NEXT STORY

The Lamb shift

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The Lamb shift

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 61. Fellow graduate students at Cornell | 1866 | 02:26 | |

| 62. Social differences between England and the US | 2016 | 01:11 | |

| 63. The Cold War and the Federation of American Scientists | 1585 | 02:26 | |

| 64. The Lamb shift | 1 | 3217 | 05:44 |

| 65. Hans Bethe | 1 | 2749 | 04:57 |

| 66. The difficulty of getting anything started | 1 | 1904 | 00:46 |

| 67. Working practice | 3 | 1783 | 01:51 |

| 68. Moving from Cornell to the Institute for Advanced Study | 1698 | 01:54 | |

| 69. Julian Schwinger's summer school talks | 2892 | 00:42 | |

| 70. An educational road trip with Richard Feynman | 3421 | 02:35 |

It all started sort of when I was in Cornell. I think the Truman Doctrine was that summer, but the Cold War hadn't really got going in a way that affected us much. I don't remember the chronology, but certainly I was deeply involved with the Federation of American Scientists - Phil Morrison was one of their leading people and Hans Bethe was also. I mean that this was a very serious concern; this was fighting for civilian control of nuclear weapons and for the international... civilian control of the atomic energy industry in the United States, and international control of the weapons. So there was a great deal of political activity going on. I became a member of the Federation already at that point, and so we used to go to Federation meetings and learn about all the things that were going on at the United Nations and Washington. The United Nations Atomic Energy Commission was having its meetings, I think, at that time.

[Q] And this was your first meeting with Kramers, or you didn't meet Kramers at that stage?

Not until... I met him at Princeton, but he was of course the Netherlands delegate to that. But already at Cornell, that, I think, that was the political activity I was mostly engaged in. It wasn't the Cold War at that point.

[Q] It was still international control over atomic energy.

Yes, and trying to get, almost, world government. I mean trying to get people to take the United Nations seriously.

[Q] And Cornell was interesting in that sense because you had Wilson and Bethe and Morrison and....

They all talked about Los Alamos, and so we used to sit at lunch and hear stories about Los Alamos, so that to me was also another new world, and it was something that I had not heard about at all in England. In England there were of course a few people who came back from Los Alamos but they were not talking about it to that extent.

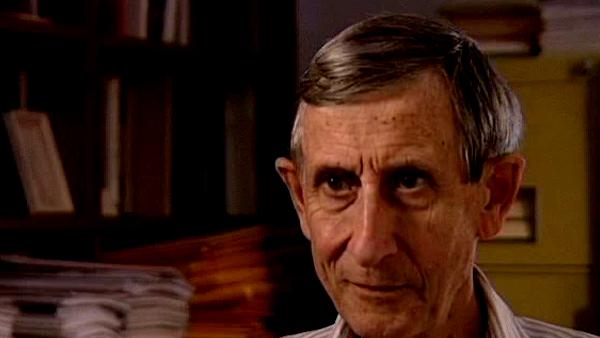

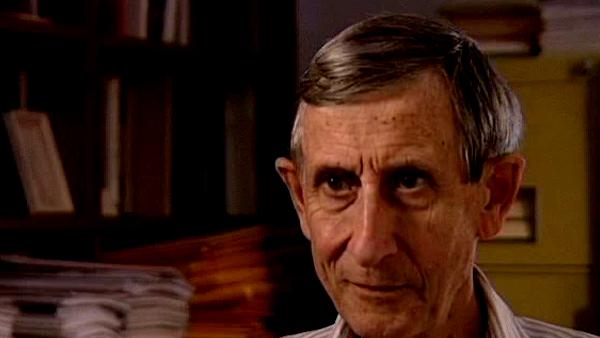

Freeman Dyson (1923-2020), who was born in England, moved to Cornell University after graduating from Cambridge University with a BA in Mathematics. He subsequently became a professor and worked on nuclear reactors, solid state physics, ferromagnetism, astrophysics and biology. He published several books and, among other honours, was awarded the Heineman Prize and the Royal Society's Hughes Medal.

Title: The Cold War and the Federation of American Scientists

Listeners: Sam Schweber

Silvan Sam Schweber is the Koret Professor of the History of Ideas and Professor of Physics at Brandeis University, and a Faculty Associate in the Department of the History of Science at Harvard University. He is the author of a history of the development of quantum electro mechanics, "QED and the men who made it", and has recently completed a biography of Hans Bethe and the history of nuclear weapons development, "In the Shadow of the Bomb: Oppenheimer, Bethe, and the Moral Responsibility of the Scientist" (Princeton University Press, 2000).

Tags: Cornell University, Truman Doctrine, Cold War, Federation of American Scientists, USA, United Nations, UN, Washington, United Nations Atomic Energy Commission, Princeton University, Netherlands, Holland, Los Alamos, UK, Philip Morrison, Hans Bethe, Hans Kramers, Robert Wilson

Duration: 2 minutes, 27 seconds

Date story recorded: June 1998

Date story went live: 24 January 2008