NEXT STORY

Inspiring Kimura to write The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Inspiring Kimura to write The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 81. Two theories on sexual inequality | 662 | 04:47 | |

| 82. The essential difference between male and female gametes | 606 | 02:11 | |

| 83. Experiencing feminism in science | 741 | 01:59 | |

| 84. Kimura and King: Neutral theory of molecular evolution | 1274 | 02:54 | |

| 85. A visit by Kimura whilst teaching at Berkeley | 657 | 01:58 | |

| 86. Inspiring Kimura to write The Neutral Theory of Molecular... | 715 | 03:09 | |

| 87. Molecular clocks | 661 | 02:37 | |

| 88. Major transitions in evolution | 687 | 02:52 | |

| 89. Examples of major transitions in evolution | 563 | 03:35 | |

| 90. The evolution of language | 872 | 05:17 |

I was in Berkeley for a semester, and I was teaching a group of graduate students a course in theoretical biology. It was a lovely teaching job, I know many of them still and they were great students, lovely. And while I was running this seminar, Kimura came through and gave a seminar. And I asked him if he would spend the evening with my class, and just talk, we would talk with him and so on. And it was a fascinating evening, I'd love to have it on tape, except you should never tape something without the person present knowing, I mean, I wouldn't have dreamed of taping it, but all the same, I'd love to have a tape of that evening. Because these kids were very nice and, on the whole, very bright, but they were also, being Americans, rather brash and they... they were quite willing to press this great man and not let him get away from it, and so he was really pushed into discussing issues which are normally very hard for him. And the one thing I remember of the evening, actually what he said, was actually in answer to a question I asked him. I said, 'Look, Motoo, there are really two parts to the neutral theory. The neutral theory first of all says that selective... not selective, that changes in molecules that occur, or mostly occur, because they're selectively neutral. And the other one says that the... if you look at the standing crop of variation at any one time, most of that variation is neutral. Now, it's logically possible that one of those statements is right and the other one is wrong. How would you feel if it turned out that you were right about substitution but wrong about polymorphism?' And he said, 'It is logically possible, but it would be very inelegant.' And I think this tells you about Kimura's mind. It was a mind which liked elegance. It was a very powerful mind but it was a mind which was seeking for simplicity.

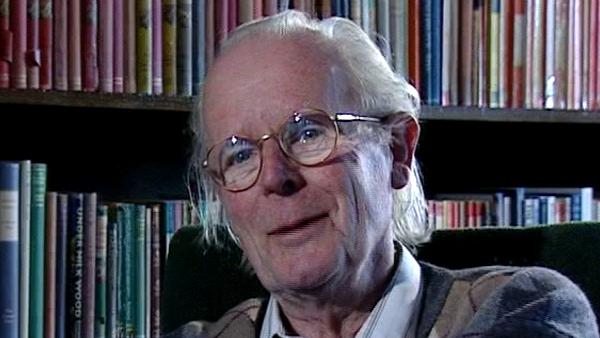

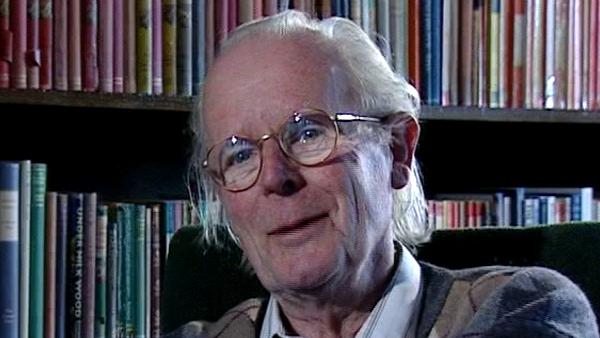

The late British biologist John Maynard Smith (1920-2004) is famous for applying game theory to the study of natural selection. At Eton College, inspired by the work of old Etonian JBS Haldane, Maynard Smith developed an interest in Darwinian evolutionary theory and mathematics. Then he entered University College London (UCL) to study fruit fly genetics under Haldane. In 1973 Maynard Smith formalised a central concept in game theory called the evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS). His ideas, presented in books such as 'Evolution and the Theory of Games', were enormously influential and led to a more rigorous scientific analysis and understanding of interactions between living things.

Title: A visit by Kimura whilst teaching at Berkeley

Listeners: Richard Dawkins

Richard Dawkins was educated at Oxford University and has taught zoology at the universities of California and Oxford. He is a fellow of New College, Oxford and the Charles Simonyi Professor of the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University. Dawkins is one of the leading thinkers in modern evolutionary biology. He is also one of the best read and most popular writers on the subject: his books about evolution and science include "The Selfish Gene", "The Extended Phenotype", "The Blind Watchmaker", "River Out of Eden", "Climbing Mount Improbable", and most recently, "Unweaving the Rainbow".

Tags: Berkeley, USA, Motoo Kimura

Duration: 1 minute, 59 seconds

Date story recorded: April 1997

Date story went live: 24 January 2008