jobs | 2236 | 05:04 | |

| 8. Making money playing the mouth organ | 1860 | 02:36 | |

| 9. Learning to blow up tanks with a mortar | 1 | 1942 | 01:48 |

| 10. Farming while in the army | 1580 | 03:15 |

I stayed there for a couple of years and it wasn't very constructive, I didn't learn anything there, I just enjoyed myself, but I wanted to do more and I knew where there was a works that interested itself in motorcars and accessories, ancillaries, tyres, batteries, all the things that needed attention on a motorcar. And I was able to persuade the proprietor, a tall rangy American, that I was the chap he wanted in this building and he took me on. Again at 10 shillings a week, so that was a very happy arrangement for me. And there I learnt how to retread tyres.

The war was on and tyres were in short supply and we would retread them, fairly badly I think, but at least they had treads and would run and we were always advising the purchasers not to corner wildly and never to exceed 30 miles an hour because there might be difficulty with the tyres. And they were very happy to do that, very pleased to move about... no other way they could get their cars maintained on the road. And we did the same with the batteries... repaired the batteries. In those days, of course, everything came up for repair. Nowadays, if the battery goes flat, a man goes out and buys another battery, but in those days you had the battery repaired and you'd save. If a battery were a pound, then you would repair it for five shillings and save 15 shillings. And it's extraordinary how many things carried an extra sixpence. Everything was so many shillings and sixpence, and the sixpences you see were not very significant to the purchaser, but they added up at the end of the day. Sometimes one would spend two hours repairing a motorcar tyre and I mean it would be grossly uneconomical today, but in those days if you spent two hours on that and you charged the man five bob, he is very happy, he's got his car back on the road for five bob and we're very happy we've got the five bob. And otherwise it would have just been thrown away. But they were very lean days. Nothing was thrown away without it being repaired to the point of exhaustion. You couldn't do any more with it and then it could be discarded.

I stayed in that job for a couple of years and during that time we took an interest in the entertainment business. My boss had taken an interest in cinematographs and he had a cinematograph machine and some films and he decided that he would go into making these things for sale to the public. There was a war on and the cinemas were closed, theatres were closed. Only those with a radio or some home entertainment could get any pleasure out of the arts and the sciences - they just weren't available in those days. And so we started to make these machines and we became very adept at it and there were several different sized films in those days. It was all very confusing because there was a great deal of competition between different manufacturers... Kodak and Pathé and Western Electric all had their own systems and so we were forever finding ways of turning this machine into what was that machine and vice versa. And so it was very constructive and interesting and I learnt a lot there, and in particular, I learnt about electricity, how to use it on these things and the amplifiers for the sound.

And then I felt that I ought to advance this knowledge of electricity and so I left that job and I went to another firm in North London, Franco-British Electric, and I took a job there and to my astonishment, they paid me £2 a week. It was quite extraordinary that I should jump from this small amount, 10 bob up to £2. And I found I was getting the money for nothing because I wasn't doing anything and I wasn't trusted to do anything. I wasn't considered to be able to know anything and the trade unions wouldn't let me do anything because that would be taking work away from a mature member of the trade union. So it was all terribly restrictive and mealy-mouthed and mingy, and I didn't really learn anything there. Soon I was 18 and then, of course, I was directed into the army.

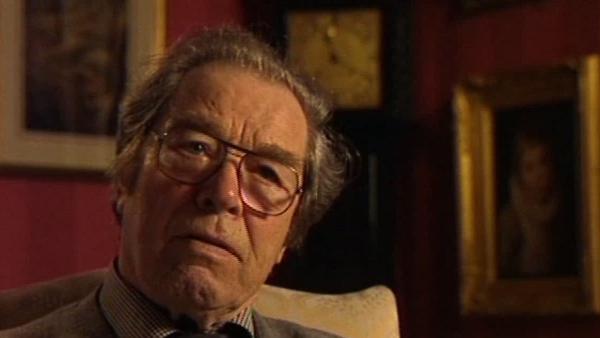

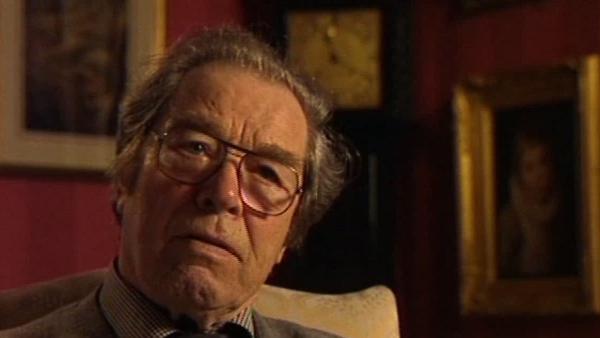

George Daniels, CBE, DSc, FBHI, FSA (19 August 1926 - 21 October 2011) was an English watchmaker most famous for creating the co-axial escapement. Daniels was one of the few modern watchmakers who could create a complete watch by hand, including the case and dial. He was a former Master of the Clockmakers' Company of London and had been awarded their Gold Medal, a rare honour, as well as the Gold Medal of the British Horological Institute, the Gold Medal of the City of London and the Kullberg Medal of the Stockholm Watchmakers’ Guild.

Title: Gaining skills in mechanical jobs

Listeners: Roger Smith

Roger Smith was born in 1970 in Bolton, Lancashire. He began training as a watchmaker at the age of 16 at the Manchester School of Horology and in 1989 won the British Horological Institute Bronze Medal. His first hand made watch, made between 1991 and 1998, was inspired by George Daniels' book "Watchmaking" and was created while Smith was working as a self-employed watch repairer and maker. His second was made after he had shown Dr Daniels the first, and in 1998 Daniels invited him to work with him on the creation of the 'Millennium Watches', a series of hand made wrist watches using the Daniels co-axial escapement produced by Omega. Roger Smith now lives and works on the Isle of Man, and is considered the finest watchmaker of his generation.

Tags: World War II, Kodak, Pathé, Western Electric, London, Franco-British Electrical Co, British Army, cinematograph

Duration: 5 minutes, 5 seconds

Date story recorded: May 2003

Date story went live: 24 January 2008