NEXT STORY

A visit by Kimura whilst teaching at Berkeley

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

A visit by Kimura whilst teaching at Berkeley

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 81. Two theories on sexual inequality | 662 | 04:47 | |

| 82. The essential difference between male and female gametes | 606 | 02:11 | |

| 83. Experiencing feminism in science | 741 | 01:59 | |

| 84. Kimura and King: Neutral theory of molecular evolution | 1274 | 02:54 | |

| 85. A visit by Kimura whilst teaching at Berkeley | 657 | 01:58 | |

| 86. Inspiring Kimura to write The Neutral Theory of Molecular... | 715 | 03:09 | |

| 87. Molecular clocks | 661 | 02:37 | |

| 88. Major transitions in evolution | 687 | 02:52 | |

| 89. Examples of major transitions in evolution | 563 | 03:35 | |

| 90. The evolution of language | 872 | 05:17 |

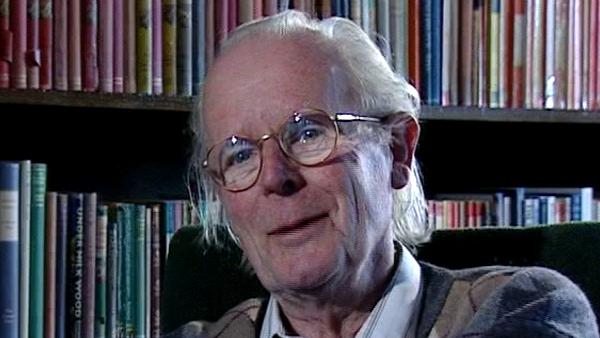

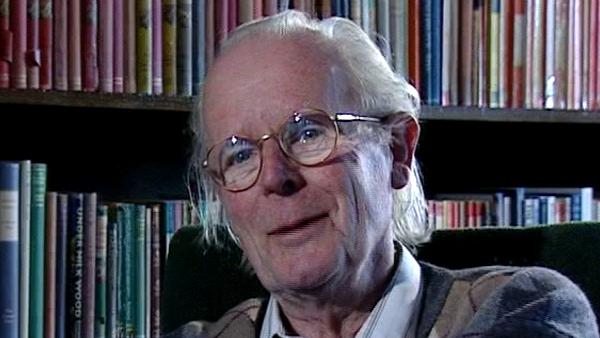

I had a slightly curious position on that when the serious debates were going on. I mean, when Kimura's paper was published... Kimura and King, it's - one's so bad at dates, 1961, could it be? - anyway, whenever, when it was first published, this led, particularly in Britain, to deep hostility to the notion that anything could be selectively neutral. The whole tradition of British population biology had been if you find a genetic variability, it must have some kind of selective explanation, and if at first you don't find it, you must try, try and try again, until you do. And the suggestion that there were genetic changes out there which were selectively neutral, was really deeply distasteful to these people. And there was really quite an extraordinary level of debate on the issue. Which... and what seemed to me so strange at the time, that people felt they had to take sides. I remember, it was at its height at a period when Dick Lewontin spent a year in my lab here. And I remember we talked about it and we both agreed that at the moment we couldn't see anything really decisive, one way or the other. And we kept on trying to think of decisive statistical measures or experiments one could carry out, to decide whether the neutral theory was true. And we kept on coming up with ideas and then deciding that they wouldn't really settle the issue, because, you know. And so we both agreed the only sensible thing was to do was to say we don't know, it didn't seem to be necessary in science to say you know when you don't. But almost everybody else seemed to take rigorous sides. I think that the... this degree of polarity has disappeared, and I think today most people who've thought about the matter seriously, really see the value of the neutral theory as a kind of null hypothesis. The great beauty of the neutral theory is it says, there is no selection. It is then possible to work out, in great detail, what you expect to happen, and what you expect to happen to distribution of gene frequencies, their rates of change in time, and all sorts of things of that kind. Once you start saying there's selection, anything goes, because you don't know what the selection is, you can't predict anything. And so the neutral theory provides one with a really admirable sort of null hypothesis against a background to which you can... you can pick out the cases where clearly it's not neutral, and you can say, 'That's selective because it doesn't agree with the neutral hypothesis.' So, I've no doubt at all that Kimura's contribution was profound and really has changed population genetics.

The late British biologist John Maynard Smith (1920-2004) is famous for applying game theory to the study of natural selection. At Eton College, inspired by the work of old Etonian JBS Haldane, Maynard Smith developed an interest in Darwinian evolutionary theory and mathematics. Then he entered University College London (UCL) to study fruit fly genetics under Haldane. In 1973 Maynard Smith formalised a central concept in game theory called the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS). His ideas, presented in books such as 'Evolution and the Theory of Games', were enormously influential and led to a more rigorous scientific analysis and understanding of interactions between living things.

Title: Kimura and King: Neutral theory of molecular evolution

Listeners: Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins was educated at Oxford University and has taught zoology at the universities of California and Oxford. He is a fellow of New College, Oxford and the Charles Simonyi Professor of the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University. Dawkins is one of the leading thinkers in modern evolutionary biology. He is also one of the best read and most popular writers on the subject: his books about evolution and science include "The Selfish Gene", "The Extended Phenotype", "The Blind Watchmaker", "River Out of Eden", "Climbing Mount Improbable", and most recently, "Unweaving the Rainbow".

Tags: Motoo Kimura, JC King, Richard Lewontin

Duration: 2 minutes, 55 seconds

Date story recorded: April 1997

Date story went live: 24 January 2008