Why is it that we haven't, in documentary form, that is, as pieces of non fiction audiovisual, filmed what could be called poems? And the obvious thing is, I suppose, to film a poet reading his poetry, but that's not what I mean. I mean something that is an audiovisual document- documentary- that, that is a poem in itself, like the man chasing the butterflies. Or: I remember standing and waiting for a bus and the bus didn't seem to be coming so I got out onto the street, looked all the way down the street; nothing coming. So I came back to the kerb to find that another person who was waiting for the bus- this older woman- who put her hand on my shoulder and said- don't worry, the bus'll come soon. And right away we were talking with each other but I wasn't saying anything because her story was so interesting. It was a story that, in those few moments, gave away her whole life story, or at least the most important thing in her life. She said, first of all- she said- she said- I'm getting into my, my 90s and somehow- maybe because of the way I looked at her, maybe because she felt that I was empathizing with her, she suddenly said- you know, I had this wonderful sister of mine and she, she- I never got married so I never had any children and she never got married so nei- she never had any children, but we had each other. And two years ago, she said, she died and it has left me devastated. That was almost enough in itself. But then as we got on the bus she turned to me and to finish the poem- and she said- you know, we loved each other so much that I don't think any man would want to come between us. And that was a poem, I would say. Another piece of poetry in film form- in documentary film form, so it's a spontaneous thing without any control- I'm looking at a very much overweight black woman on the bus, and she's just looking off into the- into the blue. Nothing's going on. But it's something about- I don't know- I felt maybe that something was going to happen. But anyway, I nudged the woman next to me and now the two of us were looking at this woman, but very kindly, so that she wasn't affected by it. She just kept looking off into the distance. At that moment the little girl next to her, also black, maybe eight or nine years old- had to be her daughter- gets up, slips around in front of her mother, and nestles her head between her mother's enormous breasts, which would seem to be enough except this little girl then fell asleep. Well, from nothing- from even something negative in the mind of, of people with the stereotype of, of a fat lady, right, who was black, right, has turned out to be a very universal thing of motherhood. It was almost as though some super power had come down to change everything, to make it more beautiful. But that wasn't necessary. There was something between those two people that provided that beauty for me, had I had the camera, and for this woman, because I had noticed it. Then there's another story, which I think could have been a poem had I filmed it. I better get into making these poems. I got to have a camera with me all the time so I can catch these things as they happen. This one would've been very easy to do, and you'll see why. I noticed across the aisle from me on that same bus on another occasion an older man was talking to a woman- I think they probably just met a couple of stops before- and he was telling her how it's so true that when he was in the war it was always young kids and they're the ones get killed. And starting off with that serious story he, he got to be looking at me. And he was sharing his storytelling with her and me but looking at me very intensely and saying, saying, at one point- you know, here it is, it's nine o'clock in the morning; I get up at eight thirty every morning; I have a, a full day's activities and I- And then, still looking at me intensely, he says- I'm 86 years old and I'm totally blind. Oh, my God. So, anyway, had I filmed it I'd have a title for that one: Sight Unseen. So it goes on. I don't know. I think that what I'd like to do is- when I have the time for it- is to really just spend a day with my camera and, as a still photographer might do, search out that moment; in this case, that poem. And if I- if it takes too long for me to make a collection of all these for a half-an-hour, an hour show, I, I would be most eager, as some people do when they come forth with their poetry, to make it a collection where there are other people- other, other young filmmakers- that- some of them who are interning in my office- I'd let them have a go at it. In fact I've spoken to them about it and I'm eager for them get started.

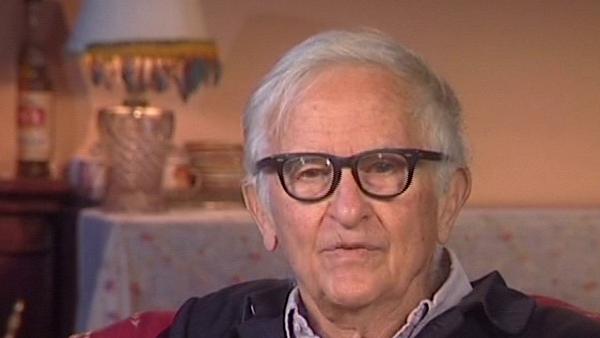

Albert Maysles (1926-2015) known for his important documentaries on Muhammad Ali, Jimi Hendrix and The Beatles, pioneered the documentary style known as Direct Cinema. He helped create techniques still widely used in modern documentary production, as well as many of the techniques used in reality TV.

Title: Examples of audiovisual poetry

Listeners:

Rebekah Maysles

Sara Maysles

Tamara Tracz

Rebekah Maysles, daughter of Albert Maysles, is an artist living between New York and Philadelphia. She has her own line of clothing, Blackberryrose, and co-runs the store Sodafine in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, New York, a vintage and handmade store that sells clothing, books and other products made by artists.

Sara Maysles, daughter of Albert Maysles, is currently doing her BA in East Asian Studies at Columbia University, and working as an Archivist of the photographs and photographic material at Maysles Films Inc., Albert‚s film production company. She spent ten months out of two years working with Tibetan refugees at a center in Nepal, and continues to travel back and forth between America and Asia.

Tamara Tracz is a writer and filmmaker based in London.

Tags:

poetry, documentary, film

Duration:

6 minutes, 55 seconds

Date story recorded:

September 2004

Date story went live:

29 September 2010